[Post revised January 20, 2026]

As we approach February –Black History Month– and the celebration of George Washington’s Birthday (AKA “Presidents Day”) on Monday February 16, it is an appropriate time to reflect on the connection of Presidents and Black History. That is especially true in this year that marks 250 years since America declared its independence with Jefferson’s timeless words –“All men are created equal.” This is what I have called “The American Contradiction”–that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles. (READ “THE AMERICAN CONTRADICTION”

Recognizing that fundamental truth is all the more important in the current political landscape, when teaching an accurate version of American History is under assault.

As the New York Times reported last year,

“Recent polls show that a majority of Americans of all political stripes are open to complex history that shows the bad along with the good. But Mr. Trump’s recent actions, some observers say, are part of an escalating attempt to use history as a wedge that separates ‘real’ Americans from naysayers who threaten the body politic.” New York Times, April 19, 2025, “Trump’s American History Revolution”

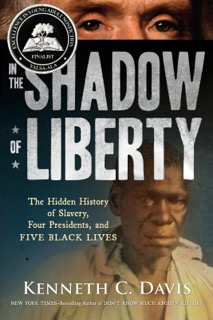

Having spent much of my career trying to correct the false narrative so many Americans were once taught, I believe the nation must honestly confront the role that enslavement played in the nation’s founding and development. In the Shadow of Liberty tells that story.

Did you know that many of America’s Founding Fathers—who fought for liberty and justice for all—were slave owners?

Through the powerful stories of five enslaved people who were “owned” by four of our greatest presidents, this book helps set the record straight about the role slavery played in the founding of America. These dramatic narratives explore our country’s great tragedy—that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

NOW AVAILABLE IN PAPERBACK

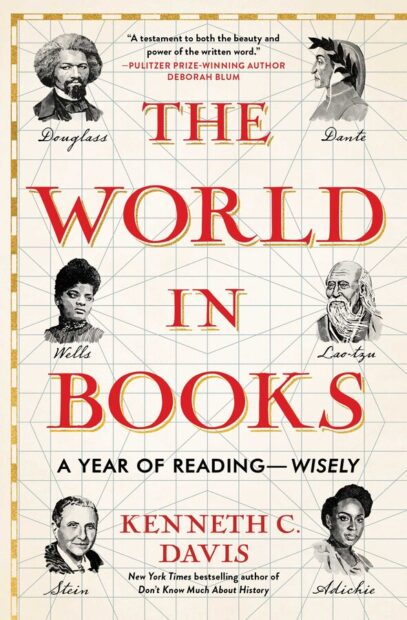

THE WORLD IN BOOKS: A YEAR OF READING–WISELY

Named to “The Most Anticipated: The Great Fall 2024 Preview” by The Millions

“Kenneth C. Davis’s The World in Books is a testament to both the beauty and power of the written word. And also, a very smart guide to books that have changed the way we think – and sometimes even changed us.”

–Deborah Blum, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of The Poison Squad and the bestseller, The Poisoner’s Handbook.

First Trade review from Kirkus Reviews

“A wealth of succinct, entertaining advice.” Full review

Now out from Scribner Books and Simon & Schuster Audio and available in paperback on October 21, 2025

Read more and order copies here.

More Praise for The World in Books:

“In his accessible, well-written, and unanticipatedly humorous The World in Books, Kenneth C. Davis takes readers on a journey that highlights fifty-two short yet provocative works of non-fiction. Highlighting both traditional favorites and contemporary classics, Davis offers his sharp insights in ways that appeal to the inquisitive mind, regardless of its familiarity with the selected texts. His poignant “Introduction” sets the stage for the contemporary relevance of why books like these matter in contemporary times, which makes this collection all the more relevant. Highly recommended for every person who treasures the freedom to read and values the transformative power it has for us all.”

—Dr. J. Michael Butler, Kenan Distinguished Professor of History, Flagler College and author of Beyond Integration

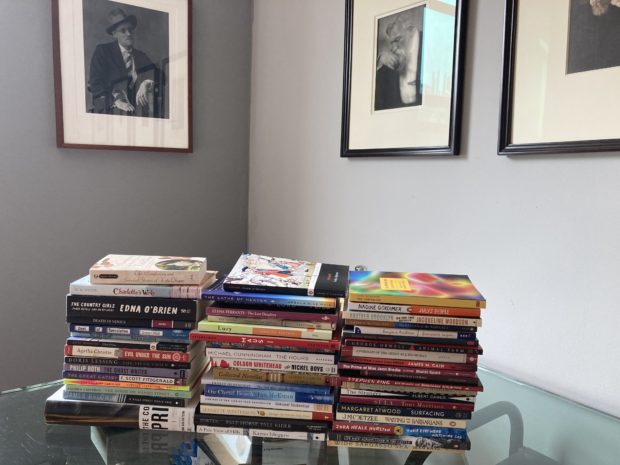

What a “Year of Reading–Wisely” looks like….

Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis

Among the 52 titles I have included are The Epic of Gilgamesh, Genesis, the poetry of Sappho, Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, and such profoundly influential writers as Frederick Douglass, Henry David Thoreau, Virginia Woolf, Helen Keller, James Baldwin, Susan Sontag, and Timothy Snyder.

The essential message of this book is that books matter–now more than ever. We must continue to educate ourselves. I believe that Open Books Open Minds.

I look forward to sharing my fundamental belief that books can change us and the world.

