[Originally posted in 2020 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II and the transformation of the modern world; Revised July 30, 2024]

From the “Trinity” Test to Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Japan’s Surrender:

The Month That Changed the World

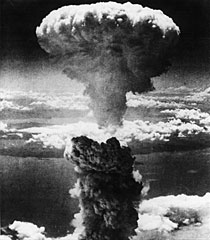

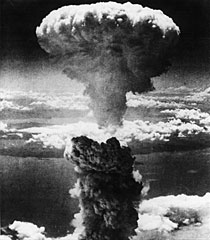

The atomic bomb cloud over Hiroshima Source: National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542192

The July 21, 2023 release of Oppenheimer, the critically acclaimed film by director Christopher Nolan about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the man who led the development of the atomic bomb, has brought renewed attention in this chapter of American and world History. The successful test of the bomb in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945 set in motion a series of world-changing events in the final weeks of World War II.

The following timeline summarizes the momentous landmarks that helped make the modern world between July 16 and August 15, 1945.

On August 6, 1945, the New York Times asked:

“What is this terrible new weapon?”

(New York Times, August 6, 1945: “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan”)

The story followed the announcement made that day by President Harry S. Truman:

“SIXTEEN HOURS AGO an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British ‘Grand Slam’ which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.”

August 6, 1945

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

(“Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima”: Truman Library and Museum)

The use of the first atomic bomb followed the successful test detonation –the goal of the wartime Manhattan Project — and the beginning of a series of events that reshaped the world in the final weeks of World War II.

•July 16, 1945 the first atomic device, nicknamed “the Gadget,” is detonated in the “Trinity” test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. Read this account of the test in National Geographic.

New York Times reporter Dennis Overbye visited the site in 2021. His report “Touring Trinity, the Birthplace of Nuclear Dread”:

“The detonation created a crater eight feet deep, a half-mile wide and lined with glassy pebbles called trinitite: sand that had been swept up in the fireball, vaporized and then fell back down in molten radioactive droplets.

By many accounts, J. Robert Oppenheimer uttered a passage he recalled from the Hindu epic Bhagavad Gita:

“Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.”

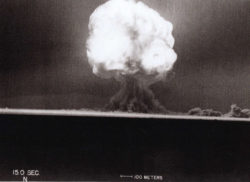

The Trinity test, 15 seconds after detonation. Photo courtesy of David Wargowski Source: National Museum of Nuclear Science & History

Read more about the test in “The First Light of Trinity” by Alex Wellerstein in The New Yorker.

One of Robert Oppenheimer’s biographers, Kai Bird, has also written “Oppenheimer, Nullified and Vindicated,” also in The New Yorker.

UPDATE July 18, 2023“The Real History Behind Christopher Nolan’s ‘Oppenheimer'” (Smithsonian)

“Oppenheimer provides an opportunity to revisit this charismatic, contradictory man and reconsider how previous attempts to tell his story have succeeded—and failed—at fathoming one of the 20th century’s most fascinating public figures.”

UPDATE: July 20, 2023:

“Trinity Nuclear Test’s Fallout Reached 46 States, Canada, and Mexico, Study Finds”

“A new study, released on Thursday ahead of submission to a scientific journal for peer review, shows that the cloud and its fallout went farther than anyone in the Manhattan Project had imagined in 1945. Using state-of-the-art modeling software and recently uncovered historical weather data, the study’s authors say that radioactive fallout from the Trinity test reached 46 states, Canada and Mexico within 10 days of detonation.”

“Trinity Nuclear Test’s Fallout Reached 46 States, Canada, and Mexico, Study Finds,” New York Times (July 20, 2023)

Over the next weeks, the world would be transformed, with the arrival of the Atomic Age, Japan’s surrender, the end of World War II, the charter of the United Nations, and the beginning of the Cold War.

The development, testing, and use of atomic bombs is documented by the National Museum of Nuclear Science and History.

