(Revision of April 13, 2012 post)

“That these are our grievances which we have thus laid before his majesty, with that freedom of language and sentiment which becomes a free people claiming their rights, as derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate: …. (Kings) are the servants, not the proprietors of the people.”

–Thomas Jefferson, A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774)

Born on April 13, 1743 at Shadwell, his father’s estate in Albermarle County, Virginia, Thomas Jefferson embodied what I call the “Great Contradiction”–that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

Read my article on teaching the “American Contradiction” in Social Education.

Jefferson was the son of a planter and surveyor, Peter Jefferson and his wife, Jane Randolph Jefferson, who came from one of Virginia’s wealthiest families. Thomas Jefferson’s father had moved the family to the Tuckahoe plantation owned by William Randolph, which Peter Jefferson managed as executor.

The third child in a family of ten and oldest son, Thomas was a bookish boy who studied with a local clergyman and later at a school in Fredericksburg with Reverend James Maury who taught Jefferson the classics in their original languages. Thomas was fourteen when his father died, leaving the boy head of an estate with about 2,500 acres and thirty enslaved people.

The Declaration’s future author distinguished himself early as a scholar at the College of William and Mary, and gained admission to the Virginia bar in 1767. His literary prowess, demonstrated in A Summary View of the Rights of British America, prompted John Adams to put Jefferson forward as the man to write the Declaration, a task he accepted with reluctance.

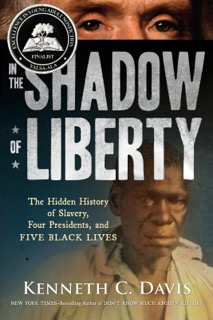

Most of the war years were spent in Virginia as a legislator and later as governor, a period of some controversy as he was criticized for failing to aggressively defend Virginia against British attacks. He barely escaped capture in Richmond in 1781, a story told in my book In the Shadow of Liberty.

After his wife’s death in 1783, he served as ambassador to France, where he could observe firsthand the French Revolution. It was here that Jefferson is believed to have begun his relationship with Sally Hemings, the enslaved 14-year-old thought to be half-sister of Jefferson’s dead wife, Martha.

Returning to America in 1789, Jefferson became Washington’s secretary of state and began to oppose what he saw as a too-powerful central government under the new Constitution, bringing him into a direct confrontation with his old colleague John Adams and, more dramatically, with Alexander Hamilton.

Running second to Adams in 1796, he became vice president, chafing at the largely ceremonial role. In 1800, Jefferson and fellow Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr tied in the Electoral College vote, and Jefferson took the presidency in a tense and controversial House vote that required more than 30 ballots.

While President, Jefferson engineered the Louisiana Purchase and wrote what may be his second most famous lines in a letter addressing religious freedom under the new American government.

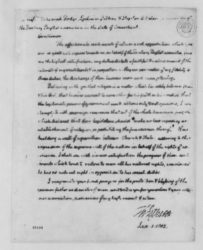

Jefferson to Danbury Baptists (Monticello)

i

“Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between man and his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legislative powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between church and State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties.”

–Thomas Jefferson

Letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, (January 1, 1802)

After two terms, he returned to his Monticello home to complete his final endeavor, building the University of Virginia. As he lay dying, Jefferson would ask what the date was, holding out, like John Adams, until July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration.

With the advantage of hindsight, cynicism about Thomas Jefferson is easy. But the baffling question remains: How could a man who embodied the idealism of the Enlightenment enslave Black people –and it is widely assumed — father children by one of them? What do we do about Thomas Jefferson?

There is no satisfying answer. Earlier in his life, he had unsuccessfully argued against aspects of slavery. At worst, Jefferson may not have thought of slaves as men, not an unusual notion in his time. And he was a man of his times. He was completely dependent upon slavery for his financial life and the political power of his southern slave-holding class. Like other men, great and small, he was not perfect.

Jefferson’s life, writings, and politics are discussed in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents from which this material is adapted.

His relationship with the enslaved people of Monticello is explored in detail in my book In the Shadow of Liberty.