“Why do Americans and Canadians Celebrate Labor Day?”

This Ted-Ed animated video explains the history of the holiday is a few years old. But it still matters today. (Reposted from 9/1/2014)

You can also view it on YouTube:

You can read more about the history and meaning of Labor Day in this piece I wrote for CNN a few years ago:

“The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”

Read more about the period of labor unrest in Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

(Originally posted on 1/24/2013; revised 8/11/2024)

Photo courtesy The Mount https://www.edithwharton.org/discover/edith-wharton/

You may have been assigned to read Ethan Frome in high school. Or you have read or seen the grand dramas of New York Society, The House of Mirth or The Age of Innocence. That’s how you know the name Edith Wharton.

Born in New York City, January 24, 1862: Edith Newbold Jones, who achieved fame as Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1921 (for The Age of Innocence).

But the other lesser-known aspect of Wharton’s life is her experience in France during World War I, where she founded hospitals and refugee centers for women and children.

Romance, scandal and ruin among New York socialites—long before this was the stuff of People, and “Gossip Girl,” it was the subject matter for Edith Wharton’s most famous works. In such novels as The House of Mirth (1905) and The Age of Innocence (1920), Wharton painted detailed, acid portraits of high society life. In doing so, she created heartbreaking conflicts beneath the façade of wealth and manners. Again and again, characters like Newland Archer and Lily Bart were forced to choose between conforming to social expectations and pursuing true love and happiness. Her most famous work set outside the realm of high-tone New York was Ethan Frome (1911), set in wintry, rural Massachusetts.

Edith Wharton in France during World War I (Photo: Courtesy The Mount Edith Wharton’s Home)

Wharton had spent years in Europe as a child and teenager. But she moved to France in 1910 while war in Europe was on the horizon and her marriage to socialite Teddy Wharton disintegrated.

Once the war broke out, she also wrote urging the United States to join the war. Then she saw the hardship caused as the fighting that tore across Europe starting in August 1914 created masses of refugees.

American novelist Edith Wharton set up workshops for women all over Paris, making clothes for hospitals as well as lingerie for a fashionable clientele. She raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for refugees and tuberculosis sufferers and ran a rescue committee for the children of Flanders, whose towns were bombarded by the Germans. Her friend and fellow author Henry James called her the “great generalissima”.

Source: Radio France International: “Edith Wharton-The American novelist who joined France’s WWI effort”

She started in her neighborhood with sewing workshops that eventually employed more than 800 women, opened hostels for tuberculosis patients and refugee children, hosted benefit concerts, sent dispatches from the war front.

In the first year of her work, her Children of Flanders Rescue Committee could record:

Refugees assisted: 9,229

Meals served: 235,000

Refugees for whom employment has been found: 3,400

Garments distributed: 48,333

For her wartime work, in 1916 Wharton was awarded France’s highest decoration – a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Edith Wharton died in Paris in 1937 and is buried in Versailles. Here is her New York Times obituary.

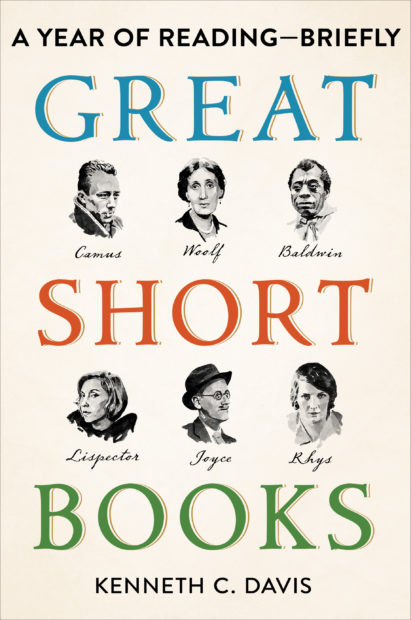

Edith Wharton is one of 58 writers featured in Great Short Books

The Mount is Wharton’s restored home in the Berkshires in Massachusetts.

[Originally posted August 10, 2015; updated 8/10/2023]

“We are challenged with a peace-time choice between the American system of rugged individualism and a European philosophy of diametrically opposed doctrines— doctrines of paternalism and state socialism. . . . Our American experiment in human welfare has yielded a degree of well- being unparalleled in all the world. It has come nearer to the abolition of poverty, to the abolition of fear of want than humanity has ever reached before.” –Herbert Hoover, “Campaign Speech” (October 22, 1928)

Herbert and Lou Henry Hoover in their Washington, DC home the morning after he was nominated to run for president (1928). (Courtesy: The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum)

Born on August 10, 1874, Herbert Clark Hoover, the 31st president of the United States. Herbert Hoover was born into a Quaker family in Iowa, and orphaned at nine. He went to live with relatives in Oregon. A college education at Stanford led to a career in the mining industry and a great personal fortune. You may know that he was the Republican president when the Stock Market crashed in 1929 and he attempted to lead the country through the first years of the Great Depression. Hoover was defeated by Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932.

But you may not know that Hoover was considered a hero and savior to millions of people. First during World War I, he had organized food relief programs in war-torn Belgium.