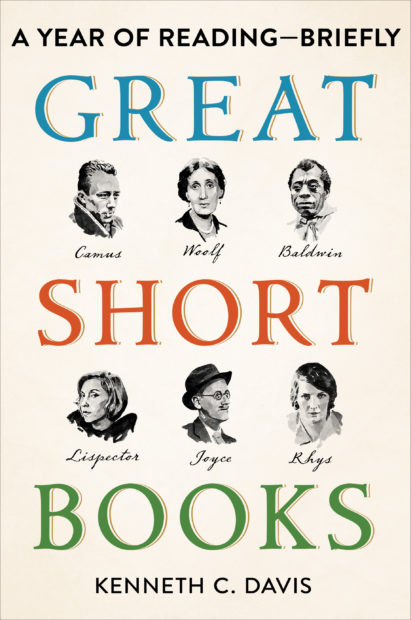

And please read and enjoy my guide to 58 excellent short works of fiction: Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly

NOW IN PAPERBACK

GREAT SHORT BOOKS:

A YEAR OF READING — BRIEFLY

Scribner/Simon & Schuster and Simon Audio (Unabridged audio download)

“An exciting guide to all that the world of fiction has to offer in 58 short novels — from ‘The Great Gatsby’ and ‘Lord of the Flies’ to the contemporary fiction of Colson Whitehead and Leïla Slimani — that, ‘like a first date,’ offer pleasure and excitement without commitment.” New York Times Book Review

Booklist “Editors’ Choice Adult Books 2022″

“…The most exceptional of the best books of 2022 reviewed in Booklist…”

“Delightfully accessible, Great Short Books: A Year of Reading–Briefly presents 58 fact-filled reviews of short books, a smorgasbord of titles sure to entice readers.” –Cheryl McKeon, Shelf Awareness

“I consider Davis’ ‘Great Short Books’ a gift to readers, a true treasure trove of literary recommendations.” —Sue Gilmore, SFGate

“Anyone who’s eternally time-strapped will treasure Kenneth C. Davis’ Great Short Books. This nifty volume highlights 58 works of fiction chosen by Davis for their size (small) and impact (enormous). Each brisk read weighs in at around 200 pages but has the oomph of an epic.” —Bookpage Full Review

“An entertaining journey with a fun, knowledgeable guide…. “ Kirkus Reviews

“A must-purchase for public and school libraries.” ALA Booklist

FIRST TRADE REVIEWS FROM KIRKUS, PUBLISHERS WEEKLY, BOOKLIST

“Davis feels that novels of 200 pages or less often don’t get the recognition they deserve, and this delightful book is the remedy…A must-purchase for public and school libraries.” *Starred Booklist review

“An entertaining journey with a fun, knowledgeable guide…. His love of books and reading shines through. From 1759 (Candide) to 2019 (The Nickel Boys), he’s got you covered.” –Kirkus Reviews

Full KIRKUS review here“Davis’s conversational tone makes him a great guide to these literary aperitifs. This is sure to leave book lovers with something new to add to their lists.” FULL PUBLISHERS WEEKLY REVIEW here

During the lock-down, I swapped doom-scrolling for the insight and inspiration that come from reading great fiction. Inspired by Boccaccio’s “The Decameron” and its brief tales told during a pandemic, I read 58 great short novels –not as an escape but an antidote.

“A short novel is like a great first date. It can be extremely pleasant, even exciting, and memorable. Ideally, you leave wanting more. It can lead to greater possibilities. But there is no long-term commitment.”

–From “Notes of a Common Reader,” the Introduction to Great Short Books

Read “The Antidote to Everything,” an excerpt from the Introduction published on Lit Hub

The result is a compendium that goes from “Candide” to Colson Whitehead, and Edith Wharton to Leïla Slimani. And yes, Maus and many other Banned Books and Writers.

What “A Year of Reading–Briefly” looks like

Voltaire in Great Short Books

Art © Sam Kerr

Edith Wharton in Great Short Books

Art © Sam Kerr

Advance Praise for Great Short Books: A Year of Reading—Briefly

“GREAT SHORT BOOKS is a fascinating, thoughtful, and inspiring guide to a marvelous form of literature: the short novel. You can dip into this book anywhere you like, but I found myself reading it cover-to-cover, delighting in discovering new works while also revisiting many of my favorites. GREAT SHORT BOOKS is itself a great book—for those who are over-scheduled but want to expand their reading and for those who will simply delight in spending time with a passionate fellow reader who on every page reminds us why we need and love to read.”

–Will Schwalbe, New York Times bestselling author of THE END OF YOUR LIFE BOOK CLUB

“This is the book that you didn’t know you really needed. I began digging into this book as soon as I got it, and it was such a delight to read beautiful prose, just a sip at a time, with Kenneth Davis’ notes to give me context and help me more fully appreciate the stories. Keep this book near your bed or on your coffee table. It will be read and loved.”

–Celeste Headlee, journalist and author of WE NEED TO TALK and SPEAKING OF RACE

Recording audio book of Great Short Books (Sept. 2022) Photo by Katherine Cook

From hard-boiled fiction to magical realism, the 18th century to the present day, Great Short Books spans genres, cultures, countries, and time to present a diverse selection of acclaimed and canonical novels—plus a few bestsellers. Like browsing in your favorite bookstore, this eclectic compendium is a fun and practical book for any passionate reader hoping to broaden their collection— or anyone who is looking for an entertaining, effortless reentry into reading.

Listen to a sample of the audio book of Great Short Books

And Indie booksellers weigh in:

“Need something grand, something classic, uh…. something short to read, but don’t know where to start? Check out Kenneth Davis’s guide to Great Short Books and you’ll soon find just the right tale to delight your literary palate. For each suggestion, Davis gives us first lines, a plot summary, an author’s bio, a reason for reading it, and, finally, what you should read next from the author’s canon. Pick up a copy… you’ll be glad you did. You’re welcome!”—Linda Bond, Auntie’s Bookstore (Spokane, WA)

“Kenneth Davis has presented the perfect solution for too many books, not enough time—a collection of exceptional short books perfect for reading in a society seemingly without any free time. Many of the books may be familiar by name, some are obscure, some even forgotten, but all belong in the canon of superb literature. He teases with a brief synopsis and explains why each book deserves attention. An absolutely intriguing bonus is a short biographical sketch of each author, many of whom had fascinating but traumatic lives. It is the perfect book to provide comfort literature for busy readers.”—Bill Cusumano, Square Books (Oxford, Miss.)

