(Post updated May 20, 2024)

Some governors would have us teach “the basics.” So here goes:

LET’S SET THE RECORD STRAIGHT— Memorial Day is about Slavery

It is not about swimsuit sales, the start of summer, or the hot dogs on the barbie.

Memorial Day, the most solemn occasion on the national calendar now honors the nation’s war dead. But it was born out of the the Civil War, which was fought because of slavery, America’s original sin. Memorial Day is about a nation “conceived in liberty” but born in shackles.

In these fraught times, when teaching history has become so contentious, we must tell it straight when we observe the history behind the holiday. Here are some basic facts:

1) Memorial Day was conceived as Decoration Day, first marked in May 30, 1868 by a proclamation of General John Logan, leader of a powerful Civil War veterans group. His original proclamation –“General Orders, No. 11”– read, in part: “Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains and their deaths the tattoo of rebellious tyranny in arms.”

The day was an occasion for visiting the cemetery and decorating the graves of fallen Union soldiers who died in the Civil War.

2) The Civil War was fought over slavery. The “states rights” argument was put forward by “Lost Cause” apologists and eventually accepted by educators who wanted to diminish the significant role of slavery both in American history and in bringing about the war.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

Read more about the divisive history of Memorial Day in an earlier post.

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

The truth matters. Now more than ever. So, once and for all, we must set the record straight.

As we observe Memorial Day, a day for honoring our nation’s war dead, let us emphasis these truths about America’s deep history of slavery.

Here are five important points that illustrate the through-line of slavery in American history, from the founding through the Civil War:

READ MORE in my article “Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles” (Social Education, March-April 2020)

(Previous post updated 8 May, 2024)

Happy 140th Birthday!

Harry Truman, 33rd President of the United States, was born on May 8, 1884.

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

It was on his birthday in 1945 that Truman was able to tell Americans that the war in Europe was over with the surrender of Germany.

THIS IS a solemn but a glorious hour. I only wish that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly over all Europe. For this victory, we join in offering our thanks to the Providence which has guided and sustained us through the dark days of adversity.

Described as “a minor national figure with a pedestrian background,” Truman was a World War I veteran and a Senator from Missouri when Franklin D. Roosevelt chose him to become his running mate in the 1944 election. Truman became vice president when FDR won his fourth term and then took office on April 12, 1945 when FDR died.

When he took office, Truman had been largely left “out of the loop” by Roosevelt as World War II entered its final months. Truman did not know of the existence of the “Manhattan Project” and the development of the atomic bomb until he became president. Then he had to make the decision to use it against the Japanese.

Fast Facts

•Truman was a member of the Sons of the Revolution and the Sons of Confederate Veterans

•He wanted to attend West Point but poor eyesight kept him out. He enlisted in the Missouri National Guard and served as the commander of an artillery battery in World War I.

•Before entering politics, he was a farmer, bank clerk, insurance salesman and owner of a failed haberdashery store.

•As president he once threatened to punch the nose of a newspaper critic who had given his daughter a poor review after her debut singing recital. Margaret Truman went on to greater fame as a mystery novelist, beginning with Murder in the White House published in 1980.

Harry S. Truman died on December 26, 1972.

The Truman Library and Museum is located in Independence, Missouri

Read more about Truman, his life and administration in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents. Truman is also featured in the Berlin Battle chapter of The Hidden History of America at War.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on March 25, 1911 from front page of The New York World (Source: [Post revised from original on 3/25/2011]Cornell University ILR School Kheel Center © 2011)

Can anything positive or hopeful emerge from a terrible tragedy? That is a question we are all pondering as we still contend with a pandemic that swept across the United States and the world.

We are also asking about the human costs of “business as usual.”

So it is a moment to consider of one of the greatest tragedies of modern American history.

On March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York caught fire and 146 people died, most of them women between the ages of 14 and 23, many were Jewish and Italian immigrants. They had been trapped inside the building, its doors chained shut.

Cornell University’s Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation offers a web exhibit on the Triangle Factory Fire.

These are the names of the 146 people who died that day.

A new memorial commemorates the event, the memory of the lost, and the meaning of the tragedy.

It was a disaster that shook the American conscience and sparked the nation’s Labor movement.

“Look for the union label.”