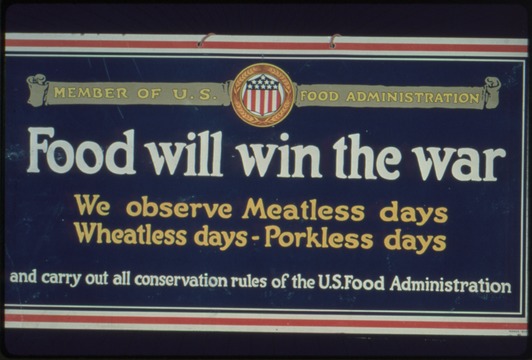

According to the Herbert Hoover Presidental Museum and Library, Hoover was named to head the U.S. Food Administration, which guided the effort to conserve resources and supplies and to feed America’s European allies.

National Archives https://catalog.archives.gov/id/512516

“Hoover became a household name—‘to Hooverize’ meant to economize on food. Americans began observing ‘Meatless Mondays’ and ‘Wheatless Wednesdays’ and planting War Gardens.”

Later, in the aftermath of World War I, Russia was in the throes of Europe’s greatest calamity since the days of the Black Plague. More than five million died in the new Soviet Russia when famine struck. In 1921, Herbert Hoover led America’s response to the “Great Famine,” subject of a PBS documentary and is credited with saving millions of lives.

Hoover gets hard knocks for the hard times of the Depression and his flawed response to the problems confronting America. But others assess him more generously. Historian Richard Norton Smith once noted:

“Herbert Hoover saved more lives through his various relief efforts than all the dictators of the 20th century together could snuff out. Seventy years before politicians discovered children, he founded the American Child Health Association. The problem is, Hoover defies easy labeling. How can you categorize a ‘rugged individualist’ who once said, ‘The trouble with capitalism is capitalists; they’re too damn greedy.’ ”

“Remembering Herbert Hoover,” New York Times, August 10, 1992

During the food scarcity in the height of the Covid pandemic, I wrote about Hoover’s wartime efforts in this post: “Where Is Herbert Hoover When We Need Him?”

Some Fast Facts about Herbert Hoover:

✱ Hoover was the first president born west of the Mississippi.

✱ His wife, Lou, was the only female geology major at Stanford when they met. They later collaborated on a translation from Latin of a mining and metallurgy text, De Re Metallica, published in 1912. While they lived in China, the Hoovers lived through the 1900 Boxer Rebellion and both learned Chinese, and they sometimes spoke to each other in Chinese at the White House.

✱ Hoover’s inaugural in 1929 was the first to be recorded on talking newsreel.

✱ Hoover was the first of two Quaker presidents. (The other was Richard M. Nixon.)

President Hoover died on October 20, 1964 in New York City. He was 90 years old. Hoover’s New York Times obituary. The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library & Museum offers archival materials and online exhibitions.

You can read more about Hoover in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Books/Random House Audio)

(Post updated 6/20/2023)

Now that Juneteenth has become a national holiday observed as the other “Independence Day,” it is time to look back to the first Independence Day — July 4th, 1776.

As we approach Independence Day, we should rightly celebrate the ideas articulated in the nation’s founding document:

…that all men are created equal…

… they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness

… Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed

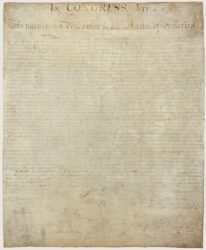

Source: National Archives Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

These were radical ideas that changed the nation and the world. But as the nation is going through an examination of the role slavery played in American History, it is important to recognize its role to the Founders at Philadelphia.

You cannot teach American History without acknowledging the role slavery played. And talking about the men who signed the Declaration is one way to do that.

Read: “The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles” (Social Education, March/April 2020)

This is the first in a series of posts about the men who signed the Declaration of Independence and what became of them. Most of these men remain somewhat obscure. They have also been mythologized in some online forums. Many of them played a significant role in the early republic before, during, and after July 4, 1776. The entire series is posted in this site’s Blog category.

Slavery existed in all thirteen of the future states and at least 40 of the 56 signers enslaved people or were involved in the slave trade. One focus of the series is to show which of these men enslaved people or otherwise participated in the slave trade. A “YES” after their listing means they enslaved people; a “NO” means they did not.

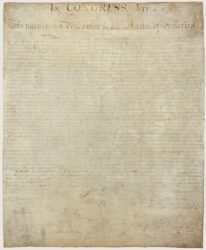

Declaration of Independence (Source: National Archives https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor.

Those strong words concluded the Declaration of Independence when it was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. Then what happened?

There is little question that men who eventually signed that document were putting their lives at risk. The identity and fates of a handful of those Signers is well-known. Two future presidents — Adams and Jefferson— and America’s most famous man, Benjamin Franklin, were on the Committee that drafted the document.

But the names and fortunes of many of the other signers, including the most visible, John Hancock, are more obscure. In the days leading up to Independence Day, I will offer a thumbnail sketch of each of the Signers in alphabetical order. Some prospered and thrived; some did not: How many of those Signers actually paid with their Lives, Fortunes, and Sacred Honor?