More early reviews from readers at NetGalley.com

“GREAT SHORT BOOKS is a wonderful, breezy but deep look at the outstanding short books of the last 150 years. Kenneth C. Davis is a genius at summarizing each book and making the reader want to read said book post haste. This is a book I didn’t know the world needed but the world did.” –Tom O., reviewer

“…an incredibly valuable tool for book clubs and readers everywhere! Some authors/titles are well-known and others will be new discoveries….HIGHLY RECOMMENDED for any book group looking to find new titles or any reader who wants to know what to read next.” –Ann H. reviewer

“I found over a dozen new authors or titles I want to now read that were included in his main list, and the Further Reading at the end of each chapter and at the end of the volume itself.

As others have suggested, this is a great tool for Book Clubs!

Not Lit Crit, it is mostly focused on necessary, just-the-facts-mam information on one person’s reading of short books over a year. Well worth a read, and great for browsing!” –Stephen B., Librarian“What better way to introduce new readers to more than 50 ‘short’ books. This handy book is full of non-spoiler descriptions and cultural context that situate these stories within our world.” –Kelsey W., librarian

S0urce: Great Short Books via NetGalley

I can’t wait to start talking about this book with readers everywhere.

Teachers, Librarians, Book Clubs and Other Learning Communities:

Invite me for a visit to your school, classroom, library, historical group, book club or conference.

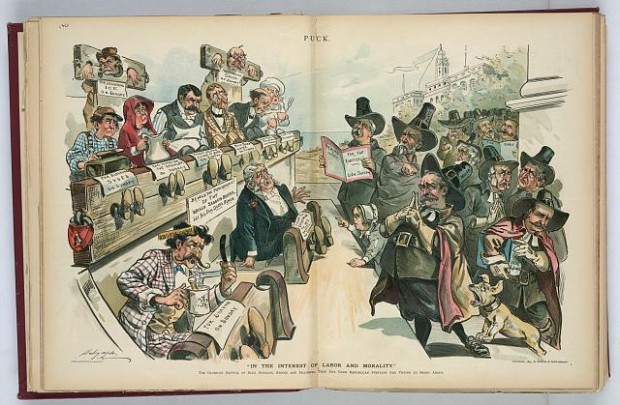

“In the interest of labor and morality” (1895: Image Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print)

(12.07.2025 revision of a post first published 12.11.2o13. But it never gets old.)

Fortunately, the so-called “War on Christmas” seems to have disappeared.

Proclaiming a secular assault on the religious significance of the holiday has been a seasonal tradition, just like the Macy’s Parade with Santa Claus. Claiming that “Happy Holidays” or “Season’s Greetings” instead of “Merry Christmas” was a betrayal of Christian America became a staple of conservative talk show hosts and part of America’s political culture wars.

The basic premise: Christmas is under attack by Grinch-y atheists and secular humanists who want to remove any vestige of Christianity from the public space. Any criticism of public displays devoted to religious symbols –mangers, crosses, stars — was seen by these folks as part of a wider attack on “Christian values” in America. Mass market retailers who substituted “Happy Holidays” for “Merry Christmas” were part of the conspiracy to “ruin Christmas.”

But in fact, most religious displays are not banned in America. Courts simply direct that one religion cannot be favored over another under the Constitutional protections of the First Amendment. Christmas displays are generally permitted as long as menorahs, Kwanzaa displays, and other seasonal symbols are also allowed.

In other words, the “War on Christmas” is pretty much a phony war. But where did this all start?

The first laws against Christmas celebrations and festivities in America came during the 1600s –from the same wonderful folks who brought you the Salem Witch Trials — the Puritans. (By the way, H.L. Mencken once defined Puritanism as the fear that “somewhere someone may be happy.”)

“For preventing disorders, arising in several places within this jurisdiction by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other communities, to the great dishonor of God and offense of others: it is therefore ordered by this court and the authority thereof that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offence five shilling as a fine to the county.”

–From the records of the General Court,

Massachusetts Bay Colony

May 11, 1659

The Founding Fathers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were not a festive bunch. To them, Christmas was a debauched, wasteful festival that threatened their core religious beliefs. They understood that most of the trappings of Christmas –like holly and mistletoe– were vestiges of ancient pagan rituals. More importantly, they thought Christmas — the mass of Christ– was too “popish,” by which they meant Roman Catholic. These are the people who banned Catholic priests from Boston under penalty of death.

This sensibility actually began over the way in which Christmas was celebrated in England. Oliver Cromwell, a strict Puritan who took over England in 1645, believed it was his mission to cleanse the country of the sort of seasonal moral decay that Protestant writer Philip Stubbes described in the 1500s:

‘More mischief is that time committed than in all the year besides … What dicing and carding, what eating and drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used … to the great dishonour of God and the impoverishing of the realm.’

In 1643, Parliament banned Christmas celebrations.

“The Puritans sought to turn Christmas into a fast day, with an act of Parliament in 1643 declaring that it should be observed ‘with the more solemn humiliation because it may call to remembrance our sins, and the sins of our forefathers who have turned this Feast, pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him, by giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights.’ Two years later, the Directory of Public Worship was unequivocal that feasts such as Christmas had no warrant in scripture.”

–Bruce Gordon, “The Grinch That Didn’t Steal Christmas”

Attending mass was forbidden. Under Cromwell’s Commonwealth, mince pies, holly and other popular customs fell victim to the Puritan mission to remove all merrymaking during the Christmas period. To Puritans, the celebration of the Lord’s birth should be day of fasting and prayer.

In England, the Puritan War on Christmas lasted until 1660. In Massachusetts, the ban remained in place until 1687.

So if the conservative broadcasters and religious folk really want a traditional, American Christian Christmas, the solution is simple — don’t have any fun.

My latest work, The World in Books (Scribner, 2024) includes an entry on the gospel of Luke, which commences with one version of the Nativity. The history behind Christmas is also told in Don’t Know Much About® The Bible.

And read my article on religion in America, “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance” (Smithsonian)

Read more about the Puritans in Don’t Know Much About® History and America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

As the fourth Thursday in November approaches, our country is gearing up for a diet-busting meal to celebrate those somber folks in clunky shoes and buckled hats who sailed to the New World aboard the Mayflower. The Pilgrims wore black clothing, right? And ate turkey with the Native Americans, remember? And their peaceful relations with the Indians was long lasting, correct?

