Abraham Lincoln died on April 15, 1865. He had been begun his second term a few weeks before.

On March 4, 1865, Abraham Lincoln delivered his second inaugural address. Just 701 words long, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address took only six or seven minutes to deliver. And yes, it is the greatest American speech.

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Source and Complete Text: The Avalon Project

At a White House reception, President Lincoln encountered Frederick Douglass. “I saw you in the crowd today, listening to my inaugural address,” the president remarked. “How did you like it?” “Mr. Lincoln,” Douglass answered, “that was a sacred effort.” (Source: Gilder Lehman Institute of American History)

“The Martyr of Liberty” via Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/item/scsm000402/

On April 15, 1865 –weeks after he delivered that address– Lincoln died at the hand of assassin John Wilkes Booth.

(Linked resources via Library of Congress)

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

“Eli Whitney,” portrait of the inventor, oil on canvas, by the American painter Samuel F. B. Morse. 35 7/8 in. x 27 3/4 in. Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

On March 14, 1794, Eli Whitney received a patent for the machine known as the Cotton Gin. Here is a short video about the Connecticut-born inventor’s most famous “invention,” the Cotton Gin. This was created as my first contribution to Ted-Ed: “Lessons Worth Sharing.”

This portrait of the inventor is by another inventor– Samuel F.B. Morse who was a well-known painter and art teacher before he gained fame for the development of the telegraph and the Morse Code.

The cotton gin changed history for good and bad. By allowing one field hand to do the work of 10, it powered a new industry that brought wealth and power to the American South — but, tragically, it also multiplied and prolonged the use of slave labor. In this video, I discuss innovation, while warning of unintended consequences.

Eli Whitney died in New Haven, Connecticut on January 8, 1825. You can learn more about Whitney and his inventions at the Eli Whitney Museum and Workshop.

Read more about the history and impact of American slavery in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the Civil War and my forthcoming book In The Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Five Black Lives. (Holt Books, Sept. 20, 2016)

(Post revised 2/19/2022)

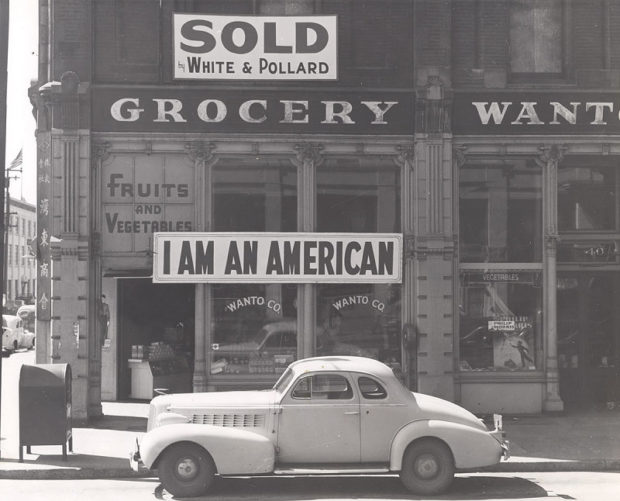

Eighty years ago, on this date- February 19, 1942 – a different kind of infamy

“The Masuda family, owners of the Wanto Grocery in Oakland, California, proclaimed that they were American, even as they were forced to sell their business before they were incarcerated in August 1942.” National Museum of American History. Photo by Dorothea Lange (Source: National Archives)

Franklin D. Roosevelt famously told Americans when he was inaugurated in 1933:

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.

But on February 19, 1942 –a little more than two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor— President Roosevelt allowed America’s fear to provoke him into an action regarded among his worst mistakes. He issued Executive Order 9066.

It declared certain areas to be “exclusion zones” from which the military could remove anyone for security reasons. It provided the legal groundwork for the eventual relocation of approximately 120,000 people to a variety of detention centers —“internment camps” — around the country, the largest forced relocation in American history. Nearly two-thirds of them were American citizens.