–John Adams (Massachusetts) Aged 40 when he signed, he went on to become the first vice president and second president of the United States.

Adams was very smart. But he misjudged the nation’s birthday. After Congress voted on a resolution in favor independence on July 2, he was convinced that would be a day of celebration:

“The Second Day of July 1776 will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. . . . It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires, and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

–John Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776 (National Archives)

By 1790, Adams was convinced that his place in the history to be written would be diminished.

“The history of our Revolution will be one continued lie from one end to the other,” he wrote fellow Founder Benjamin Rush in 1790.

“The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his rod –and thenceforward these two conducted all the policies,

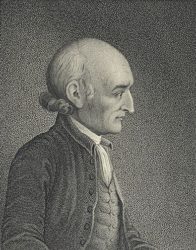

Portrait of John Adams at age 88 by Jane Stuart, after Gilbert Stuart, 1824. (National Park Service)

negotiations, legislatures, and war.”

Adams died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration in 1826 at age 90. (Jefferson died that same day) NO

The Adams house is a National Historical Park.

–Samuel Adams (Mass.) Older cousin to John, Samuel Adams was 53 at the signing. He went on to a career in state politics, initially refused to sign the Constitution because it lacked a Bill of Rights, and was governor of Massachusetts. He died in 1803 at 81. NO

–Josiah Bartlett (New Hampshire) Inspiring the name of the fictional president of West Wing fame on TV, Bartlett was a physician, aged 46 at the time of the signing. He helped ratify the Constitution in his home state, giving the document the necessary nine states to become the law of the land. Elected senator he chose to remain in New Hampshire as governor. Three of his sons and other descendants also became physicians. He died in 1795 at age 65. YES

–Carter Braxton (Virginia) A 39-year-old plantation owner, Braxton was looking to invest in the slave trade before the Revolution. Initially reluctant about independence, he helped fund the rebellion and lost a considerable fortune during the war — not because he was a signer, but because of shipping losses suffered during the war itself. He later served in the Virginia legislature and died in 1797 at age 61, far less wealthy than he had been, but also far from impoverished. YES

–Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Maryland) A plantation owner, 38 years old and one of America’s wealthiest men at the signing, Carroll was the only Roman Catholic signer and the last signer to die. With hundreds of enslaved people on his properties, Carroll considered freeing some of them before his death and later introduced a bill for gradual abolition in Maryland, which had no chance of passage. At age ninety-one, he laid the cornerstone of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as a member of its board of directors. He died in 1832 at age 95. YES

Update: Carroll’s cousin was John Carroll, a Jesuit priest, first Roman Catholic bishop in the United States, and a founder of Georgetown College. The New York Times has reported how, in 1838, Georgetown sold 272 enslaved people to keep the college financially afloat.

[Post revised 6/30/2023]

Key to Numbers in “The Declaration Mural” by Barry Faulkner

The final entry in a blog series profiling the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence. The series begins here. The previous posts can be found in this website’s Blog category.

AS THE NATION examines the role slavery played in its history, it is important to recognize that slavery was an issue in 1776. Among the men who eventually signed the Declaration, at least forty of them enslaved people or took part in the slave trade.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

A New Hampshire slaver. A forgotten founder who died in debt and disgrace. A college president. A legendary bullet maker. Jefferson’s teacher –and a murder victim. Last but not least among the 56 signers. A “YES” following the entry means the Signer enslaved people; “NO” means he did not.

•William Whipple (New Hampshire) Often described as a 46-year-old “merchant,” he was more precisely a sea captain who made a fortune sailing between Africa and the West Indies — in other words, the merchandise was human cargo.

He also enslaved people and one of those men, known as Prince, accompanied Whipple throughout his illustrious career as an officer in the Revolution. It was thought that Prince was the Black man depicted in the famous “Washington Crossing the Delaware” painting. But that is not accurate because Prince and Whipple were far from the action that night. Whipple later served in a variety of state offices in New Hampshire and legally manumitted Prince –who also went by the name of Caleb Quotum — in 1784. Whipple died in Portsmouth in 1785. YES

Gravestone of Prince Whipple https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/whipple-prince-1750-1796/

•William Williams (Connecticut) A 45-year-old merchant, he was a veteran of the French and Indian War who was under command of his uncle Ephraim Williams, who was shot and killed in the war. (Ephraim Williams’s will provided funds for the founding of what became Williams College in Massachusetts.) Planning to follow his father as a minister, he attended Harvard but instead opened a store and became a successful merchant.

Williams married Mary Trumbull, the daughter of Connecticut’s Royal Governor. Governor Trumbull was a Royal Governor who supported the patriot cause and was a friend and adviser of George Washington. One of Mary Trumbull’s brothers, John Trumbull, became the most famous painter of the American Revolution, and another later became Connecticut’s Governor.

William Williams was not present for the July vote but signed the Declaration and was a tireless supporter of the war effort. After a long career in public service, he died in 1811, aged 81. NO

•James Wilson (Pennsylvania) Scottish-born, he was a 33-year-old lawyer at the time of the signing and one of the most important Founding Fathers you probably never heard of. A key supporter of the Declaration, Wilson was among the signers and Philadelphia elites who were attacked in his home during the war in a riot over food prices and scarcity.