L to R: British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, President Harry S. Truman, and Soviet leader Josef Stalin in the garden of Cecilienhof Palace before meeting for the Potsdam Conference in Potsdam, Germany. National Archives Identifier 198958

•July 17 In Potsdam, near Berlin in defeated Germany, President Harry S. Truman comes face to face with the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. Truman had taken office upon the death of President Roosevelt on April 12, 1945 without knowledge of the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb’s existence. Having been told about the potential weapon, Truman is informed of the successful “Trinity” test while meeting Soviet Strongman Stalin with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the European postwar conference.

“I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument.”

In his diary, Truman adds: “He said he had and that he had some more questions to present. I told him to fire away. He did and it is dynamite—but I have some dynamite too which I’m not exploding now. . . . I can deal with Stalin. He is honest—but smart as hell.” (National Archives)

Read about Stalin’s rise to power in

Strongman

Following the New Mexico test success, the components of the atomic bomb are loaded onto the USS Indianapolis in San Francisco for transport to an airbase on Tinian Island in the Pacific. Many of the crew of nearly 1,200 men have no idea what the ship is carrying.

•July 19 In the United States, Congress approves the Bretton Woods agreement, an international pact designed to avoid postwar financial crises like those that followed World War I. The agreement creates the International Money Fund and what later becomes the World Bank.

The Japanese cities of Choshi, Hitachi, Fukui and Okazaki are struck by 600 B-29 Superfortress bombers dropping some 4,000 tons of bombs — the largest employment of the bomber to date.

The USS Indianapolis reaches Pearl Harbor in the first leg of its voyage to deliver the atomic bomb components.

https://catalog.archives.gov/id/515009

• July 21 “A senior US Army Air Force intelligence officer in the Pacific distributed a report declaring: ‘The entire population of Japan is a proper Military Target . . . THERE ARE NO CIVILIANS IN JAPAN.’” Richard B. Frank via World War II Museum.

Truman and Churchill at Potsdam

https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/63-1455-39

In Potsdam, Truman and Churchill privately agree to use the atomic bomb if Japan does not surrender. Read about Truman’s decision from the National Park Service Harry S. Truman National Historic Site.

•July 22 In what is described as the last surface battle of World War II, the U.S. Navy sinks Japanese supply ships in the “Battle of Sagami Bay” (“Tokyo Bay”). Naval bombardments of the Japanese mainland continue, along with B-29 bombing raids striking Japanese cities.

In China, the American Far East Air Force attacks Japanese troops, airfields, and shipping near Shanghai.

•July 23 In Potsdam, Secretary of War Henry Stimson receives atomic bomb target list. In order of choice they are: Hiroshima, Kokura, and Niigata. He also receives an estimate of atomic bomb availability: “Little Boy” should be ready for use on Aug. 6, second “Fat Man-type” by Aug. 24. There are plans for a total of seven bombs available by December.

•July 24 Truman informs Stalin of a “new weapon of unusual destructive force.”

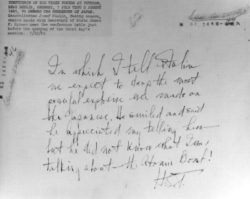

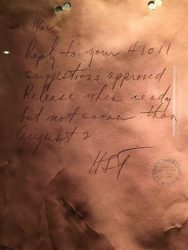

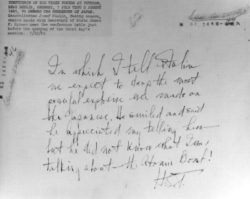

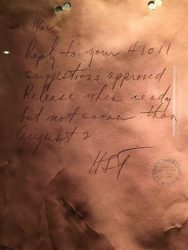

“In which I tell Stalin we expect to drop the most powerful explosive ever made on the Japanese. He smiled and said he appreciated my telling him–but he did not know what I was talking about–the Atomic Bomb! HST”

–Truman Library and Museum

Truman’s note on back of photograph from Potsdam Conference describing his conversation with Stalin about the atomic bomb. Source: Truman Museum https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/63-1456-46a

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

But Stalin already knows about the atomic bomb because of a network of spies inside the Manhattan Project. The Soviet push to capture Berlin in April and May 1945 was motivated in part by Stalin wanting to capture German scientists working on a Nazi atomic bomb and tons of uranium held in a Berlin lab. This episode is recounted in the “Berlin Stories” chapter of my book The Hidden History of America at War.