If you are of a certain generation, you may recognize those words instantly. They are the first line of a song that became a 1970s advertising icon.

Sung by a swelling chorus of lovely ladies (and a few men) of all colors, shapes and sizes, it was the anthem of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union.

Airing as American unions began to confront the long, steady drain of jobs to cheaper foreign labor markets, the song implored us to look for the union label when shopping for clothes (“When you are buying a coat, dress or blouse”).

Seeing these earnest women, thinking of them at their sewing machines, made us race to the closet and check our clothes for that ILGWU tag. (“It says we’re able to make it in the USA.”)

The International Ladies Garment Worker Union was born in 1900, in the midst of the often-violent period of early 20th century labor organizing when brutal working conditions and child labor were the norm in America’s mines and factories.

One of the companies the union attempted to organize was the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory at what is now Greene Street and Washington Place in New York’s Greenwich Village.

A walkout against the firm in 1909 helped strengthen the union’s rolls and led to a union victory in 1910. But the Triangle Shirtwaist Company –which would chain its doors shut to control its workers— earned infamy when a fire broke out on March 25, 1911 and 146 workers were trapped in the flaming building and died. Some jumped to their deaths.

A police officer and others with the broken bodies of Triangle fire victims at their feet, look up in shock at workers poised to jump from the upper floors of the burning Asch Building. (Credit: Cornell University ILR School Kheel Center ©2011)

The two owners of the factory were indicted but found not guilty. The tragedy helped galvanize the trade union movement and especially the ILGWU.

On this anniversary of that dreadful event, it is worth remembering that American prosperity was built on the sweat, tears and blood of working men and women. Immigration and jobs are the issue again today, just as they were more than a century ago.

The Library of Congress also offers numerous resources on the tragedy.

On February 28, 2011, American Experience on PBS aired a documentary film about the tragedy and the period.

The site is part of New York University and a National Historic Landmark.

March 16 marks the anniversary of the birth in 1751 of America’s fourth President, James Madison, also known as “The Father of the Constitution.”

Like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, his Virginia predecessors in the presidency, Madison embodied the “Great Contradiction”– that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

READ MY ARTICLE “THE AMERICAN CONTRADICTION,” on teaching the history of American slavery in Social Education.

Small in stature and overshadowed by the more famous Washington and Jefferson, Madison is counted among of the greatest of the Founding Fathers for the breadth and influence of his contributions. Like many of the Founders, Madison had reservations about slavery as a contradiction to this ideals, but did little to end the institution. He hoped that slavery would end after the foreign trade was abolished and thought that enslaved African-Americans should be emancipated and returned to Africa.

The story of Paul Jennings, who was enslaved by Madison and wrote a memoir of working as a servant in the White House, is told in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751 in Port Conway, Virginia. The son of a tobacco planter and somewhat sickly as a child, he went north to study at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton). There he came under the influence of the college President, John Witherspoon, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence, and made a friend of fellow student, Aaron Burr, son of the College’s founder.

Returning to Virginia, Madison became involved in patriot politics and became a close colleague of his neighbor Thomas Jefferson, serving as Jefferson’s adviser and confidant during the war years while Jefferson was Governor of Virginia.

In 1794, he married the widow Dolley Payne Todd, having been formally introduced by his college friend Aaron Burr.

A few Madison Highlights:

•Secured passage of the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786), an act that is a cornerstone of religious freedom in America. As part of that effort, he wrote the influential Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments. (I discuss the “Remonstrance” in my article “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance” in the October 2010 Smithsonian.)

•Was the moving force behind the Constitutional Convention and was one of the principal authors of the Constitution. Madison’s support of the electoral system is laid out in this essay by Yale professor Akhil Reed Amar “The Troubling Reason the Electoral College Exists.”

•With Alexander Hamilton and John Jay was one of the authors of The Federalist Papers (Resources from the Library of Congress), arguments in favor of the ratification of the Constitution

•Was principal author of the Bill of Rights, which he originally thought unnecessary

Following ratification of the Constitution, Madison was a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia and a powerful Congressional ally of George Washington.