Wilson was also a key member of the Constitutional Convention, credited with several significant compromises. Although hopeful to be made Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court, he was appointed an associate by Washington. But land speculation ruined him and he ended up in debtor’s prison, like his colleague Robert Morris (See series post #7) before his death in disgrace at age 55 in 1798, an embarrassment to his Federalist friends and colleagues. NO

https://dontknowmuch.com/wp-admin/post.php?post=8045&action=edit The official portrait of Supreme Court Justice James Wilson.

•John Witherspoon (New Jersey) Another profoundly influential immigrant, the Scottish-born minister was the 53-year-old president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) where his hatred of the British influenced many students including notable schoolmates Aaron Burr and James Madison. He lost a son at the battle of Germantown in 1777, but continued his career in Congress. After the war, he attempted to rebuild the college and was a prime mover in the growth and organization of the Presbyterian Church. He died in 1794 in Princeton, where he is buried, at age 71. YES

A photograph of Maclean House, also called the President’s House, at Princeton University. Built 1756. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Maclean_house.jpg

•Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut) A 49-year-old lawyer, he was also a veteran of the French and Indian War who was not present for the vote and signed at a later date. Wolcott was in New York when Washington’s troops tore down a statue of King George III after hearing the Declaration of Independence read. He is credited with the plan to melt down the lead statue and turn it into bullets for the war effort. He served in the Connecticut militia during the Revolution and held a series of state posts after the war including as governor of Connecticut at his death in 1797, aged 71. YES

•George Wythe (Virginia) A 50-year-old lawyer at the signing, he may have made his greatest mark as a teacher of law to Thomas Jefferson who lived with Wythe while at the College of William and Mary –as well as later students including James Monroe, future Chief Justice John Marshall, and congressman Henry Clay, earning him the title “America’s first law professor.”

He died in 1806 , around 80, apparently murdered by a nephew by arsenic poisoning. The nephew was perturbed that Wythe had emancipated his enslaved people and planned to give half his estate to one of those emancipated people. The nephew was acquitted of murder after the testimony of a formerly enslaved woman was disallowed because she was black. The nephew was convicted of forging his uncle’s checks. YES

George Wythe, Signer of Declaration of Independence New York Public Library Digital Gallery (Digital Image ID: 484381)

Read the story of James Wilson and the Philadelphia Riot in America’s Hidden History.

Read more about slavery in the founding in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

[Post revised 6/29/2023]

This is Part 10 of a blog series profiling the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence. The series begins here. The previous posts can be found in the website Blog category.

As we approach Independence Day, we should rightly celebrate the ideas articulated in the nation’s founding document:

…that all men are created equal…

… they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness

… Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed

Source: National Archives Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

The men who ultimately signed this document were taking an enormous risk:

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Declaration of Independence (Source: National Archives https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration

But we must also acknowledge another fact: You cannot teach American History without acknowledging the role slavery played. And talking about the men who signed the Declaration is one way to do that.

A victim of the British. Two Irish immigrants, one an indentured servant. A reluctant lawyer. An orphaned carpenter. (A Yes after their name means they enslaved people; a No means they did not.)

•Richard Stockton (New Jersey) Of the signers who paid for their actions, this successful and much-admired 45-year-old attorney at the signing, may have suffered most. Betrayed by Tory Loyalists in his home state, he was captured by the British in 1776, although later released in a prisoner exchange, not for having sworn allegiance to the King, as reported in a much-disputed rumor of the day. His New Jersey home was occupied and damaged by the British but later restored. Stockton was in poor health after the experience in captivity but lived until 1781, when he died of throat cancer.

Stockton is also credited with recruiting John Witherspoon, an influential Sottish minister, (See next installment in series) to become president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton). His daughter, Julia, was married to Benjamin Rush, another signer.

“Stockton’s home ‘Morven’ had been occupied by British General Cornwallis. Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote: ‘The whole of Mr. Stockton’s furniture, apparel, and even valuable writings have been burnt. All his cattle, horses, hogs, sheep, grain and forage have been carried away by them. His losses cannot amount to less than five thousand pounds.’” (Source: The Society of the Descendants of the Signers.)

His home Morven, later served as the New Jersey Governor’s Mansion from 1954-1981. Today, his name is familiar to most people because there is rest stop on the New Jersey Turnpike named in his honor. YES

•Thomas Stone (Maryland) Among the conservatives in Congress, he was a 33-year-old attorney at the signing, reluctant about independence, but then joining in the favorable vote. He wrote:

“I wish to conduct affairs so that a just and honorable reconciliation should take place, or that we should be pretty unanimous in a resolution to fight it out for independence. The proper way to effect this is not to move too quick. But then we must take care to do everything which is necessary for our security and defense, not suffer ourselves to be lulled or wheedled by any deceptions, declarations or givings out. You know my heart wishes for peace upon terms of security and justice to America. But war, anything, is preferable to a surrender of our rights.” (Source: The Society of the Descendants of the Signers)

Thomas Stone’s home is a National Historic site. Habre de VentureFront View, September 2009 (Photo via wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Habre_de_Venture_Front_Sept_09.JPG

Another son of a wealthy planter, he had a low profile after the signing, helping write the Articles of Confederation but not signing them. He also declined to take part in the Constitutional Convention, when his wife, who fell ill following an earlier inoculation against smallpox, died in 1787. Apparently despondent, he died four months later in 1787 at age 44. YES

•George Taylor (Pennsylvania) Arriving in America as an indentured servant from Ireland, he was a 60-year-old merchant and iron maker at the signing. He had risen at the foundry where he worked to become bookkeeper, later purchased the business after his employer’s death, and then married the late owner’s widow.