The attitude of many Americans at the time was expressed in a Los Angeles Times editorial of the period:

“A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched… So, a Japanese American born of Japanese parents, nurtured upon Japanese traditions, living in a transplanted Japanese atmosphere… notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American…” (Source: Impounded, p. 53)

On March 23, 1942, the United States government began taking away the liberty of more than one hundred thousand people–the Japanese Americans viewed as a threat after Pearl Harbor. On that date, the U.S. Army began removing people of Japanese descent from Los Angeles. (Smaller numbers of Americans of German and Italian descent were also detained.)

See this exhibit on Internment from the National Museum of American History.

Some of the most famous photographs of the period were taken by Dorothea Lange. Read this piece from the National Archives. The FDR Library and Museum offers resources on teaching Executive Order 9066 and photographer Ansel Adams also documented the period.

Roy Takano [i.e., Takeno] at town hall meeting, Manzanar Relocation Center, California Photo by Ansel Adams Source: Library of Congress

[Originally posted December 2020; revised 1/29/2022]

Thomas Paine was born in England on January 29, 1736 (in the Old Style; his birth-date is also listed as February 9, 1737 in the New Style).

“These are the times that try men’s souls…. Tyranny, like hell is not easily conquered.”

–Thomas Paine, The American Crisis (December 19, 1776)

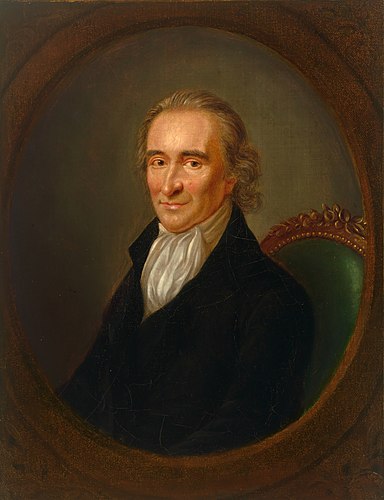

Thomas Paine ©National Portrait Gallery London copy by Auguste Millière, after an engraving by William Sharp, after George Romney oil on canvas, circa 1876

Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

-Thomas Paine Common Sense

Thomas Paine’s essay Common Sense is widely credited with helping to rouse Americans to the patriot cause. Its sales were extraordinary at the time; given today’s American population, current day sales would reach some 60 million copies.

Common sense; addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting subjects (Library of Congress)

The pamphleteering Paine is best known for Common Sense, which appeared in January 1776 and The Crisis — first published on December 19 1776 — among other works that supported the cause of independence. But after the Revolution, Paine returned to his native England and later went to France, then in the throes of its Revolution.

Paine was caught up in the complex politics of the bloody Revolution there, eventually winding up in a French prison cell, facing the prospect of the guillotine. After eventually being freed, Paine wrote an open letter in 1796 angrily denouncing President George Washington for failing to do enough to secure his release.

“Monopolies of every kind marked your administration almost in the moment of its commencement. The lands obtained by the Revolution were lavished upon partisans; the interest of the disbanded soldier was sold to the speculator…In what fraudulent light must Mr. Washington’s character appear in the world, when his declarations and his conduct are compared together!”

Source: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

This was a serious case of bridge-burning and Paine swiftly fell from grace in America. But apart from dissing the Father of the Country, Paine had also fallen from favor for his most famous work after Common Sense. In 1794, he had published The Age of Reason (Part I), a deist assault on organized religion and the errors of the Bible.

In it, Paine had written:

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.

All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

(Source: USHistory.org)

After returning to the United States, which owed so much to him, Paine was regarded as an atheist and was abandoned by most of his friends and former allies. He died in disgrace, an outcast from the United States he had helped create. The Quaker church he had rejected refused to bury him after he died in Greenwich Village (New York City) in 1809. He was buried on his farm in New Rochelle, New York. A handful of people attended his funeral.

