Imacon Color Scanner

(March 15, 2024: Revision of original post of March 15, 2014. Video created and directed by Colin Davis.)

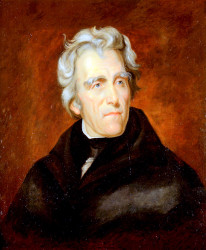

Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States, was born on March 15, 1767.

His birthplace was a cabin on the border of both South and North Carolina (the precise location is uncertain).

When this was last posted, he had fallen from favor and was going to be moved to the back side of the $20 in favor of Harriet Tubman. That decision was shelved by the previous administration and in 2021 was put back on track under the Biden administration.

In his day and ever since, Andrew Jackson provoked high emotions and sharp opinions. Thomas Jefferson once called him, “A dangerous man.”

His predecessor as president, John Quincy Adams, a bitter political rival, said Jackson was,

“A barbarian who could not even write a sentence of grammar and could hardly spell his own name.”

His place and reputation as an Indian fighter began with a somewhat overlooked fight against the Creek nation led by a half-Creek, half-Scot warrior named William Weatherford, or Red Eagle following an attack on an outpost known as Fort Mims north of Mobile, Alabama.

The video above (created in 2014) offers a quick overview of Weatherford’s war with Jackson that ultimately led the demise of the Creek nation.Like Pearl Harbor or 9/11, it was an event that shocked the nation. Soon, Red Eagle and his Creek warriors were at war with Andrew Jackson, the Nashville lawyer turned politician, who had no love for the British or Native Americans.

On March 27, 1814, Jackson’s troops defeated Red Eagle and his Creek warriors, killing more than 800 Natives–women, children, and the elderly as well as warriors. Jackson’s soldiers cut off the noses of the dead to tally their numbers. Other soldiers cut off strips of skin to make reins for their horses. (A Nation Rising, page 66-68)

On August 9, 1814, Major General Andrew Jackson signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson ending the Creek War. The agreement provided for the surrender of twenty-three million acres of Creek land to the United States. This vast territory encompassed more than half of present-day Alabama and part of southern Georgia.

Resources from Library of Congress.

The complete story of the Red Creek War is told in my book A Nation Rising.

Andrew Jackson died on June 8, 1845. He was surrounded by many of the household servants he had enslaved. He told them:

Tombstone of Alfred Jackson, enslaved servant of Andrew Jackson. (Author photo © 2010)

“I want all to prepare to meet me in heaven….Christ has no respect to color.”

The story of one of those people, Alfred Jackson, is told in my recent book, In the Shadow of Liberty. Alfred Jackson is buried in the garden at the Hermitage, near Andrew Jackson’s gravesite.

[Updated March 26, 2023; Originally published August 2009; video edited and created by Colin Davis. One correction: I no longer have a home in Vermont mentioned in the video, but have not lost my admiration for Robert Frost.]

America’s Poet, Robert Frost, was born on March 26, 1874 –not in New England where so many of his greatest poems are set but in San Francisco.

The first poet invited to speak at a Presidential inaugural, Frost told the new President:

Be more Irish than Harvard. Poetry and power is the formula for another Augustan Age. Don’t be afraid of power.

Apples, birches, hayfields and stone walls; simple features like these make up the landscape of four-time Pulitzer Prize winner Robert Frost’s poetry. Known as a poet of New England, Frost (1874-1963) spent much of his life working and wandering the woods and farmland of Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire.

As a young man, he dropped out of Dartmouth and then Harvard, then drifted from job to job: teacher, newspaper editor, cobbler. His poetry career took off during a three-year trip to England with his wife Elinor where Ezra Pound aided the young poet. Frost’s language is plain and straightforward, his lines inspired by the laconic speech of his Yankee neighbors.

But while poems like “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” are accessible enough to make Frost a grammar-school favorite, his poetry is contemplative and sometimes dark—concerned with themes like growing old and facing death. One brilliant example is this poem about a young boy sawing wood, Out, out–

The buzz-saw snarled and rattled in the yard

And made dust and dropped stove-length sticks of wood,

A brief biography of Robert Frost can be found at Poets.org, where there are more samples of his poetry. It includes an account of Frost and JFK.

Frost died on January 29, 1963, in Boston. After his death, an unsigned editorial in the The New York Times, entitled “Ending in Wisdom,” noted:

Robert Frost was more than America’s best-known poet. He was a national figure, almost an institution, a man who went up and down the land saying his poems wherever, it sometimes seemed, two or three Americans were gathered together. He spoke in the language of the common man.

New York Times, January 31, 1963

Robert Frost (Courtesy Library of Congress)

One of my favorite places in Vermont is the Frost grave-site in the cemetery of the First Church in Old Bennington -just down the street from the Bennington Monument, where this video was recorded.