Taylor was not in the influential Pennsylvania delegation for the July vote, but joined Congress when Loyalists in the Pennsylvania delegation were fored to resign. He signed the document in August. During the war, his foundry provided cannon and cannonballs for the war effort, but Congress was notoriously slow to pay its bills and his business suffered. He died in 1781 at age 65. YES

•Matthew Thornton (New Hampshire) An Irish-born physician, he was around 62 at the signing, a veteran surgeon who had served with the New Hampshire militia in the French and Indian War. A latecomer to Congress, he joined in November 1776 and was later permitted to add his name to the document. He later served as a state judge and then operated a farm and ferry before his death in 1803 at about age 89. NO

•George Walton (Georgia) Orphaned and apprenticed as a carpenter, he was a 35-year-old, self taught attorney at the signing. Although his exact birth date is unknown, some claim that he was the youngest Signer – a distinction usually given to Edward Rutledge (See previous entry).

Serving with the Georgia militia, he was shot and captured by the British in 1778. He was held for a year before being exchanged for a British officer –even though it was known he was a Signer. He later served in a variety of state offices, including governor and senator from Georgia, and built a home on lands confiscated after the war from a Tory, or Loyalist. He is implicated in the events that led to the duel that killed fellow signer and political rival Button Gwinnet (see Part 3 of series). He died in February 1804, presumably aged 63. NO

Update 6/29/2021:

“Unlike most men of property and influence in Georgia, Walton did not own slaves. There is little record of his public views on slavery, but it is known that shortly after leaving the governor’s mansion, Walton spoke out against what he called ‘barbarian’ treatment of members of an African-American Baptist congregation in Yamacraw, Georgia, in 1790.”

Read more about slavery in the founding in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY

[Post updated 6/28/2023]

This is Part 9 of a blog series profiling the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence. The series begins here. The complete series can be found in the website Blog category.

As we approach Independence Day, we should rightly celebrate the ideas articulated in the nation’s founding document:

…that all men are created equal…

… they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness

… Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed

Source: National Archives Declaration of Independence: A Transcription

The men who ultimately signed this document were taking an enormous risk:

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Declaration of Independence (Source: National Archives https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration

But we must also acknowledge another fact: You cannot teach American History without acknowledging the role slavery played. And talking about the men who signed the Declaration is one way to do that.

Betsy Ross’s uncle. The “first psychiatrist.” The youngest signer. The Great Compromiser. An Irishman named Smith. The next five signers. (A Yes after their name means they enslaved people; a No means they did not.)

•George Ross (Pennsylvania) The son of a Scottish-born minister, he was a 46-year-old attorney at the signing, a Loyalist or Tory, before turning to the Patriot cause in 1775. He served as a Colonel in the Pennsylvania militia. Yes, he was Betsy’s uncle by marriage, but the rest of the Ross flag story has been dismissed as family legend.

Ross left Congress in early 1777 due to illness — severe gout, a form of arthritis once described as the “rich man’s disease” that afflicted a number of other signers. He later served as a Pennsylvania judge before his death in 1779 at 49, following a severe attack of gout. NO

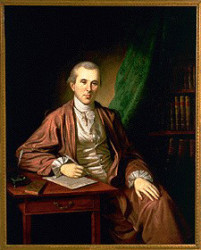

Dr Benjamin Rush by Charles Willson Peale c. 1783. Winterthur Museum

•Benjamin Rush (Pennsylvania) Raised by a widowed mother, he was a 30-year-old physician at the signing, youngest in the influential Pennsylvania delegation. He was elected after the July vote and his diaries, letters, and notes provided some of the best portraits of many of the signers and other founders.

He served as surgeon general of the armies during the war, and became an early abolitionist while still a slaveholder himself. Rush was also an early advocate of many modern medical practices, while at the same time practicing bloodletting. He established the first free medical clinic and remained in Philadelphia during a yellow fever epidemic in 1793 when the city was the nation’s capital, spoke against capital punishment, and in favor of the idea that there was mental illness which led to his being called “The Father of American Psychiatry.” He died of typhus in 1813 at age 67. YES

Rush is honored at Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum with a Medicinal Plant Garden bearing his name.

•Edward Rutledge (South Carolina) Son of an Irish immigrant physician, he was a 26-year-old attorney at the signing, the youngest of the signers. A wealthy planter as well as a much-admired attorney, Rutledge initially opposed the Declaration before changing his mind to support the favorable vote.