• July 25 Truman writes in his diary that he has made the decision to use “the most destructive bomb in the history of the world… I have told the Sec. of War, Mr. Stimson, to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children.”

Sources: Truman Library and Museum National Security Archive, George Washington University

• July 26 British general election returns are announced; Prime Minister Winston Churchill is defeated and replaced by Clement Attlee.

“The landslide victory comes as a major shock to the Conservatives following Mr Churchill’s hugely successful term as Britain’s war-time coalition leader, during which he mobilised and inspired courage in an entire nation.” —BBC

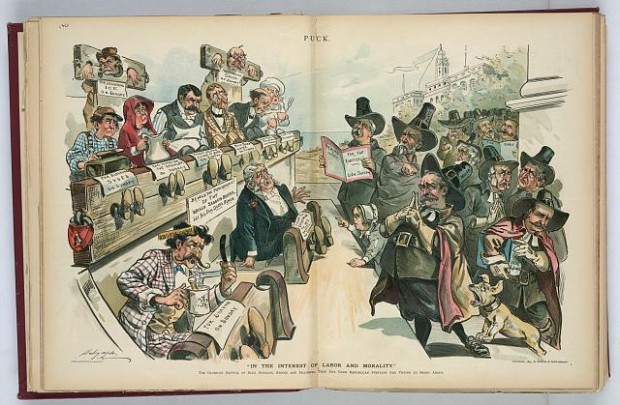

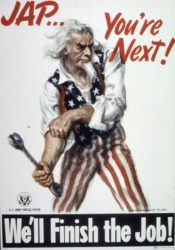

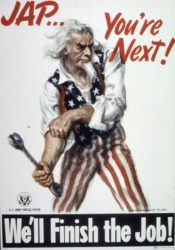

U.S. Propaganda poster (Source National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/513563)

At the Potsdam Conference, the Potsdam Declaration demands an “Unconditional surrender” by Japan. Issued by Great Britain, China, and the U.S., it threatens:

“The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.”

The USS Indianapolis reaches Tinian that day.

USS Indianapolis 10 July 1945, after final overhaul and repair of combat damage. Photograph from the Bureau of Ships Collection in the U.S. National Archives (Naval History and Heritage Command https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/2017/08/24/lest-we-forget-uss-indianapolis-and-her-sailors/)

“Indianapolis departed San Francisco on 16 July 1945, foregoing her post-repair shakedown period. Touching at Pearl Harbor on 19 July, she raced on unescorted and reached Tinian on 26 July, covering some 5,000 miles from San Francisco in only ten days.”

After delivering the atomic bomb components, the ship departs for Guam and the Philippines.

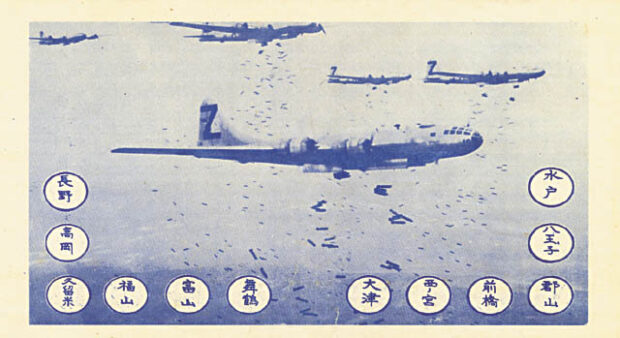

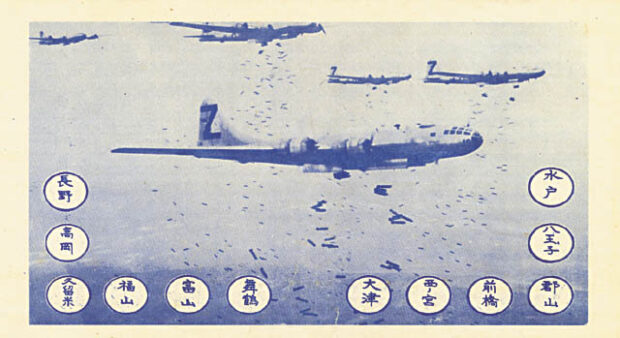

• July 27 American B-29 SuperFortress bombers drop 600,000 leaflets over eleven Japanese cities warning that they are targets of bombings.

“But, unfortunately, bombs have no eyes. So, in accordance with America’s humanitarian policies, the American Air Force, which does not wish to injure innocent people, now gives you warning to evacuate the cities named and save your lives.” –from a “LeMay Leaflet,” named for General Curtis LeMay, architect of the Pacific bombing campaign. Image Courtesy Alex Wellerstein via Atomic Heritage Foundation)

In England, Winston Churchill has a final meeting with his joint chiefs of staff.

•July 28 In New York City, an Army B-25 bomber on a routine mission flies into the Empire State Building –then the world’s tallest skyscraper. Three crew members and eleven people in the building are killed.

“B-25 Mitchell bomber smashed beyond recognition into Empire State Building. This is a picture of the wreckage-strewn 79th floor where the bomber tore a 18-foot hole in wall. Propeller is embedded in the wall at the left.” Source: New York Daily News

“I was at the file cabinet and all of a sudden the building felt like it was just going to topple over,” [office worker Gloria] Pall said. “It threw me across the room, and I landed against the wall. People were screaming and looking at each other. We didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know if it was a bomb or what happened. It was terrifying.” Source: National Public Radio

In Potsdam, newly-elected Prime Minister Clement Attlee of the Labour Party arrives to rejoin the talks which are nearly concluded. Attlee led post-war UK until 1951.

“As Prime Minister, he enlarged and improved social services and the public sector in post-war Britain, creating the National Health Service and nationalising major industries and public utilities. Attlee’s government also presided over the decolonisation of India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon and Jordan, and saw the creation of the state of Israel upon Britain’s withdrawal from Palestine.” Official UK Biography of Attlee.

•July 29 The Japanese government rejects the Potsdam Declaration surrender demand.

Just after midnight, the Indianapolis is struck by a Japanese torpedo.

•July 30 Torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, the Indianapolis sinks in twelve minutes. Between 800 and 900 of the crew of nearly 1,200 are plunged into the shark-infested waters.

“What followed was an ordeal of hell on earth for those who survived the sinking. For a whole host of reasons, many related to the secrecy of her atom bomb mission, the rest of the Navy did not know that Indianapolis was missing.”

— Sam Cox (Rear Adm., USN, Ret.), “Lest We Forget: USS Indianapolis and her sailors” (inactive link)

–Read “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis” via the National Archives including a film clip from the classic scene in Jaws in which Captain Quint describes the sinking of the ship and the shark attacks that followed.

•July 31 The assembly of the atomic bomb, code named “Little Boy,” is completed. The final arming of the bomb will be done in-flight.

In Potsdam, Truman is notified of the bomb being ready. He writes a message that concludes:

“Release when ready, but not sooner than August 2. HST”

According to the Truman Library:

The actual reply that President Truman wrote on July 31, 1945 (Photo taken by Dawn Wilson at the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library)

“No known written record exists in which Harry Truman explicitly ordered the use of atomic weapons against Japan. The closest thing to such a document is this handwritten order, addressed to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, in which Truman authorized the release of a public statement about the use of the bomb. It was written on July 31, 1945 while Truman was attending the Potsdam Conference in Germany. In effect, this served as final authorization for the employment of the atomic bomb, though the expression ‘release when ready’ refers to the public statement.”

Source: Truman Library

•August 1 The atomic bomb is ready and flight orders are prepared. But weather delays the mission. Of four potential target cities, Hiroshima is chosen as the primary target.

