(Originally posted 1/10/2012; revised 1/10/2022)

Society in every state is a blessing, but Government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one.

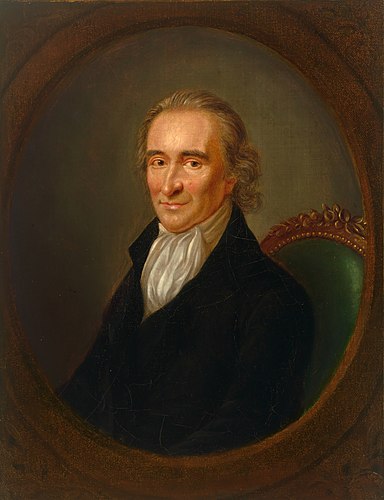

–Thomas Paine, January 10, 1776

Image Library of Congress Thomas Paine (1737–1809). Common Sense. Philadelphia: R. Bell, 1776. American Imprint Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (003.00.00) //www.loc.gov/exhibits/books-that-shaped-america/1750-1800/Assets/ba0003_enlarge.jpg

You know that saying about the pen being mightier than the sword? As the American Revolution haltingly began, an anonymous writer helped prove it true.

The battles at Lexington and Concord in 1775, the easy victory at Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775, and the devastating casualties inflicted on the British army by the rebels at Bunker (Breed’s) Hill in June 1775 had all given hope to the patriot cause a full year before independence was declared.

But the final break—Independence—still seemed too extreme to some. It’s important to remember that the vast majority of Americans at the time were first and second generation. Their family ties and their sense of culture and national identity were essentially English. Many Americans had friends and family in England. And the commercial ties between the two were obviously also powerful.

The forces pushing toward independence needed momentum, and they got it in several ways. The first factor was another round of heavy-handed British miscalculations. First, the king issued a proclamation cutting off the colonies from trade. Then, unable to conscript sufficient troops, the British command decided to supplement its regulars with mercenaries, soldiers from the German principalities sold into King George’s service by their princes. Most came from Hesse-Cassel, so the name Hessian became generic for all of these hired soldiers.

The Hessians accounted for as much as a third of the English forces fighting in the colonies. Their reputation as fierce fighters was linked to a frightening image—reinforced, no doubt, by the British command—as plundering rapists. (Ironically, many of them stayed on in America. Benjamin Franklin gave George Washington printed promises of free land to lure mercenaries away from English ranks.) When word of the coming of 12,000 Hessian troops reached America, it was a shock, and further narrowed chances for reconciliation. In response, a convention in Virginia instructed its delegates to Congress to declare the United Colonies free and independent.

The second factor was a literary one. On January 10, 1776, an anonymous pamphlet entitled Common Sense came off the presses of a patriot printer. Its author, Thomas Paine, had simply, eloquently, and admittedly with some melodramatic prose, stated the reasons for independence. He reduced the hereditary succession of kings to an absurdity, slashed down all arguments for reconciliation with England, argued the economic benefits of independence, and even presented a cost analysis for creating an American navy.

With the assistance of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine had come to America from London and found work with a Philadelphia bookseller. In the colonies for only a few months, Paine wrote, at Franklin’s suggestion, a brief history of the upheaval against England.

Thomas Paine (National Portrait Gallery: NPG.2008.5)

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the impact and importance of Common Sense. Paine’s polemic was read by everyone in Congress, including General Washington, who commented on its effects on his men. Equally important, it was read by people everywhere. The pamphlet quickly sold 150,000 copies, going through numerous printings until it had reached half a million. (Approximating the American population at the time, including slaves, at 3 million, a current equivalent pamphlet would have to sell more than 35 million copies!) Paine donated the proceeds to Washington’s army.

For the first time, mass public opinion had swung toward the cause of independence.

Adapted from Don’t Know Much About History which discusses the Revolution and Thomas Paine’s unhappy fate. In Paris during the French Revolution, Paine was imprisoned by revolutionary authorities. Upon his eventual release, he wrote an angry open letter to his old comrade George Washington, in which he skewered Washington for not having done enough to secure his release from the French prison. Paine later returned to America but when he died in 1809, no church in American would accept his body for burial as he was an atheist. The man who influenced history Paine was buried with a handful of people in attendance at his farm in New Rochelle, New York. His remains were then removed to his native England for reburial but were later lost.