Well, not exactly. But first the parade.

•When did Macy’s start its iconic parade?

The Macy’s tradition began in 1924 (Philadelphia’s is older) and started as a “Christmas parade” –stepping off in Harlem and ending at Herald Square with Santa Claus enthroned as “King of the Kiddies.” (New York Times)

Santa’s Sleigh 1924 Macy’s Christmas Parade https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Santa%27s_Sleigh_(1924).webp

Macy’s employees were the marchers –there were floats but no balloons yet—and many of them were recent European immigrants. The idea of a grand parade was an old European tradition. This underscores the notion that Thanksgiving is a holiday of immigrants. And over the years, many cultures and nationalities have contributed to the evolution of Thanksgiving.

The parade has only been interrupted three times –all during World War II (in 1943, 1943, and 1944) due to rationing and shortages.

If you say religious freedom, you get only partial credit. The Pilgrims were an offshoot sect of Puritans, people who were challenging the Church of England and the English monarchy itself. But the Pilgrims went another step—they wanted to separate from the Church of England completely. These Separatists left England to take refuge in Holland. Unhappy there, they set up a company that would start a new colony in America where the Virginia colony had been established in 1606.

The Mayflower Pilgrims did not call themselves “pilgrims.” They referred to themselves as “saints” or “First Comers.” Only later did William Bradford call them Pilgrims. But not even all of the passengers on the Mayflower were Pilgrims. Of 102 people on board, only about 50 were Pilgrims. The others were members of the Church of England who had signed on simply as laborers, soldiers or those looking to gain property in the “New World.” The Pilgrims called them “Strangers.”

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth” (1914) By Jennie A. Brownscombe (Public Domain, Source Wikimedia)

Before the Mayflower landed, it became clear that the Saints and the Strangers didn’t see eye to eye. To preserve order in the colony, the men aboard the ship agreed to a rudimentary system of democracy under the so-called Mayflower Compact; it was, in essence, the first written Constitution in American history. (Sorry ladies, only adult males could vote.)

IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620.

[The Mayflower Compact: Complete text and signers Source: Yale Law School Avalon Project

One child named Oceanus was born during the voyage. Another named Peregrine was born on board after the Mayflower landed. And one in six Americans can still claim a relative who came aboard the Mayflower. Among them are Presidents John Adams and John Quincy Adams, Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, James Garfield, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and both Bushes.

One piece of the Pilgrim story is that two different indigenous men came to the Pilgrim camp and spoke English. The first was Samoset. He returned a few days later with Squanto (probably a shortened version of Tisquantum). Squanto had been taken captive by an English sea captain, sold into slavery in Spain, and later made his way to London where he learned to speak English. His value as an interpreter was recognized and he returned to Massachusetts on an English ship only to discover his entire village had been wiped out—probably by disease introduced by Europeans. That village was the future site of Plymouth and he indeed helped the English settlers survive their difficult first year.

Nothing, literally. To the Pilgrims, a true day of thanksgiving simply meant a day of prayer and fasting –not what most of us have in mind when turkey day comes around.

What we now call “Thanksgiving” was in fact a harvest festival for the Pilgrims who celebrated in October –not November—1621. Those Pilgrims were mostly grateful just to be alive –half of their company had died during the bleak first winter in Massachusetts after they had landed at Plymouth in December 1620. (And by the way, there was no mention of Plymouth Rock at the time. That’s clearly a notion cooked up more than a hundred year later.)

Yes, sort of. There was turkey, but not the one we know and love. It was wild turkey (the animal, not the beverage). The menu for this major feast was a colonial era surf-and-turf which included ducks, geese, cod, salmon, lobster, mussels, eels and clams, along with wild onions to make sallet (salad) and vegetables, including pumpkins (but no pie) and “crane berries” (but no cranberry jelly). Dessert would have been cornmeal breads and puddings.

In addition to about fifty Pilgrims, unexpected company arrived. About ninety Wampanoag warriors showed up with their chief Massasoit. The Indians went out like good guests and brought back plenty of venison, which was added to the menu. The harvest feast then lasted three days.

The peace and good will of that celebration lasted about a generation. First, the English settlers fought a brutal war against the nearby Pequot, wiping them out in 1637. Then, in 1676, Massasoit’s son Metacom – known as King Philip—led the Wampanoag in a war of survival against the English. (“King Philip’s War”). This bloody conflict nearly wiped out the colonists who ultimately prevailed. Metacom’s head was placed on a pole; his wife and son – grandson of the chief who came to dinner in 1621—were sold into slavery. The Wampanoag and other native nation were decimated.

During that war, a settler named Mary Rowlandson was taken captive and spent three months traversing the Massachusetts wilderness with Metacom. She later wrote an account of her captivity, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God (1682), which has been described as the first bestselling book by a woman in America. (Rowlandson’s book is among the 52 works in my new book, The World in Books.)

#image_title

• What is the difference between a Pilgrim and a Puritan?

The Puritans wanted to “purify” the Church of England –that is to get rid of any vestige of Roman Catholicism. This was not a polite religious argument over how to say your prayers, but a phase of the Protestant Reformation that eventually led to a bloody English Civil War and the beheading of King Charles I in 1649.

The Pilgrims were more radical and wanted to separate from the Church of England which is why they were banished.

While the Pilgrims arrived first, they were soon followed by a mass wave of Puritan emigration during the 1620s, and the Pilgrims were eventually absorbed into the Puritan-dominated Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Thanksgiving was first celebrated as an official holiday in 1777, to mark the patriot victory at Saratoga in the Revolutionary War. When Washington later tried to proclaim a Thanksgiving Day, some in Congress complained that he had no right to make such a proclamation.

