(Original video created and directed by Colin Davis)

With Thanksgiving around the corner, cutouts of Pilgrims in black clothes and clunky shoes are sprouting all over the place. You may know that the Pilgrims sailed aboard the Mayflower and arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620. But did you know their first Thanksgiving celebration lasted three whole days? What else do you know about these early settlers of America? Don’t be a turkey. Try this True-False quiz.

True or False? (Answers below)

The site of Plimouth Patuxet Plantation is definitely worth a visit.

Answers

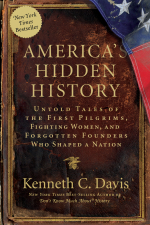

Read about America’s real “first Pilgrims”–French Huguenots who landed in Florida more than fifty years before the Mayflower sailed– in this New York Times Op-Ed, “A French Connection“ and in my book America’s Hidden History

The official Juneteenth Committee in East Woods Park, Austin, Texas on June 19, 1900. (Courtesy Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

[Repost of 2014 post]

Happy Juneteenth! Since 1865, June 19th has served as another kind of Independence Day. It is a day that celebrates the end of slavery in America.

On June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger informed former slaves in the area from the Gulf of Mexico to Galveston, Texas that they were free. Abraham Lincoln had officially issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, but it had taken two more years of Union victories to end the war in April 1865 and for this news to reach enslaved people in remote sections of the country.

This is from General Granger’s Order No. 3:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Many of the newly freed slaves in the territory, the last area to receive news of the war’s end and Emancipation, celebrated the news with ecstasy, and according to the Texas State Library, the words “June” and “nineteenth” became a new word and a new celebration of freedom. They called it Juneteenth.

In many parts of Texas, ex-slaves purchased land, or “emancipation grounds,” for the Juneteenth gathering. Examples include: Emancipation Park in Houston, purchased in 1872; what is now Booker T. Washington Park in Mexia; and Emancipation park in East Austin.

Other former slaves began to travel to other states in search of family members who had been separated from them by slave sales. Starting in 1866, that spontaneous celebration –more commonly called “Juneteenth”– spread to become a holiday celebrating emancipation in many parts of the United States, although it still lacks national recognition. Read more about Juneteenth in the article Juneteenth: Our Other Independence Day , which I wrote for Smithsonian.com

Kenneth C. Davis talked about his book, The Hidden History of America at War, about the challenges the U.S. military faced from the Revolutionary War to the War in Iraq. Mr. Davis also argued that there are many popular misconceptions about the American Revolution, and the Civil and Vietnam Wars.

Kenneth C. Davis talked about his book, The Hidden History of America at War: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah. He spoke with Mark Jacob, author of 10 Things You Might Not Know About Nearly Everything.

“Don’t Know About History” took place in the north auditorium of Jones College Prep High School at the 2015 Chicago Tribune Printers Row Lit Fest.

The program concluded with scenes of the book festival and schedule information.

Author Kenneth Davis talked about his body of work and his newest book, Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents. He answered questions from viewers via telephone and electronic communications. Mr. Davis was also the author of eight other books in the Don’t Know Much About… series as well as the book, America’s Hidden History.

Kenneth Davis, author of America’s Hidden History: Untold Tales of the First Pilgrims, Fighting Women, and Forgotten Founders Who Shaped a Nation (Collins; April 29, 2008), talked about his book at the 2008 National Press Club Book Fair.

It’s that time of year. Time once again to explain that the upcoming national holiday is not “Presidents Day.”

Yes, I cannot tell a lie. The day we celebrate on the third Monday in February is really called “George Washington’s Birthday.” Ask the National Archives.

Want to learn a little more?

Here is the website for the National Park Service’s Birthplace of Washington site.

And here is the National Park Service website for Fort Necessity, scene of Washington’s surrender and “confession.”

(Repost of a 2011 videoblog, directed, edited and produced by Colin Davis)

Answer: Labor Day was signed into law by Grover Cleveland in 1894

The end of summer, a three-day weekend, burgers on the grill, and a back-to-school shopping spree, right? And the most important question, “Can I still wear white?”

