–Thomas Paine, The American Crisis (December 19, 1776)

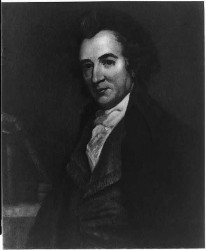

Thomas Paine ©National Portrait Gallery London copy by Auguste Millière, after an engraving by William Sharp, after George Romney oil on canvas, circa 1876

[Originally posted December 2020; revised 1/20/2025]

Thomas Paine was born in England on January 29, 1736 (in the Old Style; his birth-date is also listed as February 9, 1737 in the New Style). Thomas Paine’s essay Common Sense is widely credited with helping to rouse Americans to the patriot cause. Its sales were extraordinary at the time; given today’s American population, current day sales would reach some 60 million copies.

Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

-Thomas Paine Common Sense

Common sense; addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following interesting subjects (Library of Congress)

The pamphleteering Paine is best known for Common Sense, which appeared in January 1776 and The Crisis — first published on December 19 1776 — among other works that supported the cause of independence. But after the Revolution, Paine returned to his native England and later went to France, then in the throes of its Revolution.

Paine was caught up in the complex politics of the bloody Revolution there, eventually winding up in a French prison cell, facing the prospect of the guillotine. After eventually being freed, Paine wrote an open letter in 1796 angrily denouncing President George Washington for failing to do enough to secure his release.

“Monopolies of every kind marked your administration almost in the moment of its commencement. The lands obtained by the Revolution were lavished upon partisans; the interest of the disbanded soldier was sold to the speculator…In what fraudulent light must Mr. Washington’s character appear in the world, when his declarations and his conduct are compared together!”

Source: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

This was a serious case of bridge-burning and Paine swiftly fell from grace in America. But apart from dissing the Father of the Country, Paine had also fallen from favor for his most famous work after Common Sense. In 1794, he had published The Age of Reason (Part I), a deist assault on organized religion and the errors of the Bible.

In it, Paine had written:

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.

All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

(Source: USHistory.org)

After returning to the United States, which owed so much to him, Paine was regarded as an atheist and was abandoned by most of his friends and former allies. He died in disgrace, an outcast from the United States he had helped create. The Quaker church he had rejected refused to bury him after he died in Greenwich Village (New York City) in 1809. He was buried on his farm in New Rochelle, New York. A handful of people attended his funeral.

An admirer brought his remains back to England for reburial there, but they were lost.

Today he is honored in New York City by a small park named in his honor.

“This park in the heart of New York City’s civic center is named for patriot, author, humanitarian, and political visionary Thomas Paine (1737-1809). The land that is now Thomas Paine Park was once part of a freshwater swamp surrounded, ironically, by three former British prisons for revolutionaries.

His most famous work, Rights of Man (1791), was written after the French Revolution and proposes that government is responsible for protecting the natural rights of its people. Many of Paine’s ideas were strikingly far sighted. He advocated for the abolition of slavery, defended freedom of thought and expression, and proposed an association of nations to avert the spread of conflicts.”

You can read more about Thomas Paine, his relationship with Washington and his ultimate fate in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

Paine’s book, The AGE OF REASON, is among 52 short works of nonfiction included in THE WORLD IN BOOKS.