He later left Congress and was captured by the British while serving in the militia when Charleston fell in May 1780. He was held in St. Augustine for nearly a year. After the war, his finances and businesses flourished and he returned to state politics. Offered a Supreme Court seat by George Washington, he was instead elected governor of South Carolina in 1789, but died at age 50 in 1800, before his term ended. YES

•Roger Sherman (Connecticut) A self-educated son of a farmer, he was a prosperous merchant, attorney, and politician, aged 55 at the signing. He would sign four of the central documents in America’s foundation: the Continental Association, the Declaration (he was a member of the draft committee), the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution

This painting by John Trumbull depicts the moment on June 28, 1776, when the first draft of the Declaration of Independence was presented to the Second Continental Congress. (Source: Architect of the Capitol) https://www.aoc.gov/explore-capitol-campus/art/declaration-independence

It was at the 1787 Constitutional convention that Sherman proposed the “Great Compromise” that ended the deadlock between large and small states. He was also a true “Founding Father”– after Carroll (18 children) and Ellery (16 children), Sherman fathered the third most children among the signers -15. A leading Federalist, he served in the House and Senate, where he was serving at his death in 1793 at age 72. NO

•James Smith (Pennsylvania) Another immigrant signer, he was born in Northern Ireland and was around 57-years-old at the signing, another self-taught attorney. He had been an outspoken advocate of challenging oppressive British laws and called for the boycott of British goods that was later adopted by the First Continental Congress.

He also joined the Pennsylvania militia and was elected an officer. After the July vote, he signed the Declaration and then rode to York, Pennsylvania to have it read aloud on July 6. He served as Brigadier General of the Pennsylvania militia and later returned to law practice and state offices before his death in 1806 at about age 87. NO

Read: “The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles” (Social Education, March/April 2020)

And read about slavery in the founding in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY

[Updated 6/27/2023]

This is Part 8 of a blog series profiling the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence. The series begins here. The complete series can be found in this website’s Blog category.

In adopting and then signing the Declaration, these men were taking a significant risk. The closing words of the Declaration were not to be taken lightly.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Declaration of Independence (Source: National Archives https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration

But it is also true that at least 40 of these 56 men who pledged themselves to the idea that “All Men are created” and are entitled to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” enslaved people. A “YES” following an entry means the Signer enslaved people; “NO” means he did not.

Minister turned whaleboat captain and lawyer. Self-taught planters’ sons. A Nay vote. A rare bachelor. And a veiled man. The next six signers:

•Thomas Nelson, Jr. (Virginia) Another son of a wealthy planter, he was a 37-year-old merchant-planter at the signing who enslaved more than 400 people. He raised money to supply troops and even commanded militia. Legend has it that he fired a cannon at his own Yorktown mansion during the 1781 siege when told that it was British headquarters. The war cost him financially and he was in ill health, retiring as Virginia’s governor and living on his plantation until his death at 50 in 1789. YES

•William Paca (Maryland) An attorney and wealthy planter’s son, he was 35 at the signing. A patriot leader in somewhat conservative Maryland, Paca (pronounced Pay-cah) helped bring the state to favor independence at Philadelphia. He raised funds for the war effort and later, as Congressman, worked to support veterans.

During the Constitutional debate, Paca was a firm believer in states rights and individual rights, and led the Antifederalist movement in Maryland.

William Paca by Charles Willson Peale MSA SC 4680-10-0083 Source Maryland State House

“Even though he had many reservations, he voted in 1788 to approve the Constitution. He advocated 28 amendments to the Constitution, including those on freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and protection against judicial tyranny, and many of his proposed amendments became a part of the Bill of Rights.”

[Source: The Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration.]

He was twice married, but both wives died after childbirth, and Paca also fathered two children out of wedlock, one to a mixed race woman while serving in Philadelphia, according to the Society of the Descendants. He was later appointed a federal judge by President Washington, and was in that post at his death in 1799 at age 58. YES

Robert Treat Paine (Courtesy: Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts)

•Robert Treat Paine (Massachusetts) Overshadowed by two Adamses and Hancock, he was a minister turned attorney, 45-years-old at the signing, who had also been a sea captain on a whaler.

“In 1754, as Captain of the Seaflower, he led a whaling expedition from Cape Cod to Greenland and left behind what is believed to be the earliest illustrated log of a whaling venture kept by an American.” [Source: Society of the Descendants of the Signers]

He is perhaps best known as one of the prosecutors in the 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged in “Boston Massacre.” His friend and fellow delegate John Adams had served successfully as their defender. In 1780, he was among the founders of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the first American groups dedicated to expanding scientific knowledge and learning. After the war, he remained active in Massachusetts politics, becoming the state’s Attorney General, and was named a state judge by John Hancock until his retirement in 1804 due to deafness. He died in 1814 at age 83. NO

•John Penn (North Carolina) A wealthy planter’s son who taught himself to read and write, he was a 36-year-old attorney at the signing. He remained in Congress and was one of the signers who also signed the first American constitution, the Articles of Confederation. He retired to private law practice and died in 1788 at age 48. YES