An admirer brought his remains back to England for reburial there, but they were lost.

Today he is honored in New York City by a small park named in his honor.

“This park in the heart of New York City’s civic center is named for patriot, author, humanitarian, and political visionary Thomas Paine (1737-1809). The land that is now Thomas Paine Park was once part of a freshwater swamp surrounded, ironically, by three former British prisons for revolutionaries.

His most famous work, Rights of Man (1791), was written after the French Revolution and proposes that government is responsible for protecting the natural rights of its people. Many of Paine’s ideas were strikingly far sighted. He advocated for the abolition of slavery, defended freedom of thought and expression, and proposed an association of nations to avert the spread of conflicts.”

You can read more about Thomas Paine, his relationship with Washington and his ultimate fate in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

(Originally posted 1/10/2012; revised 1/10/2022)

Society in every state is a blessing, but Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one.

–Thomas Paine, January 10, 1776

Image Library of Congress Thomas Paine (1737–1809). Common Sense. Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1776. American Imprint Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (003.00.00) //www.loc.gov/exhibits/books-that-shaped-america/1750-1800/Assets/ba0003_enlarge.jpg

You know that saying about the pen being mightier than the sword? As the American Revolution haltingly began, an anonymous writer helped prove it true.

The battles at Lexington and Concord in 1775, the easy victory at Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775, and the devastating casualties inflicted on the British army by the rebels at Bunker (Breed’s) Hill in June 1775 had all given hope to the patriot cause a full year before independence was declared.

But the final break—Independence—still seemed too extreme to some. It’s important to remember that the vast majority of Americans at the time were first and second generation. Their family ties and their sense of culture and national identity were essentially English. Many Americans had friends and family in England. And the commercial ties between the two were obviously also powerful.

The forces pushing toward independence needed momentum, and they got it in several ways. The first factor was another round of heavy-handed British miscalculations. First, the king issued a proclamation cutting off the colonies from trade. Then, unable to conscript sufficient troops, the British command decided to supplement its regulars with mercenaries, soldiers from the German principalities sold into King George’s service by their princes. Most came from Hesse-Cassel, so the name Hessian became generic for all of these hired soldiers.

The Hessians accounted for as much as a third of the English forces fighting in the colonies. Their reputation as fierce fighters was linked to a frightening image—reinforced, no doubt, by the British command—as plundering rapists. (Ironically, many of them stayed on in America. Benjamin Franklin gave George Washington printed promises of free land to lure mercenaries away from English ranks.) When word of the coming of 12,000 Hessian troops reached America, it was a shock, and further narrowed chances for reconciliation. In response, a convention in Virginia instructed its delegates to Congress to declare the United Colonies free and independent.

The second factor was a literary one. On January 10, 1776, an anonymous pamphlet entitled Common Sense came off the presses of a patriot printer. Its author, Thomas Paine, had simply, eloquently, and admittedly with some melodramatic prose, stated the reasons for independence. He reduced the hereditary succession of kings to an absurdity, slashed down all arguments for reconciliation with England, argued the economic benefits of independence, and even presented a cost analysis for creating an American navy.

With the assistance of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine had come to America from London and found work with a Philadelphia bookseller. In the colonies for only a few months, Paine wrote, at Franklin’s suggestion, a brief history of the upheaval against England.

Thomas Paine (National Portrait Gallery: NPG.2008.5)

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the impact and importance of Common Sense. Paine’s polemic was read by everyone in Congress, including General Washington, who commented on its effects on his men. Equally important, it was read by people everywhere. The pamphlet quickly sold 150,000 copies, going through numerous printings until it had reached half a million. (Approximating the American population at the time, including slaves, at 3 million, a current equivalent pamphlet would have to sell more than 35 million copies!) Paine donated the proceeds to Washington’s army.

For the first time, mass public opinion had swung toward the cause of independence.