Gradually Presidents routinely proclaimed days of “thanksgiving,” but the custom died out in the 19th century. In 1837, a writer and magazine editor named Sarah Josepha Hale began a campaign to reinstate the holiday. Hale was also the author of the poem, “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

At Hale’s persistent urging, Abraham Lincoln finally proclaimed a national holiday of Thanksgiving in October 1863, to be marked in November.

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American People. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens. And I recommend to them that while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty Hand to heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity and Union.

[Abraham Lincoln’s Proclamation of Thanksgiving, Source: American Battlefield Trust]

• What happened on Thanksgiving 1864?

Lincoln issued a second proclamation the following year while General Grant’s army was besieging Petersburg, Virginia.

“Around the same time, the heads of Union League clubs – Theodore Roosevelt’s father among them – led an effort to provide a proper Thanksgiving meal, including turkey and mince pies, for Union troops. As the Civil War raged on, four steamers sailed out of New York laden with 400,000 pounds of ham, canned peaches, apples and cakes – and turkeys with all the trimmings. They arrived at Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters in City Point, Va., then one of the busiest ports in the world, to deliver dinner to the Union’s “gallant soldiers and sailors.” This Thanksgiving delivery was an unprecedented effort – a huge fund-raising and food-collection drive. One soldier said, ‘It isn’t the turkey, but the idea we care for.’”

[“How the Civil War Created Thanksgiving” New York Times “Disunion” blog]

• What is “Franksgiving?”

During the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the date to the third Thursday in November at the request of retailers who wanted to extend the holiday shopping season. Republicans balked at this break with tradition and there were two Thanksgivings that year. In 1941, with individual state governors declaring separate thanksgiving days, Congress declared a national holiday and it was fixed on the fourth Thursday in November, where it remains.

• What made Football and Thanksgiving an American tradition?

The tradition of college football dated to 1876 when Yale and Princeton played. It was transferred to the pros when the NFL formed. The Detroit Lions played a game in 1934 that was televised nationally, establishing the NFL tradition of Thanksgiving games in Detroit. The Dallas Cowboys were later awarded a second Thanksgiving Day game.

•Were the Mayflower’s passengers the first “Pilgrims” in America?

The Spanish in the Caribbean, Mexico, the American southeast, Central and South America all got to America before the Pilgrims. So did the Jamestown colonists in 1607 in Virginia. Remember 1619. And they all probably had harvest feasts before the Pilgrims too. But the true first Pilgrims in American were a group of French colonists who landed in Florida in 1654, Huguenots, or French Protestants, they came to American for the same reason the Pilgrims would more than fifty years later –to escape persecution in Catholic France.

Settling near modern day Jacksonville, they built Fort Carolina. One year later in 1655, a Spanish fleet arrived and established St. Augustine. Their purpose was simple –to eliminate the French “heretics” in Spanish Florida. In a series of massacres, hundreds of French Protestants were put to the sword by the Spanish—ending America’s first “pilgrim” experiment in a sectarian bloodbath.

Read more about this episode in America’s Hidden History.

On the holiday calendar, once we leave Veterans Day behind, we round towards Thanksgiving — perhaps America’s most beloved, widely shared, and mythologized celebration.

But this reminds me of the fact that Abraham Lincoln’s first Thanksgiving proclamation came in 1863. Lincoln called for a day of Thanksgiving in the midst of the Civil War. The date fell shortly after Lincoln offered the Gettysburg Address.

It must have felt like there was little to celebrate– or to be grateful for.

Like the Macy’s parade, this is my Thanksgiving tradition. I post two articles about the holiday with some “Hidden History” that appeared on the Op-Ed page of the New York Times.

So here’s something to read–either before or after the feast.

The first article, from 2008, is called “A French Connection” and tells the story of the real first Pilgrims in America. They were French. In Florida. Fifty years before the Mayflower sailed. It did not end with a happy meal. In fact, it ended in a religious massacre.

Illustration by Nathalie Lété in the New York Times

TO commemorate the arrival of the first pilgrims to America’s shores, a June date would be far more appropriate, accompanied perhaps by coq au vin and a nice Bordeaux. After all, the first European arrivals seeking religious freedom in the “New World” were French. And they beat their English counterparts by 50 years. That French settlers bested the Mayflower Pilgrims may surprise Americans raised on our foundational myth, but the record is clear.

The complete story can be found in America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

The second is “How the Civil War Created Thanksgiving” (2014) and tells the story of the Union League providing Thanksgiving dinners to Union troops.

Of all the bedtime-story versions of American history we teach, the tidy Thanksgiving pageant may be the one stuffed with the heaviest serving of myth. This iconic tale is the main course in our nation’s foundation legend, complete with cardboard cutouts of bow-carrying Native American cherubs and pint-size Pilgrims in black hats with buckles. And legend it largely is.

In fact, what had been a New England seasonal holiday became more of a “national” celebration only during the Civil War, with Lincoln’s proclamation calling for “a day of thanksgiving” in 1863.

Enjoy them both.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

[This is a revised version of a post originally written for Veterans Day in 2011. The meaning still applies. In 2025, the holiday is observed on Tuesday November 11.]

“THE ELEVENTH HOUR OF THE ELEVENTH DAY OF THE ELEVENTH MONTH”

Taken at 10:58 a.m., on Nov. 11, 1918, just before the Armistice went into effect; men of the 353rd Infantry, near a church, at Stenay, Meuse, wait for the end of hostilities. (SC034981)

On Veterans Day, this is a reminder of what the day once meant and what it should still mean.

That was the moment at which World War I –then called THE GREAT WAR– largely came to end in 1918, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

One of the most tragically senseless and destructive periods in all history came to a close in Western Europe with the Armistice –or end of hostilities between Germany and the Allied nations — that began at that moment. Some 20 million people had died in the fighting that raged for more than four years since August 1914. The formal end of the war came with the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

Today, it is important to recognize the role of that treaty and the war in the rise of some of the most murderous dictators in history. That history is told in my book, Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy.

Besides the war casualties, an estimated 100 million people died during the war of the Spanish flu, a worldwide pandemic that was completely linked to the war and had an impact on its outcome. That is the subject of my recent book, More Deadly Than War:The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War.