•George Read ( Delaware) Among the conservative delegates, he was a 42-year-old lawyer at the time of the signing but had voted against independence on July 2. He served in state offices until ill health forced his resignation. But he returned to Philadelphia to take part in the Constitutional convention and was leading voice for small states’ rights and led the ratification forces in Delaware, the first state to ratify the Constitution. Elected to the Senate, he resigned to take a judgeship in Delaware before his death in 1798 at age 65. YES

•Caesar Rodney (Delaware) Another self educated attorney, son of a planter, he was 47 at the signing. He is perhaps best known for an 80-mile ride in a storm to break a deadlock that put Delaware in the Independence column –which cost him favor with conservatives in his home state. He later wrote in a letter:

“I arrived in Congress (tho detained by thunder and rain) time enough to give my voice in the matter of independence . . . We have now got through the whole of the declaration and ordered it to be printed so that you will soon have the pleasure of seeing it.” [Source: The Society of the Descendants]

Statue of Caesar Rodney on his ride-Rodney Square Wilmington, DE (Public Domain)

Rodney also exemplifies the Great Contradiction of the Declaration, as he had earlier introduced legislation against the foreign slave trade:

“In 1766, as the Speaker of the [Delaware] Assembly, he introduced a bill to prohibit the importation of slaves into Delaware. At this time he was living in Byfield, a plantation of 1,000 acres, and owned 200 slaves. It is clear that he was pondering questions of the Colony’s and Mankind’s liberty and freedom. Indeed, at his death fourteen years later, he directed that all his slaves should be freed then, or shortly thereafter.” [Source: The Society of the Descendants]

One of the three bachelor signers (Francis Lee and Thomas Lynch were the others), Rodney remained in the Congress until he became Delaware’s state president. A cancerous growth on his face was untreated and he covered it with a silk veil, worn for a decade before his death in 1784 at age 55. YES

Read more about the place of slavery in the Founding of the United States in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

[Updated 6/26/2023]

As the role of slavery in the nation’s founding is debated and the teaching of a full and accurate American history is questioned, it must be made clear that slavery was central to the nation’s beginnings and institutions. One way to examine that is by looking at the men who signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1776.

Among the men who signed the Declaration, at least forty of them enslaved people or took part in the slave trade. This is Part 7 in a series that begins here. It tells the stories of what happened to the men who pledged “our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor.” Read the other entries here in my blog category.

Declaration of Independence (Source: National Archives https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration

A tavern owner’s son. Two of America’s wealthiest men –both named Morris. And the first to die. The next five signers in this series. “YES” following the entry means the Signer enslaved people; “No” means he did not.

•Thomas McKean (Delaware) Son of a Pennsylvania farmer-tavern owner, McKean was a self educated, 42-year-old attorney turned politician at the time of the signing (although he did not sign in 1776).

in 1768 he was elected to the American Philosophical Society, a distinguished intellectual society founded by Benjamin Franklin. In 1769 McKean became a trustee of the Academy of Newark, the successor to Allison’s school at New London. He received honorary degrees from Princeton in 1781, Dartmouth in 1782 and Pennsylvania in 1785. Source: The Society of Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration.

A vigorous patriot, he held offices in both his native Pennsylvania and Delaware and was a key supporter of the Declaration. When another delegate from Delaware was absent and the state might vote against independence, McKean sent a horse and rider to collect fellow delegate Caesar Rodney and bring him back to vote — an 80-mile ride in a storm.

According to the National Constitution Center, as Pennsylvania judge:

McKean was a prominent early supporter of a strong judiciary, one strong enough to overturn a state law, if needed, as unconstitutional. He served for 22 years as Chief Justice for one of the most-influential state courts in the new republic.

He voted to approve the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, but he left Philadelphia before the document was signed, to rejoin the fight against the British.

Historians believe he was the last person to sign the document, either in early 1777 or as late as 1781.

McKean represented Delaware in the first two Continental Congresses, fought alongside George Washington and he briefly served as President of the Continental Congress in 1781, as British forces surrendered at Yorktown. McKean and his family were pursued by the British but never captured. A vocal advocate of the Constitution, he served in many state posts, including governor of Pennsylvania, and prospered after the war. He died in 1817 at age 83. YES

•Arthur Middleton (South Carolina) A 34-year-old plantation owner at the signing, he replaced his father –thought too conservative — in Congress. Educated in England, he became active in patriot politics. One of the few delegates to serve in the wartime militia, he was captured in Charleston in 1780, along with Thomas Heyward (Post #4) and Rutledge, two other South Carolina signers. Although his home had been destroyed he was released by the British and returned to Congress in 1781. After the war he returned to his plantation where he died at age 44 in 1787. YES

•Lewis Morris (New York) Another of the wealthy members of prominent New York families in the state’s delegation, Morris was a 50-year-old land owner with large holdings in what is now the Bronx in New York City. Although his home was assaulted by British troops during the war, it was attacked and severely damaged because of its value, not because he was a signer. Morris led troops of the militia during the vote in July, but then led the New York delegation in later signing the Declaration, making it unanimous. Morris rebuilt the family home and land holdings after the war and was a leader with Alexander Hamilton in ratification of the Constitution. He died in 1798, aged 71 and his former plantation is known today as the Morrisania section of the Bronx. YES