In Potsdam that day, the Big Three wrap up their meetings and discuss plans for the trials of war criminals that later become known as the Nuremberg Trials.

Read my 2021 post on the Nuremberg Trials.

In the Pacific, hundreds of survivors from the Indianapolis desperately try to stay afloat in the shark-infested waters.

“In that clear water you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down.” – Survivor of the Indianapolis sinking to the BBC.

•August 2

The Big Three at the end of the Potsdam Conference: Front row (Left to Right) Prime Minister Attlee, President Truman, Generalissimo Stalin. Source: Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

Shortly after midnight, the Potsdam Conference concludes with a joint communique. It includes reference to the United Nations, whose organization and charter had been completed on June 26 at a conference in San Francisco.

Truman speaks of a future Washington meeting with the Soviet leader, but he and Stalin never meet again.

What was clear was that the Conference had solidified the Soviet Union’s domination over much of Eastern Europe, including the eastern half of a divided Germany. Admiral William D. Leahy, Truman’s Chief of Staff, later wrote:

“The Soviet Union emerged at this time as the unquestioned all-powerful influence in Europe….”

The U.S. Navy is still unaware that the Indianapolis has gone down. More than 800 men went into the water and the survivors are spotted by a reconnaissance plane four days after the sinking.

“Marks’s crew dropped rubber rafts and supplies as they witnessed continuing shark attacks. Disregarding orders not to land at sea, the pilot touched down and began taxiing to pick up survivors.

As darkness set in, and as Marks waited for rescue vessels, he pulled men from the water into his aircraft. When the plane’s fuselage was at maximum capacity, survivors were tied to the wings with parachute cord. The pilot and his crew rescued a total of 56 men. Once signaled, a total of seven Navy ships converged on the site and rescued the remaining men. Only 317 sailors survived.” –National Archives, “The Sinking of the USS Indianapolis”

“Looking for a scapegoat, the US Navy placed responsibility for the disaster on Captain McVay, who was among the few who managed to survive. For years he received hate mail, and in 1968 he took his own life. The surviving crew, including Cox, campaigned for decades to have their captain exonerated – which he was, more than 50 years after the sinking.” —“USS Indianapolis Sinking,” BBC

The commander of the Indianapolis, Charles B. McVay III, was the only World War II U.S. Navy captain to be court-martialed for the sinking of his ship. McVay died by suicide in 1968. In 2001, he was exonerated by an act of Congress.

•August 4 Colonel Paul Tibbets briefs the men of the 509th Composite Group -the weapon delivery arm of the Manhattan Project. Tibbets is the commander of the unit. His men do not know the nature of the bomb they will carry.

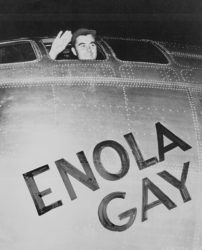

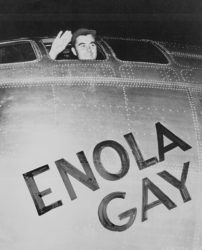

•August 5 The bombing mission is confirmed and Colonel Paul Tibbets announces he will pilot the plane which he names “Enola Gay,” after his mother.

Colonel Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., Pilot of the Enola Gay, the Plane that Dropped the Atomic Bomb August 6, 1945 (National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535737)

•August 6 At 0245 local time on Tinian,

“Enola Gay begins takeoff roll. [Pilot] Colonel Paul Tibbets says to co-pilot Robet Lewis, ‘Let’s go.’ He pushes all of the throttles forward. The overloaded Enola Gay lifts slowly into the night sky, using all of the more than two miles of runway.”

—Atomic Heritage Foundation, minute-by-minute timeline of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

0730:

“Tibbets announces to the crew: ‘We are carrying the world’s first atomic bomb.’ He pressurizes the Enola Gay and begins an ascent to 32,700 feet. The crew puts on their parachutes and flak suits.”