But very few people associate Labor Day with a turbulent time in American History. That’s what Labor Day is really about. The holiday was born during the violent union-busting days of the late 19th century, when sweat shop conditions killed children, when there was no minimum wage and when going on vacation meant you were out of work.

If you like holidays, benefits and a five-day, 40-hour work week, you need to know about Labor Day.

When Labor Day was signed into law by Grover Cleveland in 1894, it was a bone tossed to the labor movement. And it was deliberately placed in September to ensure that it would not recall the memory of the deadly rioting at Chicago’s Haymarket Square in May 1886. Europe’s workers, and later the Communist Party, adopted May Day as a worker’s holiday to commemorate the deadly Haymarket Sqaure Riot which came about during a strike against thee McCormack Reaper Company.

Although Labor Day did become federal law in 1894, most of labor’s successes –the minimum wage, overtime, the end of child labor – did not come about until the Depression-era reforms of the New Deal.

Labor Day was created to celebrate the “strength and spirit of the American worker.” But this holiday should remind us that — like so many things we take for granted — those victories for working people came at great cost, in blood, sweat and tears.

For more on the history of Haymarket Square, here is a link to the Chicago Historical Society’s web project.

“American Experience,” the PBS documentary series, produced a Homestead Strike piece as part of its film about Andrew Carnegie.

You can read more about the history of the trade union movement in Don’t Know Much About History: Anniversary Edition and Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents.

This video is a brief introduction to my new book, THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah (published May 5, 2015 by Hachette Books and Random House Audio)

“His searing analyses and ability to see the forest as well as the trees make for an absorbing and infuriating read as he highlights the strategic missteps, bad decisions, needless loss of life, horrific war crimes, and political hubris that often accompany war.”

–Publishers Weekly *Starred Review Link Full Review

The Hidden History of America At War-May 5, 2015 (Hachette Books/Random House Audio)

More Advance Praise for THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR

“There’s only one person who can top Kenneth C. Davis—and that’s Kenneth C. Davis. With The Hidden History of America at War, he’s composed yet another brilliant, thought-provoking, and compelling book. . . Davis offers a hard-hitting and sometimes critical look at some of the most consequential wartime decisions made by presidents and policy makers, but his admiration and respect for the men and women who have served and sacrificed so much for this nation is unwavering.”

—Andrew Carroll, editor of the New York Times-bestsellers War Letters and Behind the Lines

“With his trademark storytelling flair, Kenneth C. Davis illuminates six critical, but often overlooked battles that helped define America’s character and its evolving response to conflict. This fascinating and strikingly insightful book is a must-read for anyone who wants to better understand our nation’s bloody history of war.”

—Eric Jay Dolin, author of Leviathan and When America First Met China

“A fascinating exploration of war and the myths of war. Kenneth C. Davis shows how interesting the truth can be.”

—Evan Thomas, New York Times-bestselling author of Sea of Thunder and John Paul Jones

(A repost of a video made a few years ago but always timely. Filmed, directed and edited by Colin Davis)

In June 1812, Congress declared war on Great Britain. It would be derided as “Mr. Madison’s War.”

It is also appropriate to note that today — June 14– is Flag Day, the day that the Continental Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes as the nation’s flag in 1777.

These two landmarks come together because it was during the War of 1812 that America got the words that eventually became its national anthem –with music borrowed from an old English drinking song. Almost from the outset, the song has been butchered at baseball games and Super Bowls.

At war with England for the second time since 1776, the United States was ill-prepared for fighting and the British were preoccupied with a war with France. So it was a fitful few years of war.

But the conflict produced an iconic American moment in September 1814. Francis Scott Key was an attorney attempting to negotiate the return of a civilian prisoner held by the British who had just burned Washington DC and had set their sights on Baltimore. As the British attacked the city, Key watched the naval bombardment from a ship in Baltimore’s harbor. In the morning, he could see that the Stars and Stripes still flew over Fort McHenry. Inspired, he wrote the lyrics that we all know –well, at least some of you probably know some of them.