The date of November 11th became a national holiday of remembrance in many of the victorious allied nations –a day to commemorate the loss of so many lives in the war. And in the United States, President Wilson proclaimed the first Armistice Day on November 11, 1919. A few years later, in 1926, Congress passed a resolution calling on the President to observe each November 11th as a day of remembrance:

Whereas the 11th of November 1918, marked the cessation of the most destructive, sanguinary, and far reaching war in human annals and the resumption by the people of the United States of peaceful relations with other nations, which we hope may never again be severed, and

Whereas it is fitting that the recurring anniversary of this date should be commemorated with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations; and

Whereas the legislatures of twenty-seven of our States have already declared November 11 to be a legal holiday: Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring), that the President of the United States is requested to issue a proclamation calling upon the officials to display the flag of the United States on all Government buildings on November 11 and inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches, or other suitable places, with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

Of course, the hopes that “the war to end all wars” would bring peace were short-lived. By 1939, Europe was again at war and what was once called “the Great War” would become World War I. With the end of World War II, there was a movement in America to rename Armistice Day and create a holiday that recognized the veterans of all of America’s conflicts. President Eisenhower signed that law in 1954. (In 1971, Veterans Day began to be marked as a Monday holiday on the third Monday in November, but in 1978, the holiday was returned to the traditional November 11th date).

Today, Veterans Day honors the duty, sacrifice and service of America’s millions of veterans of all wars, unlike Memorial Day, which specifically honors those who died fighting in America’s wars. In 2025, there are some 15.8 million veterans in the United States. That number is declining significantly each year. According to Census data, in 2023, almost half of veterans were 65 or older, while nearly a third were 75 or older; in 2013, 47.3% were 65 and older. 8.3% of veterans in 2023 were 34 or younger. Almost ten percent of veterans are women. (Source: USAFacts)

We should remember and celebrate all those men and women. But lost in that worthy goal is the forgotten meaning of this day in history –the meaning which Congress gave to Armistice Day in 1926:

to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations …

inviting the people of the United States to observe the day … with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

The Library of Congress offers an extensive Veterans History Project.

Read more about World War I and all of America’s conflicts in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

I discuss the role of Americans in battle in more than 240 years of American history in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah (Hachette Books and Random House Audio).

MORE DEADLY THAN WAR: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War was published in May 2018. Strongman was published in 2020.

(Video directed and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2015)

When I was a kid in the early 1960s, the autumn social calendar was highlighted by the Halloween party in our church. In these simpler day, the kids all bobbed for apples and paraded through a spooky “haunted house” in homemade costumes –Daniel Boone replete with coonskin caps for the boys; tiaras and fairy princess wands for the girls. It was safe, secure and innocent.

The irony is that our church was a Congregational church — founded by the Puritans of New England. The same people who brought you the Salem Witch Trials.

Here’s a link to a history of those Witch Trials in 1692.

Rooted in pagan traditions more than 2000 years old, Halloween grew out of a Celtic Druid celebration that marked summer’s end. Called Samhain (pronounced sow-in or sow-een), it combined the Celts’ harvest and New Year festivals, held in late October and early November by people in what is now Ireland, Great Britain and elsewhere in Europe. This ancient Druid rite was tied to the seasonal cycles of life and death — as the last crops were harvested, the final apples picked and livestock brought in for winter stables or slaughter. Contrary to what some modern critics believe, Samhain was not the name of a malevolent Celtic deity but meant, “end of summer.”

The Celts also saw Samhain as a fearful time, when the barrier between the worlds of living and dead broke, and spirits walked the earth, causing mischief. Going door to door, children collected wood for a sacred bonfire that provided light against the growing darkness, and villagers gathered to burn crops in honor of their agricultural gods. During this fiery festival, the Celts wore masks, often made of animal heads and skins, hoping to frighten off wandering spirits. As the celebration ended, families carried home embers from the communal fire to re-light their hearth fires.

Getting the picture? Costumes, “trick or treat” and Jack-o-lanterns all got started more than two thousand years ago at an Irish bonfire.

Christianity took a dim view of these “heathen” rites. Attempting to replace the Druid festival of the dead with a church-approved holiday, the seventh-century Pope Boniface IV designated November 1 as All Saints’ Day to honor saints and martyrs. Then in 1000 AD, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to remember the departed and pray for their souls. Together, the three celebrations –All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls Day– were called Hallowmas, and the night before came to be called All-hallows Evening, eventually shortened to “Halloween.”

And when millions of Irish and other Europeans emigrated to America, they carried along their traditions. The age-old practice of carrying home embers in a hollowed-out turnip still burns strong. In an Irish folk tale, a man named Stingy Jack once escaped the devil with one of these turnip lanterns. When the Irish came to America, Jack’s turnip was exchanged for the more easily carved pumpkin and Stingy Jack’s name lives on in “Jack-o-lantern.”

Halloween, in other words, is deeply rooted in myths –ancient stories that explain the seasons and the mysteries of life and death.

(Originally posted in 2022; Revised and updated September 30, 2025)

Book censorship is as American as apple pie, slavery, and lynching.

This post offers a brief overview of book banning in America. As teachers and librarians are fired, service academy libraries are purged, and free speech is under assault, the subject is more important than ever.

UPDATE (10/1/2025)

“Restrictions on books in public schools have become ‘rampant and common,’ according to a new report by the free speech organization PEN America, so frequent in some states that they are now considered ‘routine and expected part of school operations.'” (“‘Rampant Book Bans’ Are Being Taken for Granted,” NEW YORK TIMES, October 1, 2025)

Banned Books Week 2025 is marked from October 5-11 in 2025

“The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.”

American Library Association “Freedom to Read” Statement, first issued on June 25, 1953.

Robin Hood was a Commie.

That, at least, is what an Indiana state textbook commissioner thought back in 1953. This official called for schools to ban books mentioning Robin Hood for the simple reason that Robin and his Merry Men robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Their antics reeked suspiciously of godless Socialism.