•Drafted the first version of Washington’s Farewell Address

•Supervised the Louisiana Purchase as Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of State

•Presided over the ill-prepared nation during the War of 1812, the “second war of independence”

I believe there are more instances of the abridgment of the freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachments of those in power than by violent and sudden usurpations. –June 16, 1788

Madison died on June 28, 1836 at Montpelier, at age 85. Enslaved servant Paul Jennings was at his bedside and later recalled in a memoir that Madison died, “as quietly as the snuff of a candle goes out.”

James Madison is buried at Montpelier.

LINKS:

The Library of Congress Resource Collection on James Madison.

Madison’s Major Papers and Inaugural Addresses can be found at the Avalon Project of the Yale Law School.

Imacon Color Scanner

(March 15, 2024: Revision of original post of March 15, 2014. Video created and directed by Colin Davis.)

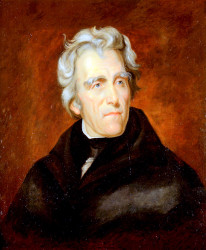

Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States, was born on March 15, 1767.

His birthplace was a cabin on the border of both South and North Carolina (the precise location is uncertain).

When this was last posted, he had fallen from favor and was going to be moved to the back side of the $20 in favor of Harriet Tubman. That decision was shelved by the previous administration and in 2021 was put back on track under the Biden administration.

In his day and ever since, Andrew Jackson provoked high emotions and sharp opinions. Thomas Jefferson once called him, “A dangerous man.”

His predecessor as president, John Quincy Adams, a bitter political rival, said Jackson was,

“A barbarian who could not even write a sentence of grammar and could hardly spell his own name.”

His place and reputation as an Indian fighter began with a somewhat overlooked fight against the Creek nation led by a half-Creek, half-Scot warrior named William Weatherford, or Red Eagle following an attack on an outpost known as Fort Mims north of Mobile, Alabama.

The video above (created in 2014) offers a quick overview of Weatherford’s war with Jackson that ultimately led the demise of the Creek nation.Like Pearl Harbor or 9/11, it was an event that shocked the nation. Soon, Red Eagle and his Creek warriors were at war with Andrew Jackson, the Nashville lawyer turned politician, who had no love for the British or Native Americans.

On March 27, 1814, Jackson’s troops defeated Red Eagle and his Creek warriors, killing more than 800 Natives–women, children, and the elderly as well as warriors. Jackson’s soldiers cut off the noses of the dead to tally their numbers. Other soldiers cut off strips of skin to make reins for their horses. (A Nation Rising, page 66-68)

On August 9, 1814, Major General Andrew Jackson signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson ending the Creek War. The agreement provided for the surrender of twenty-three million acres of Creek land to the United States. This vast territory encompassed more than half of present-day Alabama and part of southern Georgia.

Resources from Library of Congress.

The complete story of the Red Creek War is told in my book A Nation Rising.

Andrew Jackson died on June 8, 1845. He was surrounded by many of the household servants he had enslaved. He told them:

Tombstone of Alfred Jackson, enslaved servant of Andrew Jackson. (Author photo © 2010)

“I want all to prepare to meet me in heaven….Christ has no respect to color.”

The story of one of those people, Alfred Jackson, is told in my recent book, In the Shadow of Liberty. Alfred Jackson is buried in the garden at the Hermitage, near Andrew Jackson’s gravesite.

You can also read more about William Weatherford, Andrew Jackson, and Jackson’s role in American history in A NATION RISING. Andrew Jackson’s life and presidency are also covered in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents.

Portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart (Source: Clark Institute Williamstown, Mass.)

[Originally posted July 2, 2020; revised February 22, 2024]

Today is actually George Washington’s Birthday. Maybe you thought you celebrated last Monday (not President’s Day). Seeing as the holiday falls in February –Black History Month– it is a good time to bring these two crucial pieces of history together.

There is no question that Washington’s accomplishments were central to the foundation of the Republic. His command during the Revolution. His role at the Constitutional Convention, where he presided. His two terms as president, in which he established many presidential precedents and then stepped aside. For these achievements, I described him as one of America’s greatest presidents. He was, as one biographer described him, the “Indispensable Man.”

But like many of the Founders, the “Father of Our Country” enslaved people. Inheriting ten people from his father at age eleven, Washington held more than three hundred men, women, and children in bondage at the time of his death in 1799. While one man was freed in Washington’s will, the others had to wait for Martha Washington to die. And roughly half of those people remained enslaved, parceled out among the Custis family, as part of the estate of Martha’s first husband.