But here’s what they didn’t tell you:

Yes, Washington, D.C. was burned by the British in 1814, including the President’s Mansion which would be rebuilt and later come to be called the “White House.” But Washington was torched in retaliation for the burning of York –now Toronto—in Canada earlier in the war.

Yes, Key wrote words. But the music comes from an old English drinking song. Good thing it wasn’t 99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall. Here’s a link to the original lyrics of the drinking song To Anacreon in Heaven (via Poem of the Week).

The Star Spangled Banner did not become the national anthem until 1916 when President Wilson declared it by Executive Order. But that didn’t really count. In 1931, it became the National Anthem by Congressional resolution signed by President Herbert Hoover.,

Now here are two other key –no pun intended– events related to Flag Day, June 14:

•In 1943, the Supreme Court ruled that schoolchildren could not be compelled to salute the flag if it conflicted with their religious beliefs

•In 1954 on Flag Day, President Eisenhower signed the law that added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance.

Learn more about Fort McHenry, Key and the Flag that inspired the National Anthem from the National Park Service.

The images and music in this video are courtesy of the Smithsonian Museum of American History which has excellent resources on the flag that inspired Key.

This version of the anthem is on 19th century instruments:

http://americanhistory.si.edu/starspangledbanner/mp3/song.ssb.dsl.mp3

(This is a revised version of a post that originally appeared on March 17, 2012)

It is the day for the “wearing of the green,” parades and an unfortunate connection between being Irish and imbibing. For the day, everybody feels “a little Irish.”

But it was not always a happy go lucky virtue to be Irish in America. Once upon a time, the Irish –and specifically Irish Catholics– were vilified by the majority in White Anglo-Saxon Protestant America. The Irish were considered the dregs by “Nativist” Americans who leveled at Irish immigrants all of the insults and charges typically aimed at every hated immigrant group: they were lazy, uneducated, dirty, disease-ridden, a criminal class who stole jobs from Americans. And dangerous. The Irish were said to be plotting to overturn the U.S. government and install the Pope in a new Vatican.

One notorious chapter in the hidden history of Irish-Americans is left out of most textbook– the violently anti-Catholic, anti-Irish “Bible Riots” of 1844.

In May 1844, Philadelphia –the City of Brotherly Love– was torn apart by a series of bloody riots. Known as the “Bible Riots,” they grew out of the vicious anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiment that was so widespread in 19th century America. Families were burned out of their homes. Churches were destroyed. And more than two dozen people died in one of the worst urban riots in American History.

You can read more about America’s history of intolerance –religious and otherwise– in this Smithsonian essay, “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance.”

On November 4, 2012, New York Times Bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis sat down for a comprehensive three-hour interview with C-Span’s Book TV.

The interview, which included questions from callers and via e-mail, covered Davis’ career as a writer spanning more than 20 years. In the interview, he discussed his approach to writing history in such books as Don’t Know Much About® History. He also described his background, growing up in Mt. Vernon, New York, how he became a writer, and his early work, including his first book, Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America, which discussed the rise of the paperback publishing industry and the impact of books on American society.

Davis also described the success of his “Don’t Know Much About®” series, with its emphasis on making history both accessible and entertaining while connecting the past to the present.

“Eli Whitney,” portrait of the inventor, oil on canvas, by the American painter Samuel F. B. Morse. 35 7/8 in. x 27 3/4 in. Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To mark the birthday of American Eli Whitney on December 8, 1765, here is a short video about the Connecticut-born inventor’s most famous “invention,” the Cotton Gin. This was created as my first contribution to Ted-Ed: “Lessons Worth Sharing.”

This portrait of the inventor is by another inventor– Samuel F.B. Morse who was a well-known painter and art teacher before he gained fame for the development of the telegraph and the Morse Code.

The cotton gin changed history for good and bad. By allowing one field hand to do the work of 10, it powered a new industry that brought wealth and power to the American South — but, tragically, it also multiplied and prolonged the use of slave labor. In this video, I discuss innovation, while warning of unintended consequences.

Eli Whitney died in New Haven, Connecticut on January 8, 1825. You can learn more about Whitney and his inventions at the Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop.