[Post updated 6/25/2023]

This is the sixth in a series of posts about the men who signed the Declaration of Independence and what became of them. The series begins here. Or follow the series here.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

As the nation goes through an examination of the role slavery played in American History, it is important to recognize its place in Philadelphia in 1776. You cannot teach American History without acknowledging that slavery was central to the founding of the country. And talking about the men who signed the Declaration is one way to do that. The Yes after a name means the Signer enslaved people; No means he did not.

In this group: More wealthy planters and a couple of very wealthy New York merchants.

•Richard Henry Lee (Virginia) A 41-year-old planter from a prominent Virginia family –his younger brother Francis Lightfoot (See previous post) was also there– Lee deserves more acclaim than he usually gets. A “great orator,” said John Adams, Lee introduced the resolution for independence. He left Congress to attend to state business in Virginia and didn’t vote for the resolution or the Declaration, which he signed later in the summer of 1776.

Richard Henry Lee National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Duncan Lee and his son, Gavin Dunbar Lee

He was one of the few signers to actually serve with a Virginia militia unit. He remained in politics after the war, becoming a vocal opponent of the Constitution but an advocate for the Bill of Rights. He was elected to the U.S. Senate but resigned in ill health and died at age 62 in 1794. YES

•Francis Lewis (New York) A native of Wales, he was a 63-year-old merchant at the time of the signing, a key supporter of George Washington, but was instructed not to vote for the Declaration by New York. He then signed in August. During the war, his wife was imprisoned by the British and died shortly after her release, leaving Lewis grief-stricken. He died in 1802 at age 89, was buried in an unmarked grave at Manhattan’s Trinity Church, and now, curious New Yorkers will know why there is a Francis Lewis Boulevard in Queens. YES

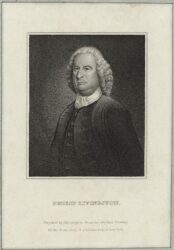

•Philip Livingston (New York) The 60-year-old member of one of New York’s wealthiest families, with an estate of 160,000 acres on the Hudson River, he was a merchant who favored the patriot cause. But like many New Yorkers, he was more moderate and cautious about declaring independence and was absent when the entire New York delegation abstained from the vote. He signed in August. (Robert Livingston, a cousin and member of the Declaration draft committee, was also absent from the vote and never signed the Declaration).

Philip Livingston (New York Public Library) https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-24a4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

“General Washington and his officers met at Philip’s residence in Brooklyn Heights after their defeat in the battle of Long Island, and decided to evacuate the island. The British subsequently used Philip’s Duke Street home as a barracks, and his Brooklyn Heights residence as a Royal Navy hospital. As the British occupied New York City, Philip and his family fled to Kingston, NY where he maintained another residence. Later, the British burned the city of Kingston to the ground as they did Robert R. Livingston’s mansion, Clermont, across the Hudson River.” (Source: Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Although he sold some of his property to support the war effort, his family continued to amass large land holdings in upstate New York. In poor health, he died at age 62 in 1778, when Congress was forced to evacuate Philadelphia and move to York, Pa. YES

•Thomas Lynch, Jr. (South Carolina) At 27, the second youngest signer (after Edward Rutledge also of South Carolina), he was born on one of the South’s major rice plantations. A lawyer, he was the son of a a wealthy rice planter, who suffered a stroke while a delegate in Philadephia. The younger Lynch was sent to Congress. (His father was unable to vote or sign.) Both left for home in poor health and the elder Lynch died en route.

During the debates after the adoption, Lynch was reported by John Adams to threaten secession:

If it is debated, whether their Slaves are their Property, there is an End of the Confederation. Our Slaves being our Property, why should they be taxed more than the Land, Sheep, Cattle, Horses, &c.

Source: John Adams diary 27, May – 10 September 1776 [electronic edition]. Adams Family Papers: An Electronic Archive. Massachusetts Historical Society.

Hopsewee Plantation (Photo credit Alan Sherlock via Historic Hopsewee)

Lynch Jr. and his wife later sailed for the West Indies in the hope of regaining his health but both died at sea in 1779 when their ship was lost in a storm. Among the youngest signers, he was the youngest signer to die at age 30. YES

Read more about slavery and the Founders in my book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.