In other words, George Washington was an enslaver from childhood to grave. And we have the receipts.

He once raffled off whole families in lots, including small children separated from parents. He later purchased four children at an estate sale, sending two dark-skinned boys to do fieldwork while two “mulatto” boys became house servants. Frank Lee became Mount Vernon’s butler and his brother Billy Lee served as Washington’s valet, his “loyal manservant,” for some thirty years.

The last remaining set of Washington’s dentures (Courtesy: Mount Vernon Ladies Association)

Washington’s own journal records that he purchased teeth pulled from the mouths of enslaved people, presumably to be fitted into his dentures. In exchange for a grocery list of rum, molasses, fruits, and sweetmeats, he once shipped off a man named Tom, a repeat runaway, and at least two other men to the cane fields of the West Indies.

And then there is the heroic Washington’s actions at Yorktown. After his signal victory over the British in 1781, General Washington wasted no time in recovering Esther, Lucy, Sambo Andersen, and fourteen others who had escaped Mount Vernon when offered the chance. They were among thousands of enslaved people who had fled to the British in hopes of emancipation. While Washington won America’s liberty, they lost theirs.

Did this inconsistency trouble Washington? The contradiction between his devotion to freedom while enslaving people did seem to prick his conscience. In 1786, he confided to fellow Founder Robert Morris, “there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it [slavery].”

But he did precious little to make it happen, either while presiding over the convention that cemented slavery in the Constitution, or as first president. After Philadelphia became the nation’s capital in 1790, President Washington shuttled enslaved servants in and out of the city to evade a Pennsylvania law that called for the emancipation of enslaved males residing in the state for more than six months. In 1793, he signed the Fugitive Slave Act, making assistance to runaways a federal offense.

When Ona Judge, Martha Washington’s enslaved maid, learned she would be given away as a wedding gift, she escaped from the home of the president in 1796. He advertised a ten-dollar reward for her return and spent the next three years trying to track down and recover a woman who had risked all for freedom.

For more than two centuries, these contradictions were given little weight by Washington’s admirers. The little boy who couldn’t tell a lie was immortalized as “First in the hearts of his countrymen.” The enslavement of human beings, especially by one of America’s most admired presidents, remained the dirty secret long concealed by textbooks and popular culture.

But a stunning moment of correction has arrived. It begs the questions:

Will George Washington’s picture be removed from the currency?

Will protestors project the images of African-American heroes onto Washington’s stern visage carved on Mt. Rushmore, as Harriet Tubman’s face now adorns Robert E. Lee’s statue in Richmond?

Washington Monument (Courtesy National Parks Service https://www.nps.gov/wamo/learn/historyculture/index.htm)

What about the Washington Monument?

We are now in a teachable moment. What we do is limited only by our creativity and the courage to be honest. We won’t take a chisel to the Washington Monument or spray paint it with graffiti. But we should teach students and all Americans that Washington was a flawed man who committed a crime against humanity while also building the nation. This was the “gross injustice and cruelty” that Frederick Douglass famously called out in his 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Remaining silent on that injustice and cruelty is no longer an option. Because this is one of those “self-evident” truths. The United States was “conceived in liberty,” but born in shackles. We can no longer honor Washington’s indispensable achievements without recognizing his original sin.

What better occasion than Washington’s Birthday to do that.

“I must go into the Presidential chair the inflexible and uncompromising opponent of every attempt on the part of Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia against the wishes of the slaveholding states, and also with a determination equally decided to resist the slightest interference with it in the states where it exists.”

–Inaugural Address, March 4, 1837

(Post of 12/5/2016; reposted 12/5/2023)

Martin Van Buren Eighth U.S. President Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

OK –Literally.

Martin Van Buren, the eighth President of the United States, was born on December 5, 1782 in Kinderhook, New York, making him the first American president born a U.S. citizen. Van Buren was also known as “Old Kinderhook, or “OK,” the origin of that American expression.