Adapted from Don’t Know Much About History which discusses the Revolution and Thomas Paine’s unhappy fate. In Paris during the French Revolution, Paine was imprisoned by revolutionary authorities. Upon his eventual release, he wrote an angry open letter to his old comrade George Washington, in which he skewered Washington for not having done enough to secure his release from the French prison. Paine later returned to America but when he died in 1809, no church in American would accept his body for burial as he was an atheist. The man who influenced history Paine was buried with a handful of people in attendance at his farm in New Rochelle, New York. His remains were then removed to his native England for reburial but were later lost.

(Originally posted August 19, 2021; reposting on 1/4/2022 as we near the first anniversary of the Capitol Insurrection)

Whose history is it? Who gets to tell it? And whose truth ends up in schoolbooks?

I pondered these questions after hearing President Biden address the recent ceremony honoring the police officers who defended the Capitol on January 6, 2021. During the event, the president said:

“The tragedy of that day deserves the truth above all else. We cannot allow history to be rewritten. We cannot allow the heroism of these officers to be forgotten. We have to understand what happened — the honest and unvarnished truth. We have to face it. That’s what great nations do.”

President Biden’s words recalled something another president articulated five years earlier:

“A great Nation does not hide its history; it faces its flaws and corrects them. This museum tells the truth: that a country founded on the promise of liberty held millions in chains…that the price of our Union was America’s original sin.”

—George W. Bush in dedicating the National Museum of African American History and Culture (9/24/2016)

At this moment, the United States is in a war over who gets to tell two pieces of history with extraordinary relevance and resonance. The story of the January 6 insurrection to overturn an election and subvert American democracy at the behest of a defeated president is one of these battles for history.

[Read and watch the New York Times video account of the events of January 6.]

“The visual investigation, ‘Day of Rage,’ which was published digitally on June 30 and which is part of a print special section in Sunday’s paper [August 15, 2021], comes as conservative lawmakers continue to minimize or deny the violence, even going as far as recasting the riot as a ‘normal tourist visit.’”

The other is the titanic, racially-charged struggle over how we teach our children, and ourselves, about the country’s “original sin” – the Great Contradiction that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles. That is no “theory” but a powerful thread of facts, events, and documents that course through the nation’s historical fabric.

Read: “The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles,” my article on teaching and talking abut slavery in U.S. History in Social Education (March/April 2020)

That “winners write history” is a well-worn adage. The United States has clearly had its share of a history composed largely by one group of winners. They were white, Anglo men who threaded together a proud, patriotic tale of the birth of a nation. It dropped a great many stitches. It was for that reason that Founder John Adams would write,

“The history of our country will be one continued lie from one end to the other. The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington.”

Adams was not far off. For much of the nation’s existence, its narrative has been crafted into a tidy legend by men who helped create the shibboleth now called “American Exceptionalism.”

The United States has no monopoly on the desire to promulgate a blemish-free narrative of its past. In Italy, Mussolini once said,

“Our myth is the Nation, our myth is the greatness of the Nation! And to this myth, to this grandeur, that we wish to translate into a complete reality, we subordinate all the rest.”

–From Herman Finer, Mussolini’s Italy (1935), p. 218; quoted in Franklin Le Van Baumer, ed., Main Currents of Western Thought (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), p.748.

The Soviet Union was notorious for its vanishing generals – men wiped from Kremlin photographs following each Stalinist purge. Japan balks at any mention of its wartime atrocities, including the mistreatment of captive Korean “comfort women.” And as China celebrated one hundred years of the Communist Party, the erasure of such events as mass starvation and the Tiananmen Square massacre is complete.