It is easy to laugh off this overlooked history as an amusing bit of trivia. Except the Hoosier state assault on Robin Hood was part of a larger nationwide effort to ban books and suppress intellectual freedom. It was led by Senator Joseph McCarthy during the anti-Communist “witch hunts.” It targeted books, writers, and libraries both at home and around the world. And it holds pointed lessons about safeguarding democracy from the forces threatening it today.

After the 1947 blacklisting of the “Hollywood Ten” screenwriters by the House Un-American Affairs Committee (HUAC), Senator McCarthy emerged as the face and unrelenting voice of a crusade against Communist influences in America. In 1950, McCarthy claimed to possess an extensive list of Communists who worked in the State Department. Launching his war on alleged Communist infiltrators as chairman of a Senate committee on government operations, McCarthy was abetted by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. To be labeled a Communist was an accusation from which there was no escape. Claims of innocence or invoking the Fifth Amendment were tantamount to confession.

Set against the Korean War begun in 1950, and with the convictions of Alger Hiss that year for perjury over espionage and the Rosenbergs in 1951 for atomic spying, America’s fear of Communism spread like wildfire. Gaining an army of rabid followers, McCarthy’s crusade to root out subversives widened to focus intently on libraries, which were pressured to purge their collections of works by Marx. By 1952, the New York Times described a pervasive wave of educational book censorship in America. Around the country, self-appointed local committees— “volunteer educational dictators” in the words of one librarian—were coercing librarians to remove books considered “un-American,” the Times found.

This anti-Communist juggernaut was not only steam-rolling domestic libraries. McCarthy sent it on a road trip. In April 1953, McCarthy’s underlings, attorney Roy Cohn and associate David Schine, were dispatched to Europe. Part of their mission was to scrutinize U.S. Information Service libraries, created to provide war-ravaged countries with American books. McCarthy claimed that these collections held thousands of works by Communists. Targeting suspect authors, just as Hollywood had been purged of “Red” screenwriters, Cohn and Schine succeeded in intimidating foreign service officials. No fires were set, but titles by Dashiell Hammett, Lillian Hellman, and Howard Fast, among others, were pulled from the shelves.

Inaugurated in January 1953, President Eisenhower was hesitant to challenge McCarthy. But he discreetly fired back. He told a Dartmouth commencement audience in June of that year:

“Don’t join the book burners. Don’t think you are going to conceal faults by concealing evidence that they ever existed. Don’t be afraid to go in your library and read every book, as long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency.”

–President Eisenhower, “Remarks at the Dartmouth College Commencement”

Unfortunately, Eisenhower’s defense of reading was less than full-throated. Ultimately, his State Dept. folded to McCarthy’s men.

“Only reckless men, under these conditions, could choose to take steps offensive to McCarthy since the President and the Secretary [of State John Foster Dulles] have rarely backed up their subordinates whom McCarthy has singled out for attack.”

But America’s librarians were not about to be silenced. Despite the stale caricature of an old lady in a bun shushing the patrons, many librarians spoke out, daringly, given the nation’s fearful mood and threats to their jobs. Responding to this mounting pressure, the American Library Association (ALA), in concert with the American Association of Publishers, issued on June 25, 1953 a “Freedom to Read” statement –since revised several times—that begins, “The freedom to read is essential to our democracy. It is continuously under attack.”

Unfortunately, the ALA was right then—and now. Ike’s “book burners” are back—or perhaps it is more accurate to say they never left. Across America, a concerted effort to purge school and public libraries of “offensive” literature has found new vigor and a louder voice. There is a long history of attempts to rid libraries of books considered objectionable—it is the reason the ALA launched its annual Banned Books Week in 1982 ago to highlight local challenges to books. But these perennial community-level attempts to challenge books deemed “subversive” or “indecent” have reached a new level of intensity.

Currently, in America’s riven political ecosystem, the hyper-charged urge to purge has been fused with anger over vaccinations and mask mandates and the assault on teaching any American history that doesn’t fit a suitably patriotic mold. In such states as Florida, Texas, and Virginia, the backlash has grown intense and been wrapped in the pretense of giving parents “control” over their children’s education. The bullseye has moved from Robin Hood, The Communist Manifesto, and The Catcher in the Rye to a new set of targets. Many of the books now under fire deal with race, slavery, gender issues, and of course, sexuality.

Raising the fever pitch are books exploring gay relationships and gender identity. In November 2021, a Virginia school board member was quoted in press reports as saying, “I think we should throw those books in a fire.”In February, a Tennessee pastor went further, leading a book burning that saw Harry Potter and Twilight consigned to the flames—both among the usual suspects in recent book bans and challenges.

We’ve seen these flames before. In fiction, they raged in Ray Bradbury’s dystopic Fahrenheit 451 in which “firemen” burn outlawed books. Bradbury’s 1953 novel was written in large part as a reaction to the ongoing purges under McCarthy and his followers.

But these flames have also roared more frighteningly in fact. Book burnings are actually older than books, dating to ancient times in Greece and China. After Gutenberg’s printing revolution, the Vatican created the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a catalog of banned books, some of which were burned, sometimes along with their authors—like Giordano Bruno in 1600.

Most notoriously in pre-World War II Germany, some 25,000 “un-German” books were consigned to Nazi bonfires in May 1933. Targeted by Hitler’s loyal disciples were works by German Jews and Marx, Freud, and Einstein. Books by German novelists Thomas Mann and Eric Maria Remarque—author of the World War I classic All Quiet on the Western Front— went into the flames along with such American writers as Ernest Hemingway, Jack London, and Helen Keller.

Book Burning May 10, 1933 Image courtesy US Holocaust Memorial Museum https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/book-burning

Can it happen here? It has.

Nearly a century before the Nazi book burnings, a concerted effort to flood the slaveholding states with abolitionist literature was met with fire. In the summer of 1835, an angry mob raided a Charleston, South Carolina post office and consigned thousands of abolitionist pamphlets to a bonfire. The book burning was topped off with an effigy of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison being set ablaze. Garrison was lucky. Tragically, abolitionist publisher Elijah Lovejoy was not. Two years later, a mob intent on burning anti-slavery literature in Alton, Illinois murdered Lovejoy as he tried to defend his presses. A century later, in 1939, California growers burned Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Grapes of Wrath.