Van Buren was also the first New Yorker elected President. He was a crafty political power broker who mastered the art of “machine politics” and helped bring New York into Andrew Jackson’s column in 1828. He became Jackson’s Secretary of State and later his vice president. He won the presidential election of 1836. But his presidency was tainted by the Panic of 1837, a deep economic depression that lasted seven years. He was defeated in 1840 by William Henry Harrison of the Whig Party.

Fast Facts:

•Van Buren was the first president not of English descent. Growing up in a Dutch-speaking household, he was also the only president who spoke English as a second language.

•As a young attorney, he became the protege of Aaron Burr. Due to a passing resemblance and their political and professional connections, it was rumored that he was Burr’s son, gossip thoroughly dismissed by historians.

•Elected Governor of New York in November 1828, Van Buren took the office on January 1, 1829 but resigned on March 12, 1829 to become secretary of state, making him the shortest tenured governor in New York history.

•During Van Buren’s administration, the removal of native Americans from the Southeast accelerated including the removal of the Cherokee on the “Trail of Tears.”

•The Congressional “gag rule” was passed during his presidency; the rule forbid any discussion of petitions relating to slavery, including banning slavery in Washington, D.C, as mentioned in Van Buren’s inaugural address above.

•Failing to win the Democratic nomination in 1844, Van Buren became the first president to run on a third party ticket when he joined the Free Soil Party as its candidate in 1848.

You can read more about his life at the Martin Van Buren Historical Site (National Parks Service) and at the Library of Congress.

And read more about Van Buren and his administration in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

“Why do Americans and Canadians Celebrate Labor Day?”

This Ted-Ed animated video explains the history of the holiday is a few years old. But it still matters today. (Reposted from 9/1/2014)

You can also view it on YouTube:

You can read more about the history and meaning of Labor Day in this piece I wrote for CNN a few years ago:

“The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”

Read more about the period of labor unrest in Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

(Originally posted on 1/24/2013; revised 8/11/2024)

Photo courtesy The Mount https://www.edithwharton.org/discover/edith-wharton/

You may have been assigned to read Ethan Frome in high school. Or you have read or seen the grand dramas of New York Society, The House of Mirth or The Age of Innocence. That’s how you know the name Edith Wharton.

Born in New York City, January 24, 1862: Edith Newbold Jones, who achieved fame as Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1921 (for The Age of Innocence).

But the other lesser-known aspect of Wharton’s life is her experience in France during World War I, where she founded hospitals and refugee centers for women and children.

Romance, scandal and ruin among New York socialites—long before this was the stuff of People, and “Gossip Girl,” it was the subject matter for Edith Wharton’s most famous works. In such novels as The House of Mirth (1905) and The Age of Innocence (1920), Wharton painted detailed, acid portraits of high society life. In doing so, she created heartbreaking conflicts beneath the façade of wealth and manners. Again and again, characters like Newland Archer and Lily Bart were forced to choose between conforming to social expectations and pursuing true love and happiness. Her most famous work set outside the realm of high-tone New York was Ethan Frome (1911), set in wintry, rural Massachusetts.

Edith Wharton in France during World War I (Photo: Courtesy The Mount Edith Wharton’s Home)

Wharton had spent years in Europe as a child and teenager. But she moved to France in 1910 while war in Europe was on the horizon and her marriage to socialite Teddy Wharton disintegrated.

Once the war broke out, she also wrote urging the United States to join the war. Then she saw the hardship caused as the fighting that tore across Europe starting in August 1914 created masses of refugees.

American novelist Edith Wharton set up workshops for women all over Paris, making clothes for hospitals as well as lingerie for a fashionable clientele. She raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for refugees and tuberculosis sufferers and ran a rescue committee for the children of Flanders, whose towns were bombarded by the Germans. Her friend and fellow author Henry James called her the “great generalissima”.

Source: Radio France International: “Edith Wharton-The American novelist who joined France’s WWI effort”

She started in her neighborhood with sewing workshops that eventually employed more than 800 women, opened hostels for tuberculosis patients and refugee children, hosted benefit concerts, sent dispatches from the war front.

In the first year of her work, her Children of Flanders Rescue Committee could record:

Refugees assisted: 9,229

Meals served: 235,000

Refugees for whom employment has been found: 3,400

Garments distributed: 48,333

For her wartime work, in 1916 Wharton was awarded France’s highest decoration – a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Edith Wharton died in Paris in 1937 and is buried in Versailles. Here is her New York Times obituary.