I had a lover’s quarrel with the world

–Robert Frost’s epitaph

I joined veteran newsman Tony Guida on his CUNY TV show “Tony Guida’s New York” to talk about Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly”

Watch here

(Video edited and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2011; revised October 2022)

Add me to the list. I think it is well past time that we ditched Columbus Day. Cities and states around the country are changing the name of the holiday to “Indigenous People’s Day” or “Native American Day” to move this holiday away from a man whose treatment of the natives he encountered included barbaric punishments and forced labor.

In writing about Columbus over more than thirty years, three points stand out when I consider this day that marks his arrival:

•the eradication of the native people he encountered and misnamed los indios through forced labor, executions, and the spread of diseases. (Read “Isabella’s Pigs” chapter in America’s Hidden History)

•the introduction of African slavery by the Spanish after the death of so many Native American people who had been forced into slavery by the Spanish demanded a new labor supply

•the carryover of Europe’s religious wars to the Americas (a subject also discussed in America’s Hidden History)

Aside from those big ripples of history, we have to unlearn a basic idea– that Columbus thought the world was round. He didn’t. And wrote as much.

I found it (the world) was not round . . . but pear shaped, round where it has a nipple, for there it is taller, or as if one had a round ball and, on one side, it should be like a woman’s breast, and this nipple part is the highest and closest to Heaven.

–Christopher Columbus, Log of his third voyage (1498)

To me this a lot more interesting than…

“In fourteen hundred and ninety-two/Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

We all remember that much. But after that basic date, things get a little fuzzy. Here’s what they didn’t tell you–

*Most educated people knew that the world was not flat.

*Columbus never set foot in what would become America.

*Christopher Columbus made four voyages to the so-called New World. And his discoveries opened an astonishing era of exploration and exploitation. But his arrival marked the beginning of the end for tens of millions of Native Americans spread across two continents.

So how did we get a holiday for a man who thought the world was a pear?

In 1892, the 400th anniversary of the arrival of Columbus inspired the composition of the original Pledge of Allegiance and a proclamation by President Benjamin Harrison describing Columbus as “the pioneer of progress and enlightenment.” (Source: Library of Congress, “American Memory: Today in History: October 12”)

That was the patriotic American can-do spirit behind the Columbian Exposition—also known as the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

In 1934, the “progress and enlightenment” celebrated in the Columbus narrative was powerful enough to merit a federal holiday on October 12 – a reflection of the growing political clout of the Knights of Columbus, a Roman Catholic fraternal organization that fought discrimination against recently arrived immigrants, many of them Italian and Irish.

Once a hero. Now a villain. Calendars now add “Indigenous People’s Day” or “Native American Day” to shift this holiday away from a man whose treatment of the natives he encountered included barbaric punishments and forced labor.

“Indigenous Peoples’ Day recognizes that Native people are the first inhabitants of the Americas, including the lands that later became the United States of America. And it urges Americans to rethink history.”

Here are more resources on “Indigenous People’s Day” from the Teaching Tolerance organization

(Video directed and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2015)

When I was a kid in the early 1960s, the autumn social calendar was highlighted by the Halloween party in our church. In these simpler day, the kids all bobbed for apples and paraded through a spooky “haunted house” in homemade costumes –Daniel Boone replete with coonskin caps for the boys; tiaras and fairy princess wands for the girls. It was safe, secure and innocent.

The irony is that our church was a Congregational church — founded by the Puritans of New England. The same people who brought you the Salem Witch Trials.

Here’s a link to a history of those Witch Trials in 1692.

Rooted in pagan traditions more than 2000 years old, Halloween grew out of a Celtic Druid celebration that marked summer’s end. Called Samhain (pronounced sow-in or sow-een), it combined the Celts’ harvest and New Year festivals, held in late October and early November by people in what is now Ireland, Great Britain and elsewhere in Europe. This ancient Druid rite was tied to the seasonal cycles of life and death — as the last crops were harvested, the final apples picked and livestock brought in for winter stables or slaughter. Contrary to what some modern critics believe, Samhain was not the name of a malevolent Celtic deity but meant, “end of summer.”

The Celts also saw Samhain as a fearful time, when the barrier between the worlds of living and dead broke, and spirits walked the earth, causing mischief. Going door to door, children collected wood for a sacred bonfire that provided light against the growing darkness, and villagers gathered to burn crops in honor of their agricultural gods. During this fiery festival, the Celts wore masks, often made of animal heads and skins, hoping to frighten off wandering spirits. As the celebration ended, families carried home embers from the communal fire to re-light their hearth fires.

Getting the picture? Costumes, “trick or treat” and Jack-o-lanterns all got started more than two thousand years ago at an Irish bonfire.

Christianity took a dim view of these “heathen” rites. Attempting to replace the Druid festival of the dead with a church-approved holiday, the seventh-century Pope Boniface IV designated November 1 as All Saints’ Day to honor saints and martyrs. Then in 1000 AD, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to remember the departed and pray for their souls. Together, the three celebrations –All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls Day– were called Hallowmas, and the night before came to be called All-hallows Evening, eventually shortened to “Halloween.”