0912: Control of the Enola Gay is handed over to the bombardier, Thomas Ferebee, as the bomb run begins. A Radio Hiroshima operator reports that three planes have been spotted.

0914 (0814 Hiroshima time): Tibbets tells his crew, “On glasses.”

–Atomic Heritage Foundation Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing Timeline

8:15 AM (Hiroshima local time) The first atomic bomb is detonated over Hiroshima.

“In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.”

Source: Hiroshima

The atomic bomb cloud over Hiroshima Source: National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/542192

and Nagasaki Remembered.

“In the street, the first thing he saw was a squad of soldiers who had been burrowing into the hillside opposite, making one of the thousands of dugouts in which the Japanese apparently intended to resist invasion, hill by hill, life for life; the soldiers were coming out of the hole, where they should have been safe, and blood was running from their heads, chests, and backs. They were silent and dazed.

Under what seemed to be a local dust cloud, the day grew darker and darker.”

–John Hersey, “Hiroshima,” New Yorker (August 24, 1946)

In Hiroshima, the estimated death toll reaches eighty thousand people killed instantly; as many as 90 percent of the city’s nurses and doctors also die instantly. By 1950, as many as 200,000 die as a result of long-term effects of radiation.

“Historians say General Groves understood the radiation issue as early as 1943 but kept it so compartmentalized that it was poorly known by top American officials, including Harry S. Truman. At the time he authorized the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman, scholars say, knew almost nothing of the bomb’s radiation effects.”

Read: “The Black Reporter Who Exposed a Lie about the Atomic Bomb” New York Times

In his official announcement, President Truman said,

It was to spare the Japanese people from utter destruction that the ultimatum of July 26 was issued at Potsdam. Their leaders promptly rejected that ultimatum. If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth. Behind this air attack will follow sea and land forces in such numbers and power as they have not yet seen and with the fighting skill of which they are already well aware.

Aftermath of atomic bomb-November 1945 (Image: US Dept. of Energy”

Read Don’t Know Much About Hiroshima for more details about the bombing and its aftermath.

•August 7 A report to the Japanese Imperial Army General Staff reads:

“The whole city of Hiroshima was destroyed instantly by a single bomb.” (Atomic Heritage Foundation)

On Guam, the decision to use a second device is made and the mission date set for August 10, then moved to August 9 over weather concerns.

Fat Man being lowered and checked on transport dolly for airfield trip Image Source: Heritage Foundation https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/little-boy-and-fat-man

•August 8 Fulfilling a pledge Stalin had made earlier at the Yalta conference, the Soviet Union declares war on Japan and invades Manchuria the next day, sending more than one million troops into Japanese-held territory.

The Japanese military leadership was still divided over the surrender demand, with some leading generals vowing to fight to the death. A coup against Emperor Hirohito began to be planned by members of the Japanese military.

A plutonium bomb code named “Fat Man” is prepared on Tinian. It will be carried by a B-29 called “Bockscar.” The primary target is the city of Kokura, home to a large munitions plant.

•August 9

0347: Bockscar, piloted by Major Charles Sweeney, lifts off from Tinian Island. The target of choice is Kokura Arsenal.

Clouds and smoke from nearby fires obscure Kokura, so “Fat Man” is dropped over the secondary target, the city of Nagasaki, with a population estimated at 263,000, a city that was home to two Mitsubishi military plants. It is also the site of a prisoner of war camp.

“Nagasaki was a city on the west coast of Kyushu on picturesque Nagasaki Bay. It was famous as the setting for Puccini’s beautiful opera Madame Butterfly. It was also home to two huge Mitsubishi war plants on the Urakami River. This complex was the primary target, but because the city was built in hilly, almost mountainous terrain, it was a much more difficult target than Hiroshima…

Image: “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered”

Fat Man exploded at 1,840 feet above Nagasaki and approximately 500 feet south of the Mitsubishi Steel and Armament Works with an estimated force of 22,000 tons of TNT.

Unlike Hiroshima, there was no firestorm at Nagasaki. Despite this, the blast was more destructive to the immediate area, due to the topography and the greater power of Fat Man.”

—Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

The death toll in Nagasaki also reaches 80,000 by the end of 1945. Read a full account of this mission in “Nagasaki: The Last Bomb” by Alex Wellerstein (New Yorker, August 7, 2015)

The National Archives “Unwritten Record” blog also offers resources on the atomic bombings.

Read this piece from Scientific America (August 6, 2023) about the American plan to study the effects of the atomic bombs

“On November 26, 1946, President Harry Truman authorized the National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council to establish the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) ‘to undertake long range, continuing study of the biological and medical effects of the atomic bomb on man.'”– “Hiroshima’s Anniversary Marks An Injustice Done to Blast Survivors.“

•August 10 After Nagasaki is bombed, Truman orders no more strikes without his authorization. Another plutonium core for a third weapon is prepared for shipment.

September 24, 1945, 6 weeks after Nagasaki was destroyed by the world’s second atomic bomb attack. Photo by Cpl. Lynn P. Walker, Jr. (USMC) National Archives FILE #: 127-N-136176

Although an unofficial surrender message was sent by a Japanese news agency, the Japanese cabinet was divided and no decision was made. The Emperor would not surrender his sovereignty.

•August 11 The U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes rejects any conditional surrender and states that the Emperor and Japan’s government will be subject to the Allied Powers and declares that any future Japanese government must reflect the will of the people.

Soviet troops invade South Sakhalin island, Japanese-held territory.

•August 12-13 Soviet troops advance into the Korean peninsula.

Emperor Hirohito agrees to accept the terms of Secretary Byrnes’s note and orders the suspension of military activity. He records a surrender announcement. Military officers began to plot against Hirohito in a coup known as the “Kyujo incident.”

•August 13 The bombing of Japan, including firebombing, resumes with more than 1,000 B-29s taking part.

Residential section of Tokyo after the March 1945 air raids. (Wikimedia commons http://www.kmine.sakura.ne.jp/kusyu/kuusyu.html/

Japanese officers continue to seek allies in their planned coup against the Imperial government.

•August 14 (August 15 in Japan): The military coup fails and several plotters commit suicide.

In an extraordinary address recorded earlier, the Emperor of Japan is heard on the radio for the first time and accepts the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration, agreeing to the unconditional surrender.

Read: “The Emperor’s Speech” by Max Fisher (The Atlantic, August 15, 2012)

At a White House conference, according to United Press International, Truman says:

“This is the day when Fascist and police governments cease to exist in the world. This is the day for democracy.”

-Source: “Japan Surrenders Unconditionally, World At Peace” UPI archives

“Japan surrendered unconditionally tonight, bringing peace to the world after the bloodiest conflict mankind has known.” (UPI Archives)