Edith Wharton is one of 58 writers featured in Great Short Books

The Mount is Wharton’s restored home in the Berkshires in Massachusetts.

[Originally posted August 10, 2015; updated 8/10/2023]

“We are challenged with a peace-time choice between the American system of rugged individualism and a European philosophy of diametrically opposed doctrines— doctrines of paternalism and state socialism. . . . Our American experiment in human welfare has yielded a degree of well- being unparalleled in all the world. It has come nearer to the abolition of poverty, to the abolition of fear of want than humanity has ever reached before.” –Herbert Hoover, “Campaign Speech” (October 22, 1928)

Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover in their Washington, DC home the morning after he was nominated to run for president (1928). (Courtesy: The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum)

Born on August 10, 1874, Herbert Clark Hoover, the 31st president of the United States. Herbert Hoover was born into a Quaker family in Iowa, and orphaned at nine. He went to live with relatives in Oregon. A college education at Stanford led to a career in the mining industry and a great personal fortune. You may know that he was the Republican president when the Stock Market crashed in 1929 and he attempted to lead the country through the first years of the Great Depression. Hoover was defeated by Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932.

But you may not know that Hoover was considered a hero and savior to millions of people. First during World War I, he had organized food relief programs in war-torn Belgium.

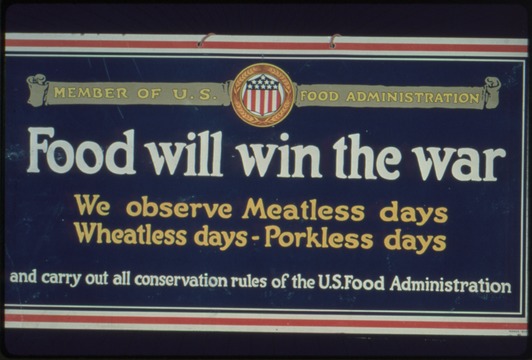

According to the Herbert Hoover Presidental Museum and Library, Hoover was named to head the U.S. Food Administration, which guided the effort to conserve resources and supplies and to feed America’s European allies.

National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/512516

“Hoover became a household name—‘to Hooverize’ meant to economize on food. Americans began observing ‘Meatless Mondays’ and ‘Wheatless Wednesdays’ and planting War Gardens.”

Later, in the aftermath of World War I, Russia was in the throes of Europe’s greatest calamity since the days of the Black Plague. More than five million died in the new Soviet Russia when famine struck. In 1921, Herbert Hoover led America’s response to the “Great Famine,” subject of a PBS documentary and is credited with saving millions of lives.

Hoover gets hard knocks for the hard times of the Depression and his flawed response to the problems confronting America. But others assess him more generously. Historian Richard Norton Smith once noted:

“Herbert Hoover saved more lives through his various relief efforts than all the dictators of the 20th century together could snuff out. Seventy years before politicians discovered children, he founded the American Child Health Association. The problem is, Hoover defies easy labeling. How can you categorize a ‘rugged individualist’ who once said, ‘The trouble with capitalism is capitalists; they’re too damn greedy.’ ”

“Remembering Herbert Hoover,” New York Times, August 10, 1992

During the food scarcity in the height of the Covid pandemic, I wrote about Hoover’s wartime efforts in this post: “Where Is Herbert Hoover When We Need Him?”

Some Fast Facts about Herbert Hoover:

✱ Hoover was the first president born west of the Mississippi.

✱ His wife, Lou, was the only female geology major at Stanford when they met. They later collaborated on a translation from Latin of a mining and metallurgy text, De Re Metallica, published in 1912. While they lived in China, the Hoovers lived through the 1900 Boxer Rebellion and both learned Chinese, and they sometimes spoke to each other in Chinese at the White House.

✱ Hoover’s inaugural in 1929 was the first to be recorded on talking newsreel.

✱ Hoover was the first of two Quaker presidents. (The other was Richard M. Nixon.)

President Hoover died on October 20, 1964 in New York City. He was 90 years old. Hoover’s New York Times obituary. The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum offers archival materials and online exhibitions.

You can read more about Hoover in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Books/Random House Audio)