And when millions of Irish and other Europeans emigrated to America, they carried along their traditions. The age-old practice of carrying home embers in a hollowed-out turnip still burns strong. In an Irish folk tale, a man named Stingy Jack once escaped the devil with one of these turnip lanterns. When the Irish came to America, Jack’s turnip was exchanged for the more easily carved pumpkin and Stingy Jack’s name lives on in “Jack-o-lantern.”

Halloween, in other words, is deeply rooted in myths –ancient stories that explain the seasons and the mysteries of life and death.

The Devil can scripture for his own purpose.

–Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

Throughout history, the Bible has been used to justify many arguments. Often those biblical citations are mistaken, taken out of context, based on a mistranslation –or simply misused. These myths and misconceptions about what is in the Bible led me to write Don’t Know Much About® the Bible.

In American history, the Bible was cited to both justify slavery and call for its abolition. For centuries, slavers pointed to a passage in the book of Genesis to justify the cruel, murderous enslavement of millions of Africans. It is a part of the story of Noah that is not usually told in Sunday school.

After building the ark, loading the animals two by two, and weathering the Flood, Noah and his family reach dry land. Noah begins to plant and grows some grapes to make wine:

20 And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard:

21 And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent.

22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without.

23 And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness.

24 And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him.

25 And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.

26 And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

27 God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

–Genesis 9:20-27 King James Version

The passage is a bit garbled. But the “curse of Ham” was used to justify the enslavement of people of African ancestry, who were believed to be descendants of Ham, through his son Canaan. This theory was widely held during the eighteenth to twentieth centuries to justify both slavery and the racist notion of the inferiority of Blacks, and added to the many biblical references used by Christians to justify enslavement.

Gradually, other Christians argued that to enslave another human was a basic contradiction of Jesus’s teachings, including the Christian version of the “Golden Rule”:

Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets.

–Matthew 7: 12 (King James Version)

There are many other instances of the Bible and religion being used as a weapon throughout American history, including the anti-Catholic “Bible Riots” in Philadelphia in 1844, which I wrote about in A Nation Rising.

Read more about the traditions of religious intolerance in my Smithsonian article “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= (This video was originally posted May 2012. It was produced and directed by Colin Davis.)

Memorial Day brings thoughts of duty, honor, courage, sacrifice and loss. The holiday, the most somber date on the American national calendar, was born in the ashes of the Civil War as “Decoration Day,” when General John S. Logan –a-veteran of the Mexican and Civil Wars, a prominent Illinois politician and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union fraternal organization –called for May 30, 1868 as the day on which the graves of fallen Union soldiers would be decorated with fresh flowers in his “General Orders No. 11.”

“We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the Nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds.”

Pointedly, Logan’s order was seen as a day to honor those who died in the cause of ending slavery and opposing the “rebellion.”

Every year at this time, I spend a lot of time talking about the roots and traditions of Memorial Day.

It’s not about the barbecue or the Mattress Sales. Obscured by the holiday atmosphere around Memorial Day is the fact that it is the most solemn day on the national calendar. This video tells a bit about the history behind the holiday.

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

One of the most famous symbols of the loss on Memorial Day is the Poppy, inspired by this World War I poem by John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields”

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky,

The larks, still bravely singing, fly,

Scarce heard amid the guns below.We are the dead; short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.Take up our quarrel with the foe!

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high!

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.Source: The poem is in the public domain courtesy of Poets.org

Have a memorable Memorial Day!

The U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs offers more resources on the history and traditions of Memorial Day.

(Images in video: Courtesy of the Library of Congress and Flanders Cemetery image Courtesy of the American Battle Monuments Commission)

As the nation reckons with its horrific history of slavery, what do we do about George Washington?

You can also read my post “What Do We Do About George?”

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919 was the most deadly outbreak of disease in modern times. It was completely connected to the last year of World War I. And it has some important lessons today as the world confronts another deadly pandemic. This short video looks at the history of one pandemic while we live through another.

February 12 used to mean something special — Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday. It was never a national holiday but it was pretty important when I was a kid and we got the day off from school in my hometown.

The Uniform Holidays Act in 1971 changed that by creating Washington’s Birthday as a federal holiday on the third Monday in February. It is NOT officially “Presidents Day.”

But it is still a good excuse to talk about Abraham Lincoln, especially since his real birthday is on the calendar.

“Honest Abe.” “The Railsplitter.” “The Great Emancipator.” You know some of the basics and the legends. But check out this video to learn some of things you may not know, but should, about the 16th President.

Here’s a link to the Lincoln Birthplace National Park

This link is to the Emancipation Proclamation page at the National Archives.