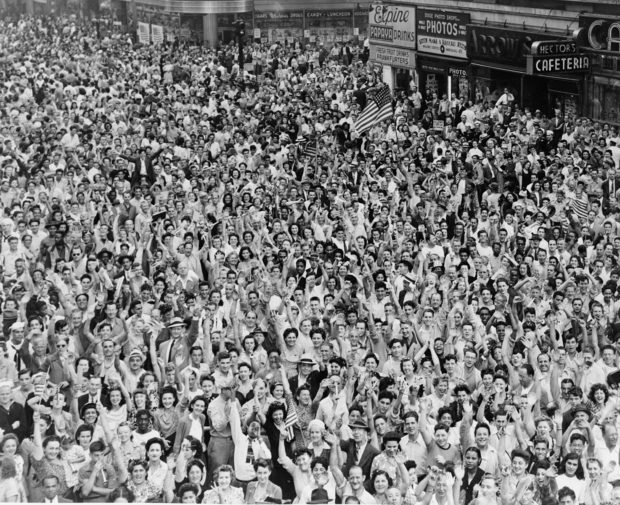

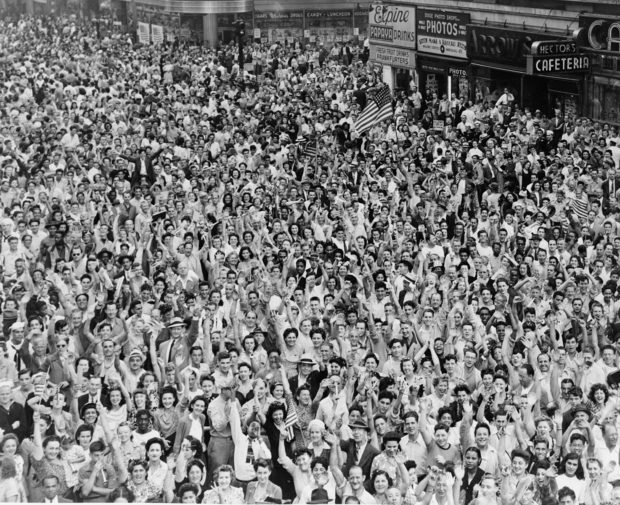

Across America and England, jubilant crowds fill the streets once more for an unofficial V-J (Victory over Japan) Day, as they had three months earlier on VE Day, May 8,1945, after Germany’s surrender ended the war in Europe.

A video clip of Truman’s August 14 announcement from C-Span.

V-J Day Times Square August 14, 1945 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c19650

•September 2, 1945 A formal surrender ceremony is performed in Tokyo Bay and that date is also referred to as V-J Day.

Formal surrender aboard USS Missouri Sept. 2. 1945 https://www.history.navy.mil/our-collections/photography/us-navy-ships/battleships/missouri-bb-63/USA-C-2719.html

Almost since the day the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, critics have second-guessed Truman’s decision and motives. A generation of historians and commentators have defended or repudiated the need for unleashing the atomic weapon. Admiral William D. Leahy, who was with Truman at Potsdam, later wrote in a memoir:

Once it had been tested, President Truman faced the decision as to whether to use it. He did not like the idea, but he was persuaded that it would shorten the war against Japan and save American lives. It is my opinion that the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan.

–William D. Leahy, I Was There (1950)

On the same day, in colonial French Indochina, Ho Chi Minh –who had been supported by the American OSS in its fight against Japan– declared Vietnam’s independence from France. On the occasion, Ho Chi Minh cited Thomas Jefferson:

All men are created equal. They are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among them are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

-Source: Council on Foreign Relations

In China, however, the Japanese surrender ended the wartime alliance between the Communists and Nationalists. The Chinese civil war began anew, with the US supporting Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Stalin’s USSR backing Mao Zedong’s Communists.

Read about Mao’s rise to power in Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy.

Many historians contend that preventing death and casualties in an invasion of Japan was only a partial explanation for the use of the two atomic bombs. The United States was already wary of Stalin and his designs on Japan’s wartime territory. They argue that the use of the two devices was meant to end the war quickly to prevent Stalin from capturing territory held by Japan. It may have also been a signal to Stalin and the Soviet Union that the United States possessed these weapons and was willing to use them.

In other words, the dropping of the atomic bombs became the first volley in the Cold War.

READ about the debate in this Smithsonian article.

In 1952, Albert Einstein –whose 1939 letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt had set the Manhattan Project in motion — wrote a brief essay published by a Japanese magazine Kaizo in which he stated:

I was well aware of the dreadful danger for all mankind, if these experiments would succeed. But the probability that the Germans might work on that very problem with good chance of success prompted me to take that step. I did not see any other way out, although I always was a convinced pacifist. To kill in war time, it seems to me, is in no ways better than common murder.

He concluded:

Gandhi, the greatest political genius of our time has shown the way, and has demonstrated the sacrifices man is willing to bring if only he has found the right way. His work for the liberation of India is a living example that man’s will, sustained by an indomitable conviction is stronger than apparently invincible material power.

–Source Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered

You can read more about Hiroshima and the dropping of the atomic bombs in Don’t Know Much About History and more about President Truman in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and in The Hidden History of America At War. Read more about Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin in STRONGMAN published on October 6, 2020.