Scrubbing the nation’s public square of “offensive” materials and torching books—despite the protections in the Bill of Rights—are as American as apple pie, lynch mobs, and burning crosses.

But there’s something new in the equation. The latest wave of book suppression is not simply about “subversion” or “dirty words.” Scratch the surface of recent book bans and it is clear that the assault on free expression cannot be separated from the larger Orwellian effort to sanitize American history, de-legitimize literature by gay writers and people of color, and undermine democracy.

On orders from the Pentagon, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point has led to canceled classes and banned books.

“A history professor who leads a course on genocide was instructed not to mention atrocities committed against Native Americans, according to several academy officials. The English department purged works by well-known Black authors, such as Toni Morrison, James Baldwin and Ta-Nehisi Coates, the officials said.” (New York Times, May 8, 2025)

A similar purge took place at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md.:

“Maya Angelou’s seminal autobiography, ‘I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings,’ and books on the Holocaust were included on the Navy’s list of 381 books that were removed from the U.S. Naval Academy’s Nimitz Library on the Annapolis, Md., campus this week because their subject matter was seen as being related to so-called diversity, equity and inclusion topics.” (New York Times, April 4, 2025)

This revitalized onslaught carries the distinct whiff of white, Christian nationalism. This is the racial, cultural, and political ideology that once reared its head as nineteenth-century Nativism, the reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, and the America Firsters of the 1930s.

Claiming that the United States is a “Christian nation,” this strand of anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic American DNA is older than the nation itself. Time has not diminished its power. Now adding “globalists” to their enemies list, white Christian nationalism has been tied to the Charlottesville rioters who chanted “You will not replace us” and the January 6 insurrection by experts who study the movement.

America has no monopoly on this historically powerful faction. A form of white Christian nationalism, with its claims of racial superiority, certainly fed Hitler’s rise in Germany.

And that is why this revived wave of book suppression is a piece of a much larger development. The reason that Maus, a Pulitzer-Prize winning graphic novel-memoir about the Holocaust, was ostensibly pulled from schools in Tennessee was for some of its language and a discreet cartoon illustration of the author’s mother—an Auschwitz survivor—naked in the bathtub where she had committed suicide. But its critics apparently sought a kinder, gentler discussion of the Holocaust, although any attempts to soften that history tiptoe dangerously toward denialism. This is how history goes down 1984’s “Memory Hole,” as George Orwell knew.

Banning books, legislating against “divisive concepts” in history class, and purging diversity all come straight from the playbook of the Strongman. He knows the power of the pen. Books make us think. Literature cultivates the free mind. Writers are truth-tellers. In 1917, Soviet leader Lenin ordered a “Decree on Press” threatening closure of publications critical of the Bolsheviks. Authoritarians know the danger posed by truth. And they are more than willing to use sword and flame to cut it down.

The question is what can we do about it?

“The antidote to authoritarianism is not some form of American authoritarianism,” Cooper Union librarian David K. Berninghausen told the Times in 1952. “The antidote is free inquiry.”

When Robin Hood was threatened by a textbook commissioner in 1953, some Indiana State University students fought back. Five of them gathered chicken feathers, dyed them green, and spread them across campus. Their protest caught on at other colleges, including UCLA, where two hundred students dressed up as Sherwood Forest’s Merry Men for a Green Feather drop. A clever, well-aimed protest, the Green Feather movement broke no windows or legs. Robin Hood was spared.

But those more innocent days are gone. In the internet age, the lines are more sharply drawn, sides set in stone, and the stakes much higher.

That is why dumping some green feathers or wearing an “I READ BANNED BOOKS” t-shirt will not be enough for this moment. If we care, we must take to heart Ike’s advice and “read every book.” We must firmly resolve to read. But buying and reading Maus or Toni Morrison’s Beloved are only the first steps.

We have to make sure that others can read these books. We must be audacious in support of free libraries and vigorously support all teachers who want to encourage students to read, debate, and think for themselves. And we must vigilantly push back on politicians and schoolboards purging libraries of uncomfortable truths. A few loud voices dominating a schoolboard or town hall meeting do not a majority make. To allow a noisy minority to dictate what we read and teach is skating on that thin ice of totalitarian loyalty oaths typical of a Mussolini or Stalin.

On this final note, history is clear. When you have succeeded in marking a writer as “degenerate” or “immoral”—as the Nazis did—you have moved towards dehumanizing them. It is a few short perilous steps from censorship to suppression to a conflagration far worse. In Berlin, on the spot where Nazis threw books into a bonfire, there is a plaque citing German playwright Heinrich Heine’s 1820 words, which read in part: “Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”

The road to Hell is lit by burning books.

I am also linking to this article from American Libraries, a publication of the American Library Association; “Same Fight, New Tactics,” which offers tips for meeting challenges to books in libraries.

Here are some key organizations leading the fight against book bans and other forms of censorship:

National Coalition Against Censorship

American Library Association (ALA) Office of Intellectual Freedom (OIF)

ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) “What is Censorship?

© Copyright 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025 Kenneth C. Davis All rights reserved

(Reposted from 2014)

Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.

Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (“State of the Union”) December 3, 1861

It is not needed nor fitting here that a general argument should be made in favor of popular institutions, but there is one point, with its connections, not so hackneyed as most others, to which I ask a brief attention. It is the effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government. It is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor. This assumed, it is next considered whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent, or buy them and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far, it is naturally concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer is fixed in that condition for life.

Now there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed, nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer. Both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them are groundless.

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights.

Source and Complete text: Abraham Lincoln: “First Annual Message,” Read more about Lincoln, his life and administration and the Civil War in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the Civil Warand Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Labor Day became a federal holiday on September 3, 1894.

Read about the history of Labor Day in this post.

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)