John Adams, Second POTUS , official portrit (Source: White House Historical Association)

[UPDATED 9/28/2016]

On February 24, 1803 Chief Justice John Marshall delivered the unanimous opinion in Marbury v Madison.

Dust off your Civics books.

As the fight over Judge Garland as Antonin Scalia’s replacement on the Supreme Court absorbs the country, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has vowed to block any appointments by President Obama during his last year in office, it might help to look at history.

The simple fact is that the most consequential Supreme Court appointment in American history was made by a true “lame duck” President.

In its original sense, “lame duck” meant a president or other elected official whose successor had already been chosen.

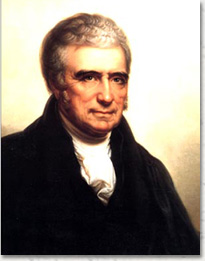

John Marshall Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

(Reproduction courtesy of the Supreme Court Historical Society)

On January 20, 1801, after it was certain that president John Adams would not return for a second term, Adams nominated his Secretary of State, John Marshall, to the post to replace ailing Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth.

At the time of this nomination, President Adams was a true “lame duck” president, soon to be replaced by Thomas Jefferson, following a drawn-out vote in the House of Representatives. It was clear that Jefferson’s party would control both the White House and the Senate. But Adams named Marshall, a staunch Federalist of his own party, who was confirmed on January 27, 1801, despite only six-weeks of legal training.

One of Marshall’s first and most significant decisions came in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison which established the power of federal courts to void acts of Congress in conflict with the Constitution.

It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. . . . Thus the particular phraseology of the constitution of the United States confirms and strengthens the principle, supposed to be essential to all written constitutions, that a law repugnant to the constitution is void. . . .

From Chief Justice Marshall’s decision in Marbury v. Madison

John Marshall went on to become the longest-serving and most influential chief justice in the history of the Supreme Court, hearing more than 1,000 cases and writing 519 decisions.

There have been more election year nominations, as discussed in this New York Times Op-Ed, “In Election Years, a History of Conforming Court Nominees.”

As John Adams himself said during the Boston Massacre Trial (1770)

“Facts are stubborn things.”