Read “Democracy is not a spectator sport,” my article published in Social Education (September 2019 issue)

One notable exception has been Germany, where Holocaust studies including visits to concentration camp sites are mandatory in high school. On the other hand, it is worth noting that right-wing nationalist groups have been pushing back on the requirement. In Germany, writes The Atlantic’s Emily Schulthies, leaders of Alternative for Germany, a right-wing party, “have sought to diminish the importance of the Nazi era to produce an argument for renewed national pride: The party’s co-leader Alexander Gauland referred to it as a ‘speck of bird poop’ in Germany’s otherwise admirable history….” (The Atlantic, April 10, 2019)

Of course, the man who understood the control of history better than anyone was George Orwell.

“When one knew that any document was due for destruction, it was an automatic action to lift the flap of the nearest memory hole and drop it in, whereupon it would be whirled away on a current of warm air to the enormous furnaces….

–George Orwell, 1984 (p. 35)

Orwell’s “memory hole” demonstrated the unconstrained power of the Party to shape both history and language. It is a lesson on display at this moment –not in darkened corridors but in broad daylight as January 6 has emerged in some accounts as an ordinary tourist day and America’s racist past is buried by state legislators who can’t stand the truth.

Strongmen and dictators of every stripe understand the central importance of Orwell’s “memory hole.” Tyrants know how to destroy a set of facts and create new ones –the “Big Lie” that demands complete submission. As Mussolini’s Fascist creed put it: “Believe Obey Fight.”

While part of the historian’s work is to recover and restore the true record of what happened, the facts should never be consigned to the memory hole’s furnace in the first place. Replacing truth with “Big Lie” partisan narratives or indoctrination sessions is the devious work of propaganda meant to sway people to “Believe” and “Obey.”

Instead, we must stay vigilant, dedicated to Truth. That, after all, is what sets us free.

© 2021, 2022 Copyright Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

The 2021 Winter Solstice arrives on December 21 at 10:59 am EST. Thus saith the Farmer’s Almanac.

So ’tis a perfect day to talk about the real “reason for the season.”

Here’s the real first Christmas question: Why all the fuss over December 25?

For starters, the Gospels never mention a precise date or even a season for the birth of Jesus. How then did we settle on December 25 and all those festive lights?

If a bright light just went off in your head, you’re getting warm. It is largely about the Sun.

In ancient times, a popular Roman festival celebrated Saturnalia, a Thanksgiving-like holiday marking the winter solstice and honoring Saturn, the god of agriculture. The Saturnalia began on December 17th and while it only lasted two days at first, it was eventually extended into a weeklong period that lost its agricultural significance and simply became a time of general merriment. Even slaves were given temporary freedom to do as they pleased, while the Romans feasted, visited one another, lit candles and gave gifts. Later it was changed to honor the official Roman Sun god known as Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) and the solstice fell on December 25.

Two other important pagan gods popular in ancient Rome were also celebrated around this date. The Romans were big on adopting the gods of the people they conquered. Mithra, a Persian god of light who was first popular among Roman soldiers, acquired a large cult in ancient Rome. The birth of Attis, another agricultural god from Asia Minor, was also celebrated on December 25. Attis dies but is brought back to life by his lover, a goddess whose temple later became the site of an important basilica honoring the Virgin Mary. By the way, the symbol of Attis was a pine tree.

In northern Europe, the solstice was celebrated with the burning of the “Yule” log. “Yule” meant wheel. It was the wheel of the chariot of Odin bringing the sun –another dead god being revived– back to life.

Candles. Gift giving. Pine trees. Dying gods brought back to life. Hmmm. Sound familiar?

All the similarities between Saturnalia and these other Roman holidays and the celebration of Christmas are no coincidence. In the fourth century, Pope Julius 1 assigned December 25 as the day to celebrate the Mass of Christ’s birth –Christ’s mass. This was a clever marketing ploy that conveniently sidestepped the problem of eliminating an already popular holiday while converting the population.

As Christianity moved into northern Europe, the Norse myths were also repurposed to tell the Christ story.