•Robert Morris (Pennsylvania) (No relation to Lewis Morris above.) One of the wealthiest individuals in America, he was a 42-year-old Philadelphia merchant and speculator when he signed. Born in Liverpool, he had come to America and made a fortune as a merchant, becoming the “Financier of the Revolution.” Accused of profiteering during the war, he was attacked in the Philadelphia home of fellow signer James Wilson. A delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he declined to serve as Washington’s secretary of Treasury, recommending Alexander Hamilton instead. He later became a Senator. But he lost his fortune through land speculation and was bankrupted and put in debtor’s prison. He died in poverty and relative obscurity in 1806, aged 72. YES

•John Morton (Pennsylvania) A farm boy turned surveyor, he was 52-years-old at the time of the signing. He has two key distinctions: his vote pushed Pennsylvania into the pro-independence camp and he was first signer to die.A member of the committee writing the Articles of Confederation, he fell ill with tuberculosis in 1777 and died before they were ratified, at about age 52. He left his farm and enslaved people to his wife and children who had to flee from a British attack. YES

Read more about the place of slavery in the Founding of the United States in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

[Post updated 6/25/2023]

This is the sixth in a series of posts about the men who signed the Declaration of Independence and what became of them. The series begins here. Or follow the series here.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

As the nation goes through an examination of the role slavery played in American History, it is important to recognize its place in Philadelphia in 1776. You cannot teach American History without acknowledging that slavery was central to the founding of the country. And talking about the men who signed the Declaration is one way to do that. The Yes after a name means the Signer enslaved people; No means he did not.

In this group: More wealthy planters and a couple of very wealthy New York merchants.

•Richard Henry Lee (Virginia) A 41-year-old planter from a prominent Virginia family –his younger brother Francis Lightfoot (See previous post) was also there– Lee deserves more acclaim than he usually gets. A “great orator,” said John Adams, Lee introduced the resolution for independence. He left Congress to attend to state business in Virginia and didn’t vote for the resolution or the Declaration, which he signed later in the summer of 1776.

Richard Henry Lee National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Duncan Lee and his son, Gavin Dunbar Lee

He was one of the few signers to actually serve with a Virginia militia unit. He remained in politics after the war, becoming a vocal opponent of the Constitution but an advocate for the Bill of Rights. He was elected to the U.S. Senate but resigned in ill health and died at age 62 in 1794. YES

•Francis Lewis (New York) A native of Wales, he was a 63-year-old merchant at the time of the signing, a key supporter of George Washington, but was instructed not to vote for the Declaration by New York. He then signed in August. During the war, his wife was imprisoned by the British and died shortly after her release, leaving Lewis grief-stricken. He died in 1802 at age 89, was buried in an unmarked grave at Manhattan’s Trinity Church, and now, curious New Yorkers will know why there is a Francis Lewis Boulevard in Queens. YES

•Philip Livingston (New York) The 60-year-old member of one of New York’s wealthiest families, with an estate of 160,000 acres on the Hudson River, he was a merchant who favored the patriot cause. But like many New Yorkers, he was more moderate and cautious about declaring independence and was absent when the entire New York delegation abstained from the vote. He signed in August. (Robert Livingston, a cousin and member of the Declaration draft committee, was also absent from the vote and never signed the Declaration).

Philip Livingston (New York Public Library) https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-24a4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

“General Washington and his officers met at Philip’s residence in Brooklyn Heights after their defeat in the battle of Long Island, and decided to evacuate the island. The British subsequently used Philip’s Duke Street home as a barracks, and his Brooklyn Heights residence as a Royal Navy hospital. As the British occupied New York City, Philip and his family fled to Kingston, NY where he maintained another residence. Later, the British burned the city of Kingston to the ground as they did Robert R. Livingston’s mansion, Clermont, across the Hudson River.” (Source: Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Although he sold some of his property to support the war effort, his family continued to amass large land holdings in upstate New York. In poor health, he died at age 62 in 1778, when Congress was forced to evacuate Philadelphia and move to York, Pa. YES

•Thomas Lynch, Jr. (South Carolina) At 27, the second youngest signer (after Edward Rutledge also of South Carolina), he was born on one of the South’s major rice plantations. A lawyer, he was the son of a a wealthy rice planter, who suffered a stroke while a delegate in Philadephia. The younger Lynch was sent to Congress. (His father was unable to vote or sign.) Both left for home in poor health and the elder Lynch died en route.

During the debates after the adoption, Lynch was reported by John Adams to threaten secession:

If it is debated, whether their Slaves are their Property, there is an End of the Confederation. Our Slaves being our Property, why should they be taxed more than the Land, Sheep, Cattle, Horses, &c.

Source: John Adams diary 27, May – 10 September 1776 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society.

Hopsewee Plantation (Photo credit Alan Sherlock via Historic Hopsewee)

Lynch Jr. and his wife later sailed for the West Indies in the hope of regaining his health but both died at sea in 1779 when their ship was lost in a storm. Among the youngest signers, he was the youngest signer to die at age 30. YES

Read more about slavery and the Founders in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.