There is a scholarly argument that the December 25 date was marked earlier in some Christian communities, as argued by Yale Divinity school Dean Andrew McGowan. But the official recognition by the Pope cemented the date for many Christians. In other Christian communities, January 6 — the Epiphany or the day the magi visited the infant Jesus– was considered more significant. The period between these dates also accounts for the “Twelve Days of Christmas.” Other authorities disagree and say that December date was arrived at by adding nine months to March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation, the day of Jesus’s miraculous conception.

But most modern Christmas traditions reflect the merger of pagan rituals, beliefs, and traditions with Christianity. The early church fathers knew that they couldn’t convert people without allowing them to keep some of their ancient festivals and rituals so they would allow them if they could be connected to Christianity.

The importance of the winter solstice, then, is crucial to understanding many of the other traditions of this season. Evergreen trees, mistletoe, holly, and Yule logs all relate back to pre-Christian practices and symbols that celebrate the return of light and life after the Solstice. That’s why the Puritans rejected Christmas celebrations under Cromwell and in the Massachusetts colony in 1659.

Yale Professor Bruce Gordon writes:

“The Puritans sought to turn Christmas into a fast day, with an act of Parliament in 1643 declaring that it should be observed ‘with the more solemn humiliation because it may call to remembrance our sins, and the sins of our forefathers who have turned this Feast, pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him, by giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights.’ Two years later, the Directory of Public Worship was unequivocal that feasts such as Christmas had no warrant in scripture. The attack on Christmas in England was sustained, fierce, hugely divisive, and ultimately a failure. The festival was restored under Charles II in 1660 to much public acclaim.

North of the Scottish border, when Christmas was abolished by Parliament in 1640 it was declared that ‘The kirke within this kingdome is now purged of all superstitious observatione of dayes.’ The legacy lasted almost four hundred years, and Christmas was not restored as a public holiday in Scotland until 1958, remaining to this day very much in the shadow of Hogmanay (New Year). Across the Atlantic, the Puritans of New England demonstrated their contempt for Christmas festivities by ensuring that the day was filled with godly labor.”

Read my post Who Started the War on Christmas?”

While we are talking about dates, the precise year of the birth of Jesus is also a mystery. The dating system we use is based on a system devised by a monk around 1500 years ago and is seriously flawed. The historical King Herod who ordered the massacre of the innocents died in 4 BC (or BCE, Before the Common Era). The “census” ordered by Emperor Augustine is not recorded in Roman history, but a local census did take place in the Roman province of Judea in 6 AD (or CE, the Common Era). Is that all perfectly clear now?

You can read more about the mythic roots of Christmas and the gospel accounts of Jesus in Don’t Know Much About Mythology and Don’t Know Much About® the Bible.

(Originally posted in June 2015; updated December 4, 2021)

On December 4, 1783, General George Washington bid farewell to his troops at the historic Fraunces Tavern Museum in Lower Manhattan.

In 2015, I spoke there about my book THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah.

The event was filmed by C-Span and can be seen here. The book includes a chapter about the battle of Yorktown.

Read more about these events in…

(Video directed and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2015)

When I was a kid in the early 1960s, the autumn social calendar was highlighted by the Halloween party in our church. In these simpler day, the kids all bobbed for apples and paraded through a spooky “haunted house” in homemade costumes –Daniel Boone replete with coonskin caps for the boys; tiaras and fairy princess wands for the girls. It was safe, secure and innocent.

The irony is that our church was a Congregational church — founded by the Puritans of New England. The same people who brought you the Salem Witch Trials.

Here’s a link to a history of those Witch Trials in 1692.

Rooted in pagan traditions more than 2000 years old, Halloween grew out of a Celtic Druid celebration that marked summer’s end. Called Samhain (pronounced sow-in or sow-een), it combined the Celts’ harvest and New Year festivals, held in late October and early November by people in what is now Ireland, Great Britain and elsewhere in Europe. This ancient Druid rite was tied to the seasonal cycles of life and death — as the last crops were harvested, the final apples picked and livestock brought in for winter stables or slaughter. Contrary to what some modern critics believe, Samhain was not the name of a malevolent Celtic deity but meant, “end of summer.”

The Celts also saw Samhain as a fearful time, when the barrier between the worlds of living and dead broke, and spirits walked the earth, causing mischief. Going door to door, children collected wood for a sacred bonfire that provided light against the growing darkness, and villagers gathered to burn crops in honor of their agricultural gods. During this fiery festival, the Celts wore masks, often made of animal heads and skins, hoping to frighten off wandering spirits. As the celebration ended, families carried home embers from the communal fire to re-light their hearth fires.

Getting the picture? Costumes, “trick or treat” and Jack-o-lanterns all got started more than two thousand years ago at an Irish bonfire.

Christianity took a dim view of these “heathen” rites. Attempting to replace the Druid festival of the dead with a church-approved holiday, the seventh-century Pope Boniface IV designated November 1 as All Saints’ Day to honor saints and martyrs. Then in 1000 AD, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to remember the departed and pray for their souls. Together, the three celebrations –All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls Day– were called Hallowmas, and the night before came to be called All-hallows Evening, eventually shortened to “Halloween.”

And when millions of Irish and other Europeans emigrated to America, they carried along their traditions. The age-old practice of carrying home embers in a hollowed-out turnip still burns strong. In an Irish folk tale, a man named Stingy Jack once escaped the devil with one of these turnip lanterns. When the Irish came to America, Jack’s turnip was exchanged for the more easily carved pumpkin and Stingy Jack’s name lives on in “Jack-o-lantern.”

Halloween, in other words, is deeply rooted in myths –ancient stories that explain the seasons and the mysteries of life and death.

You can read more about ancient myths in the modern world in Don’t Know Much About Mythology and more about the Salem Witch Trials in Don’t Know Much About History.

Answer: Roger Williams, the dissident minister banished by the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony on October 9, 1635. Williams was told to leave the colony within six weeks. If he returned, he risked execution. He eventually went on to found Rhode Island, with a written constitution guaranteeing freedom of religion, approved by Parliament in 1644.

Williams died in Rhode Island in 1683. Learn more at the Roger Williams National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).

As Williams biographer John M. Barry wrote:

Williams described the true church as a magnificent garden, unsullied and pure, resonant of Eden. The world he described as “the Wilderness,” a word with personal resonance for him. Then he used for the first time a phrase he would use again, a phrase that although not commonly attributed to him has echoed through American history. “[W]hen they have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wildernes of the world,” he warned, “God hathe ever broke down the wall it selfe, removed the Candlestick, &c. and made his Garden a Wildernesse.”

Read more: “God, Government and Roger Williams’ Big Idea” by John M. Barry in Smithsonian magazine

The phrase, “wall of separation between church and state” does not appear in the United States Constitution as many people think. But it was used in a famous letter written by Thomas Jefferson in 1802.

As I wrote in a 2011 essay, “Why U.S. is Not a Christian Nation,”

The idea was not Jefferson’s. Other 17th- and 18th-century Enlightenment writers had used a variant of it. Earlier still, religious dissident Roger Williams had written in a 1644 letter of a “hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.”

Williams, who founded Rhode Island with a colonial charter that included religious freedom, knew intolerance firsthand. He and other religious dissenters, including Anne Hutchinson, had been banished from neighboring Massachusetts, the “shining city on a hill” where Catholics, Quakers and Baptists were banned under penalty of death.

According to the Library of Congress:

This phrase has become well known because it is considered to explain (many would say, distort) the “religion clause” of the First Amendment to the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion …,” a clause whose meaning has been the subject of passionate dispute for the past 50 years.

Read more about Jefferson’s letter and the phrase: “A Wall of Separation” by James Hutson, a curator at the Library of Congress.

And read more about traditions of tolerance in my article in Smithsonian, “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance.”